How Torrey Peters’ much-discussed book “Detransition, Baby” can bridge the gap between underground and mainstream, and why it matters.

With her first novel, “Detransition, Baby”, recently published by Penguin Random House, Torrey Peters has established herself as an important voice in the burgeoning field of transgender literature. Over the last decade, trans and non-binary writers have turned their attention away from memoir and theory and towards fiction, and “Detransition, Baby” – about a love triangle between two trans women, one of whom has detransitioned, and a divorced cisgender woman, has become one of the first novels by a trans woman to appear on one of the “big five” US publishing houses.

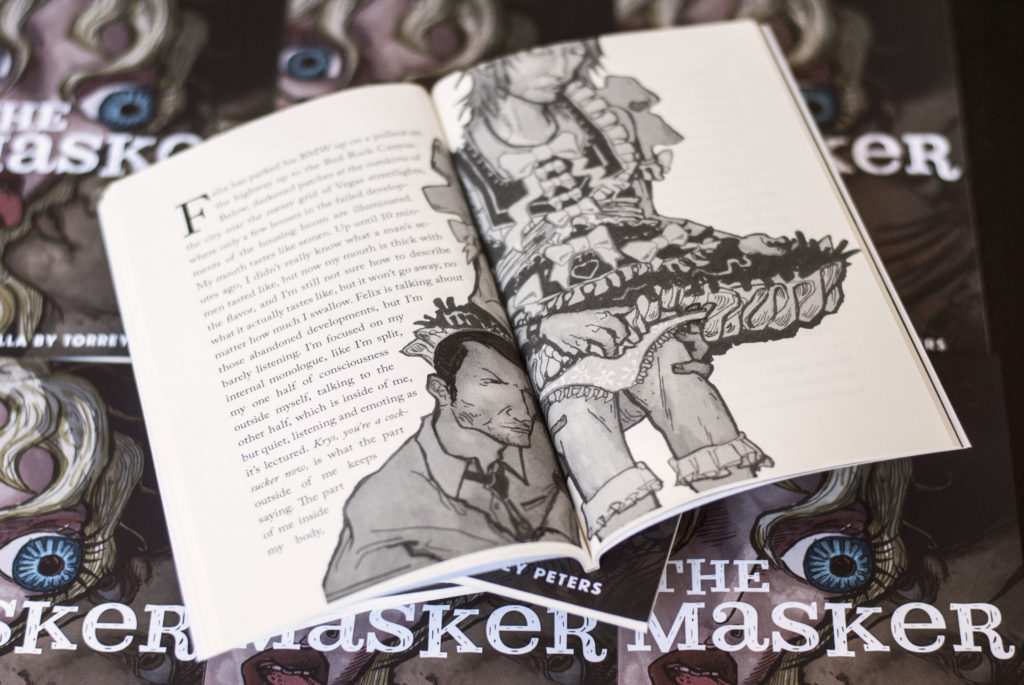

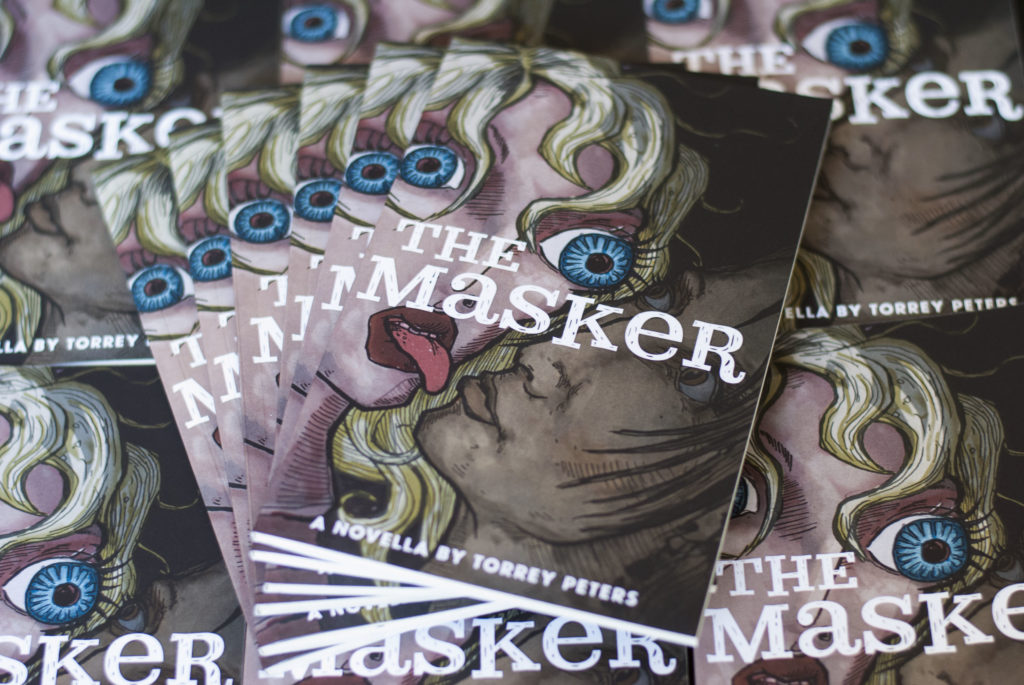

Peters’ success raises interesting questions about who these novels are for, the uses of writing for a minority community, and of aiming for a wider audience. In the preface to her first work -a self-published novella called “The Masker” (2016) – Peters expressed her excitement to see her work “as part of a conversation with … people like me”.

Peters’ success raises questions about who these novels are for

“The Masker” was illustrated by artist Sybil Lamb, because, wrote Peters, Lamb’s novels and zines helped her to see what becomes possible “when trans women write for trans women, rather than a larger commercial market”. “Detransition, Baby”, however, is dedicated to divorced cisgender women, who, said Peters, “must start over at a point in adulthood when they’re supposed to be established”, much like trans women.

Torrey Peters, PHOTO: COURTESY OF NATASHA GORNIK, Image via http://www.torreypeters.com/about/

An intelligent, funny and highly relatable work, “Detransition, Baby” has become a crossover hit, being optioned for a TV series and longlisted for the Women’s Prize for Fiction in the UK.

Peters’ success, coming soon after Andrea Lawlor’s “Paul Takes the Form of a Mortal Girl” was picked up by Vintage from small LGBT+ publisher Rescue Press in 2019, tells us plenty about the current place of trans and non-binary literature. It confirms North America, and especially the US, as its creative hub, as it has been since the 1990s. There, trans novelists and poets benefit from a well-developed infrastructure of small presses that allows them to flesh out their ideas within a community of trans readers, providing a platform to take their work to mainstream publishers if they wish.

Torrey Peters, The Masker, Image via www.torreypeters.com

Whether they do this depends more on their chosen genre and prose style than their choice of characters or themes: the skill of fiction and poetry has always laid in its authors’ ability to convey highly particular experiences to a readership that has not known them, as well as in making them resonate with those who have. In Detransition, Baby, Peters expertly bridges the gender gap by combining experiences unique to trans women with insights into how being trans complicates more universal ones, around employment, family and relationships, making brilliant use of self-deprecating humour to disarm potentially hostile audiences, be they cis or trans.

Peters brilliantly uses humour to disarm potentially hostile audiences

Peters has always been vocal in acknowledging writers who paved the way for her, recognising that while we don’t need specifically trans influences to create believable characters, construct compelling storylines or innovate with form, our predecessors have opened up possibilities. The earliest trans authors published memoirs, aiming to provide a more sympathetic account of their experiences than those in sensationalist news stories.

In the 1990s, trans theory grew out of critiques of those memoirs, which, the theorists argued, had not been truthful about what cross-gender living actually entailed for fear of enflaming anti-trans prejudices. As well as striving towards a political definition of “trans” that could include as many people as possible, and publishing histories of this community, they tried to create “a transgendered writing style”, as Gender Outlaw author Kate Bornstein put it, often merging autobiography, cultural criticism and fiction in texts aimed primarily at trans readers and published by underground presses.

Throughout the 2010s, the novel has emerged as the form that can transcend this divide, from Imogen Binnie’s acclaimed road-trip narrative “Nevada” (Topside, 2013) to Jordy Rosenberg’s speculative history of an 18th century proto-man, “Confessions of the Fox” (Penguin Random House, 2018). Making this jump has brought new challenges: the demand for honesty made by the theorists, and the public, has led trans critics to worry about the political efficacy of writing, as Peters described her novellas, about “the ways in which trans women are fucked up and flawed” amidst a global effort to decrease trans visibility that has stretched from Putin’s Russia to Trump’s USA via Bolsonaro’s Brazil and Boris Johnson’s Britain, which has a small but vocal, well-connected cult of transphobic feminism.

[...] the ways in which trans women are fucked up and flawed.

Imogen Binnie, Nevada (Detailansicht), Image via boredangry.tumblr.com

There, in response to “Detransition, Baby” being longlisted for the Women’s Prize, the “Wild Women Swimming Club” published a letter condemning Peters’ nomination, which they said “communicates powerfully that women authors are unworthy of our own prize, and that it is fine to allow male people to appropriate our honours”. The Prize responded by recognising Peters’ gender and disavowing the letter, which was signed pseudonymously by various dead female writers – an absurdity that points back to the tactic of writing honestly about our lives in the face of such hostility.

As Peters puts it in “The Masker”, a story of what happens when a cross-dresser tries to live out pornographic fantasies of forced feminisation, dedicated to “my former self at my most afraid”, there’s “a kind of safety” in being open about our deepest desires and secrets: protagonist Krys asserts that calling her “a faggot or perv” when she wears a sissy maid outfit is “just redundant”. By now, it’s clear that trying to placate transphobes is pointless: honesty like Peters’ will give more confidence to younger trans writers – as well as artists, filmmakers, musicians and other creative people – and sooner or later, we’ll reach the point where they can’t shout us all down or shut us all out.

[S]ooner or later, we’ll reach the point where they can’t shout us all down or shut us all out.

Torrey Peters, The Masker, Image via www.torreypeters.com

#PRIDEMONTH

June is #PRIDEMONTH: The month exemplifies the society we want to live in and demand all year round. That means LGBTQIA+ rights, queer visibility and acceptance. We take this as an opportunity to focus on current debates and positions of the queer community on SCHIRN MAG.