All or nothing: While today Superman only concentrates on the really big goals, in the 1970s he was on occasion still busy rescuing kittens from trees. Such feats can be experienced at the SCHIRN’s open-air cinema on August 16.

Dramatic scenes on the remote planet Krypton: Jor-El pleads with the ruling body, the Science Council, to evacuate the planet. Given the ruthless exploitation of natural resources Jor-El is convinced that a catastrophe of immense proportions is imminent, namely the planet’s explosion. At the same time General Zod attempts a military coup in order to blast away the ruling class. This is followed by a dizzying pursuit, and finally Jor-El throws his young infant into a space capsule that speeds on its way to Earth. He at least wants his son Ka-El to survive, and later on the blue planet he will be given the name Clark Kent. But Jor-El does not escape, and the planet explodes.

Film Poster of 1978, Image via verdoux.wordpress.com

This fast and furious opening scene comes from Zack Synder’s 2013 remake of the Superman movie called “Man of Steel”, and the content at least is largely identical with that of Richard Donner’s classic “Superman” from 1978. What is interesting is how the two versions differ in terms of the general setting since superhero stories tend to describe the times when they were made.

A cold, technical planet

Snyder’s Krypton recalls the world in “The Lord of the Rings” trilogy: mountainous landscapes, flying dragons and other primeval creatures, and even the costumes reflect medieval garments – except that the Kryptonians have technology we are still a long way from acquiring. For instance, there are flying artificial intelligences apparently made of organic material that communicate as equals with their creators.

Planet Krypton, Image via ew.com

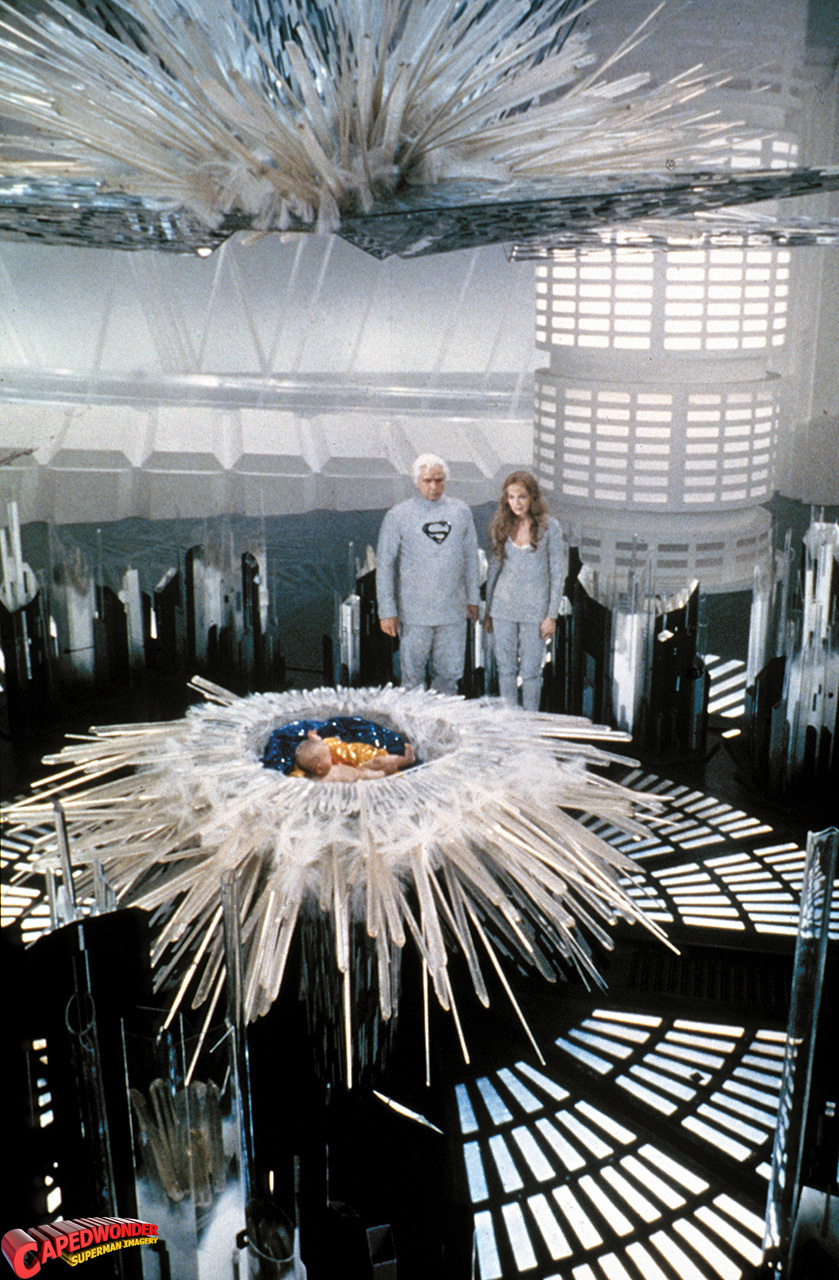

The situation is totally different with Richard Donner’s Krypton: A cold, technical planet without its own atmosphere, like Death Star in Star Wars. Apart from the inhabitants there is not an awful lot there, Donner films a strong contrast between glaring light and eternal blackness. There are no action-packed sequences as in “Man of Steel”, instead, Marlon Brando as Jor-El holds long monologs about responsibility and humanity.

Superheroes in B-movies

Some people might consider Superman to be the most boring of all superheroes, but it cannot be denied that he is the first. Moreover, Richard Donner’s Superman film from 1978 is more or less the first superhero blockbuster, which in its way anticipated the Marvel Cinematic Universe and all those superhero stories that dominate movie theaters today. Previously, superheroes were seen exclusively in B-movies or TV series, located on the divide between family entertainment and trash. “Superman” was happy to bring that to the big stage, and the special effects showcase the very best of what was technically available at the time.

Superman. The Movie, 1978, Image via wallpaperstock.net

The figure of Superman himself was always a child of his time. Launched in 1933 by his creators Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster as a baldheaded villain in in the magazine “Science Fiction” they published themselves, from 1934 the team of authors altered the figure into a superhero, but one who was only to be seen regularly in comics from 1938 onwards and proved to be highly popular. The “Superman” of those years was a very uncouth figure, who lashed out with great violence at gangsters, profiteers, or men that physically abused women.

Beating the hell out of Hitler

At this time, Superman was still at loggerheads with the Federal cops, and stands up for the socially deprived. In one episode of the comic, our keen superhero destroys a completely desolate, low-income housing project to ensure its residents are rehomed in new, better apartments. In the 1940s, Superman became a whole lot softer and friendlier, he no longer kills, he co-operates with local authorities, and he beats the hell out of Hitler, Stalin and the Japanese Emperor Hirohito – hardly surprisingly, he became a favorite amongst the soldiers fighting in Europe.

In “Man of Steel” it is clear from the start that humanity’s existence is at stake. Clark Kent, alias Superman, has to decide between his origins and his new world, between ethnic origin and self-chosen new territory. In the classic version no single minute is as serious and weighty as in the re-make. True, in the former Lex Luther, a classic villain (who verges on slapstick) played by Gene Hackman - also threatens the lives of dozens of people with his dark dealings and Superman has to hold the world together in the truest sense of the word, but at no point do things ever appear so threatening that ultimately evil could gain the upper hand. Superman has the situation under control and even has time to rescue a cat stuck up a tree. Naturally, in today’s world the man of steel has no time at all for such trivialities; it is about all or nothing.

Superman and the Trinity

What both films do have in common are basic Christian topics: Superman is sent to the world by his parents to save humanity and make the Earth a better place. In Richard Donner’s “Superman” parallels are even drawn to the Trinity: For example, Jor-El tells his son that they will always be one, and that the one will see the life of the other through their eyes. “The son will become the father and the father will become the son”. In “Man of Steel” Superman is prepared to sacrifice his life for humanity and shortly before sending his son to Earth the father says to his wife: he will be like a god for them.

Gene Hackman playing the villain in Superman. The Movie of 1978, Image via pinterest.de

The analogies in “Man of Steel” even went so far that on its own dedicated website the production studio Warner Bros. pointed out that Jesus Christ was the very first superhero. Similarly, Jewish elements can be discovered in the figure; in Nazi Germany Propaganda Minister Goebbels justified the banning of the comic with the sentence “Superman is a Jew”.

Peter Saul, Superman and maximum exaggeration

Simultaneously, Superman is naturally a prototypical American figure, who talks of immigration and exceptionalism, conforming and being chosen. Peter Saul often takes on this deeply American “Pop archetype” as Dietmar Dath called it, when for example in “Superman & Superdog in Jail” he shows he superhero as an overblown figure in a cell or has him executed in “Superman in the electric chair”. Saul says he wanted to “grossly exaggerate” with his pictures; ultimately in this exaggeration he is availing himself of the same principle as the Superman stories. Peter Saul’s exaggeration veers into the grotesque, but basically takes the same line as all superhero stories: It aims to address the standards society sets itself and the reality of the day, and reflect them in the domain of the fantastic or rather with “maximum exaggeration”.

At the mercy of waiting

Artist Bani Abidi is dedicated to the dark absurdities of everyday life. In her video work "The Distance from Here" bureaucracy takes over and waiting...

“Please don’t make a film about Godard!”

A film about filmmaking sounds a bit meta. But Kristina Kilian’s video work takes us on a ghostly journey through Godard’s Germany after the fall of...

Black is not a Color

In a film series, Oliver Hardt combines the themes from Kara Walker’s work with the perspectives of Black people in Germany. In conversation with...

How do we Remember?

In which places does history become visible? And what do we remember at all? Maya Schweizer begins her search for clues in the sewers and slowly feels...

Film highlights from South and North America

How can we break with the power relations of the past and create a decolonial future? A look at the representation of Indigenous women in film.

Must See: The World of Gilbert & George

Eccentric, fascinating, repulsive, entertaining and full of symbols: “The World of Gilbert & George” is a collage about the artifice of everyday life...

Spring is coming, and so is Magnetic North

For the first time in Germany, principal works from Canada’s major collections are on view at the SCHIRN. At the same time, the exhibition examines...

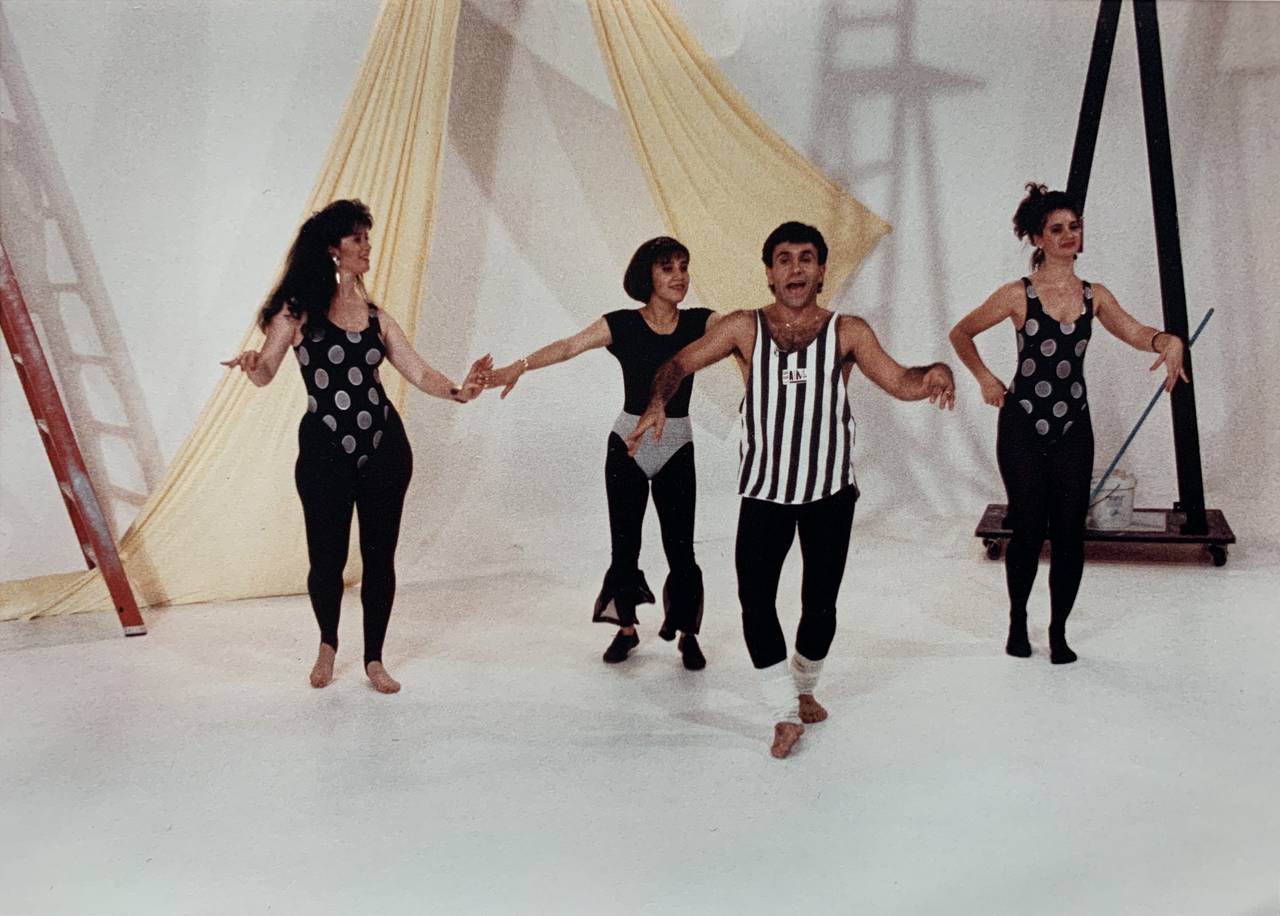

A Revolution in Iranian Dance

After the Iranian Revolution a nationwide dance ban was issued. It was subverted by smuggled video cassettes of dancer-in-exile Mohammad Khordadian,...

How to perform painting

This is perhaps the best way to describe the work of video artist Angel Vergara: Art history meets pop culture, the artist himself appears as a...

About the resistance of our bodies

Hypnotic dances and hybrid beings in cyberspace: Video artist Johanna Bruckner transforms the human body into digital matter.

More than a Honeypot

Young, beautiful and dangerous: the prototype of the Bond Girl still shapes the cliché of spies. Author Chloé Aeberhardt on the reality of espionage...

How to create the unexpected

About life in exile, anarchic art, and the “black milk” of the earth: The art historian Media Farzin met her old friends Ramin and Rokni Haerizadeh...