At the end of the 1990s the French critic Nicolas Bourriaud coined the term “relational aesthetic” for a new art trend that put interpersonal encounter at its core.

When live rats are fed Italian cheese in order to subsequently be sold as artworks in limited edition (Maurizio Cattelan), when female artists give aerobics classes in the gallery space (Christine Hill) and collectors purchase the ingredients for a Thai curry (Rirkrit Tiravanija), then it becomes clear: The conceptualities by which art has been deciphered and analyzed thus far no longer apply. How can we describe the material, the form, the aesthetic of works that generally take place as fleeting encounters or temporary, interactive situations? This was the question addressed by the French curator and critic Nicolas Bourriaud in his essay collection “Relational Aesthetics” (1998/2002).

Rirkrit Tiravanija, Pad thai, Image via onarto.com

His theory: In the 1990s there was a surplus of communication and consumption and even the area of social interaction – relationships, conversations, encounters – is now barely experienced as such, but rather begins to blur into a spectacular representation of itself in the Debordian [Guy Debord, French author and filmmaker, d.1994] sense. In these days of constant, compulsive Instagram staging, this claim appears all the more comprehensible. Bourriaud talks about a “society of extras”.

Room for inter-human relations

He therefore refers to the “relational artworks” that develop in this time as “hands-on utopias” – because they no longer form imaginary, utopian, symbolic realities, but rather describe actual ways of life and actions that play out in reality and offer a social intermediate space whose (temporal) structure contrasts with the daily routine, marked as it is by productivity and purpose, and instead leaves space for interpersonal communication.

Alix Lambert, Marriage Project, exhibition view "Mind-bending with the Mundane," at ICA/MECA, Image via adrianeherman.com

“The artist dwells in the circumstances the present offers him, so as to turn the setting of his life (his links with the physical and conceptual world) into a lasting world.” Artists make reference to the conditions of the present that each of them lives. It’s about collaborations, conviviality, contacts and agreements – between artists and gallerists, between artists and collectors, between individuals unknown to each other, between museum visitors, passers-by and supermarket customers.

Artwork as apparatus

What needs to be fundamentally reconsidered here is the form, the material: Here Bourriaud borrows Louis Althusser’s [French philosopher, d.1990] concept of a “materialism of encounters”, which does not stem from a previous availability, but rather understands forms as the result of an arbitrary encounter of elements. Hence an artwork can be perceived as an apparatus which, with a certain degree of arbitrariness, brings about those encounters.

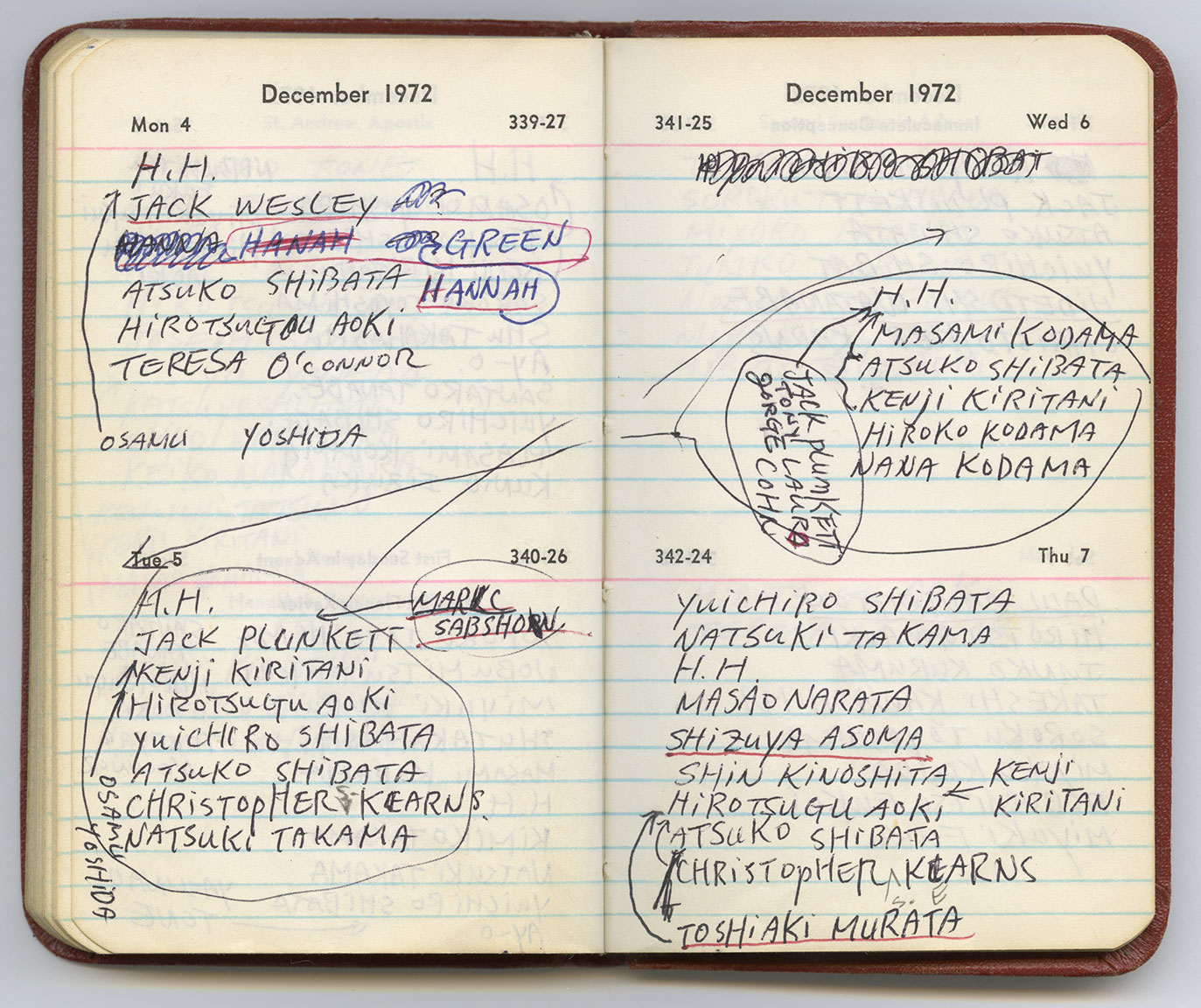

On KAwara, I Met, Image via guggenheim.org

On Kawara’s series “I met” consists of notebooks in which he wrote the name of the people he had conversed with every day in chronological order between 1968 and 1979. The twelve books comprise a total of 4,790 pages. Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster materialized the childhood memories of her gallerist Esther Schipper in the installation “The Daughter of a Taoist” (1992). In the same year Alix Lambert created the project “Wedding Piece”, spanning a period of six months in which she had four weddings and got divorced again just as quickly. Philippe Parreno invited people, on May 1, Labor Day, to carry out their favorite hobbies – albeit on a factory production line. Art as a constant state of encounter.

Creating worlds

“Peace appears not as an object, but rather as a process of interaction and communication”, it states in the announcement of the PEACE exhibition. Participating artists such as Lee Mingwei, Surasi Kusolwong and Isabel Lewis incorporate the exhibition visitors into their works, making them an essential component. In the tradition of the relational aesthetic, time and again they evoke a clash of different things, individuals and moods. And if these encounters last, then perhaps they will even create worlds. After all, as Bourriaud says: “In order to create a world, this encounter must be a lasting one.”

INTERVIEW. ISABEL LEWIS

The film to the exhibition: CAROL RAMA. A REBEL OF MODERNITY

Radical, inventive, modern: The film accompanying the major retrospective at the SCHIRN provides insights into CAROL RAMA's work.

Soon at the SCHIRN: Hans Haacke. Retrospective

A legend of institutional critique, an advocate of democracy, and an artist’s artist: the SCHIRN presents the groundbreaking work of the compelling...

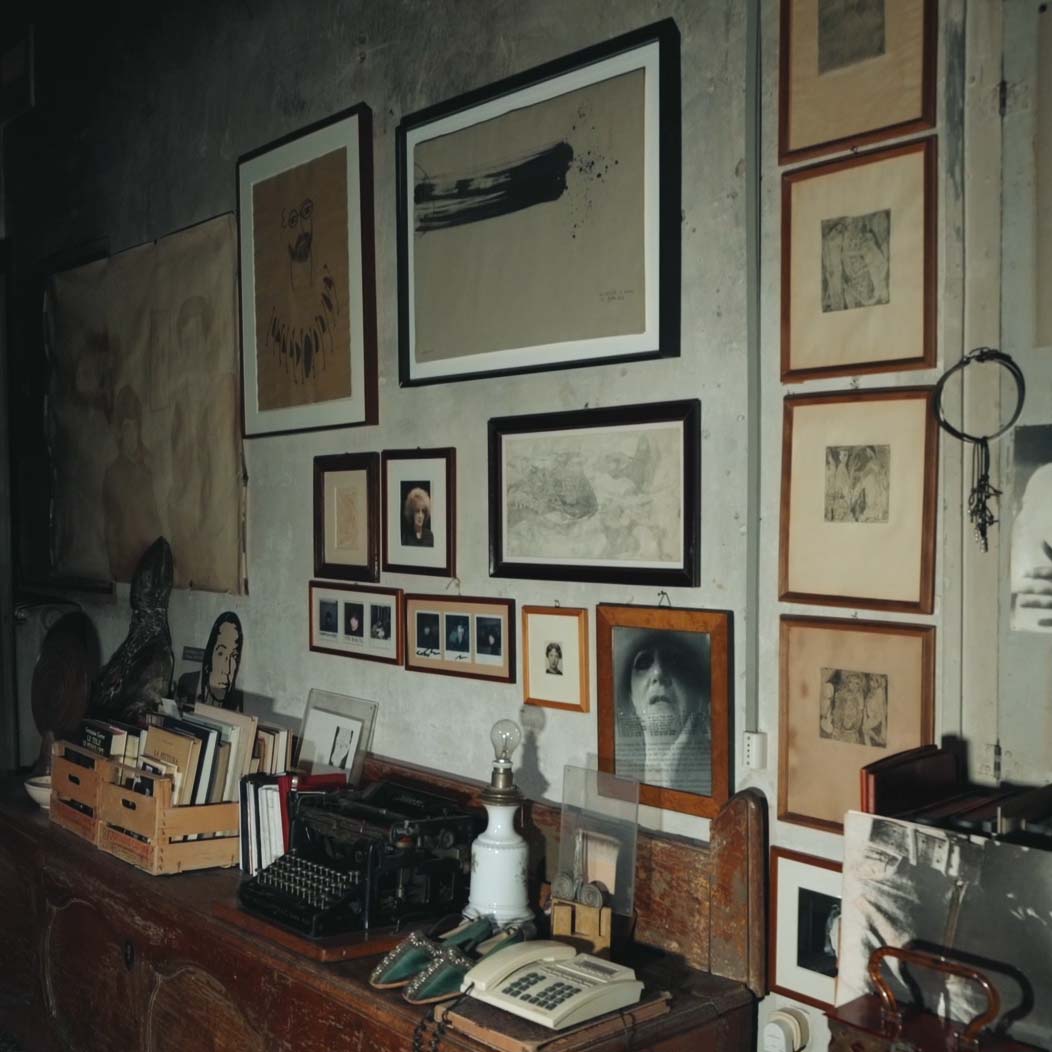

Carol Rama’s Studio: A nucleus of creativity

CAROL RAMA determinedly forged her own path through the art world. Her spectacularly staged studio in Turin was opened to the public only a few years...

PANEL: POLITICAL ACTIVISM BY SELMA SELMAN

Hosted by Arnisa Zeqo, Amila Ramović and Zippora Elders speak with the artist Selma Selman about her artistic career, the exhibition SELMA SELMAN....

Now at the SCHIRN: Carol Rama. A rebel of Modernity

Radical, inventive, modern: the SCHIRN is presenting a major survey exhibition of CAROL RAMA’s work for the first time in Germany.

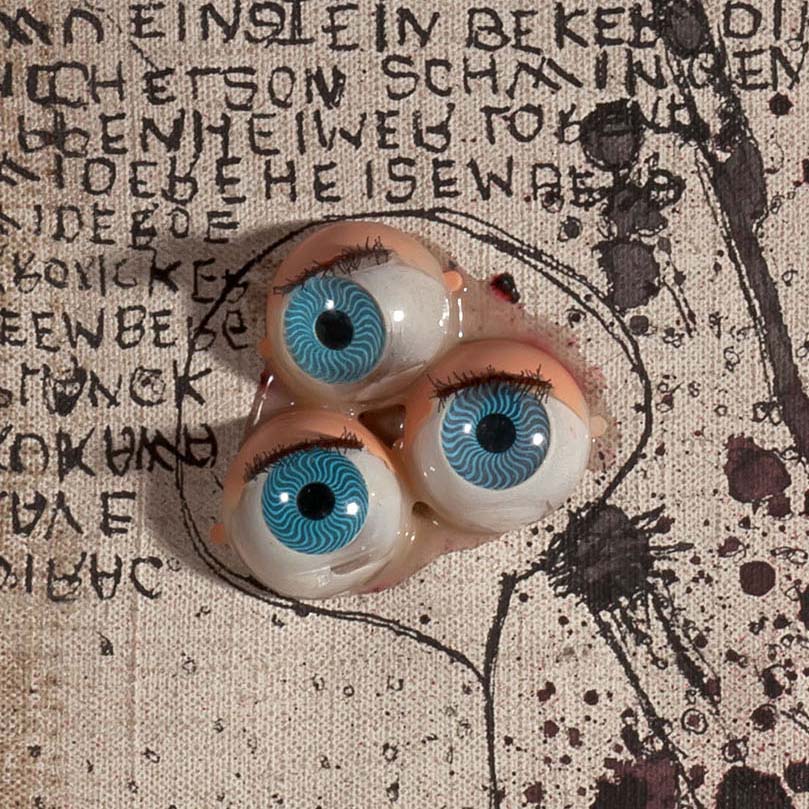

Carol Rama in 10 (F)Acts

CAROL RAMA was one of the most provocative female artists of the 20th century. With her explicit depictions of sexuality, physicality, and tabooed...

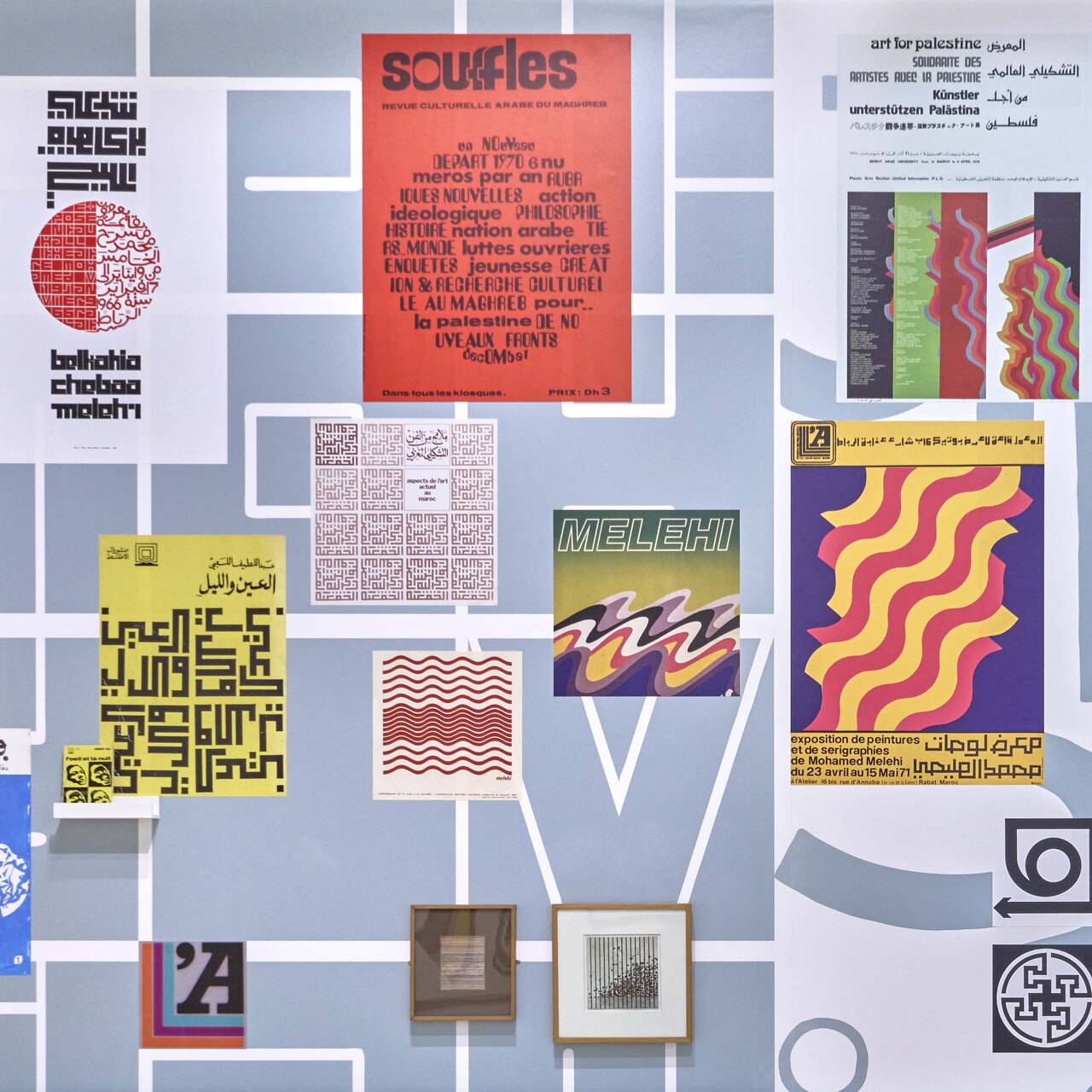

A lab for art in the public realm

The CASABLANCA ART SCHOOL wanted to make art part of urban life, visible for all, and interacting with the everyday culture of the city. To this day,...

Art and the world of journals in the Arab 20th century

Many of the teaching staff at the Casablanca Art School contributed to the journal “Souffles”, an extraordinary example for the strong...

A question of listening

Selma Selman creates her poetry of the future from multiple generations of Roma heritage completed with her subjective family story and history from...

5 questions for Salma Lahlou

Salma Lahlou is an independent curator. Her exhibitions and research projects continuously engage with the CASABLANCA ART SCHOOL. We spoke with her...

ABOUT TIME. With Alfred Ullrich

The artist Alfred Ullrich has spent a sufficient number of decades in the art world and engaging with it to know that attributions can always change....

CURATORIAL TALK: CASABLANCA ART SCHOOL

The curators, Madeleine de Colnet and Morad Montazami, talk to SCHIRN curator Esther Schlicht and filmmaker Mujah Maraini-Melehi about the background...