from October 30, 2015 to February 7, 2016 at the SCHIRN

The new century gets off to a stormy start

It is 1910. Artists and intellectuals are rebelling against the confines of the encrusted Wilhelmine period with radical innovations. Particularly in Berlin, new ideas are bubbling under the surface.

1910

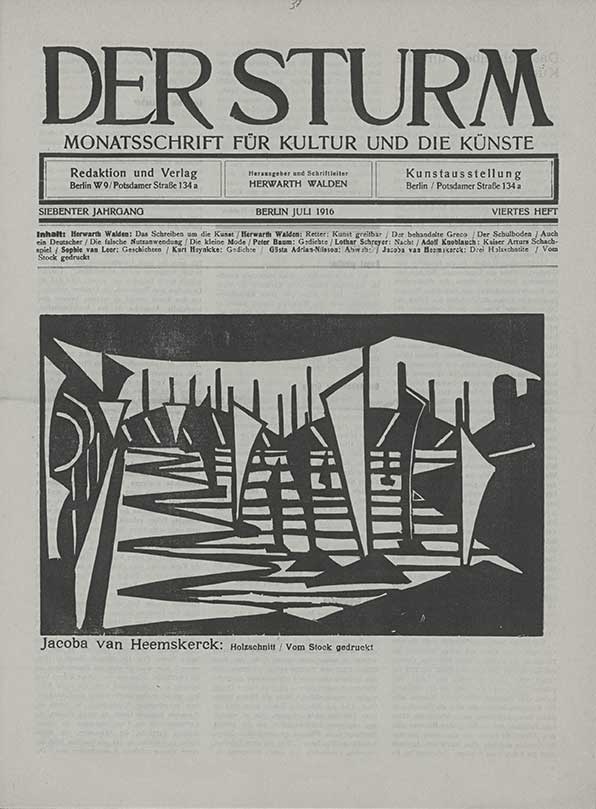

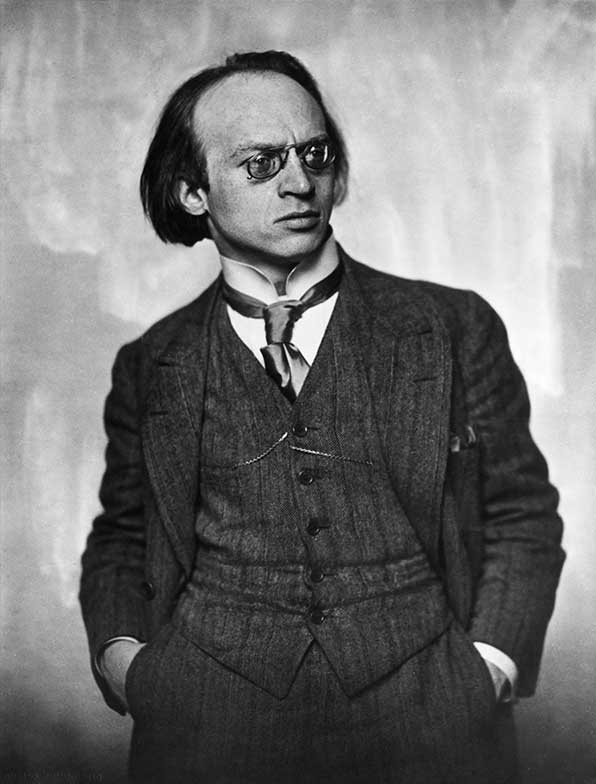

The atmosphere was highly charged. Art critic and composer Herwarth Walden took the bold step of founding a magazine to foster Expressionist art: DER STURM (THE STORM). It hit a nerve and quickly became one of the most important publications for interaction between writers and artists in Germany. The magazine’s great success led Walden to open the STURM Gallery, which was to make him a champion of avant-garde art.

THE STURM UNIVERSE

The great patron of the female avant-garde

The term STURM or storm was a battle-cry leveled at anything established. Walden called for the traditional art and culture of the period to be entirely renewed.

The STURM Gallery exhibited numerous international women artists, for example Scandinavian Sigrid Hjertén and Belgian Marthe Donas. Jacoba van Heemskerk from The Hague advanced to become the STURM woman artist per se – no other woman had more works exhibited in Walden’s gallery. From 1912 to 1932 Herwarth Walden organized at least 192 exhibitions in Germany and more than 170 abroad, including in New York and Tokyo.

WALD

EN

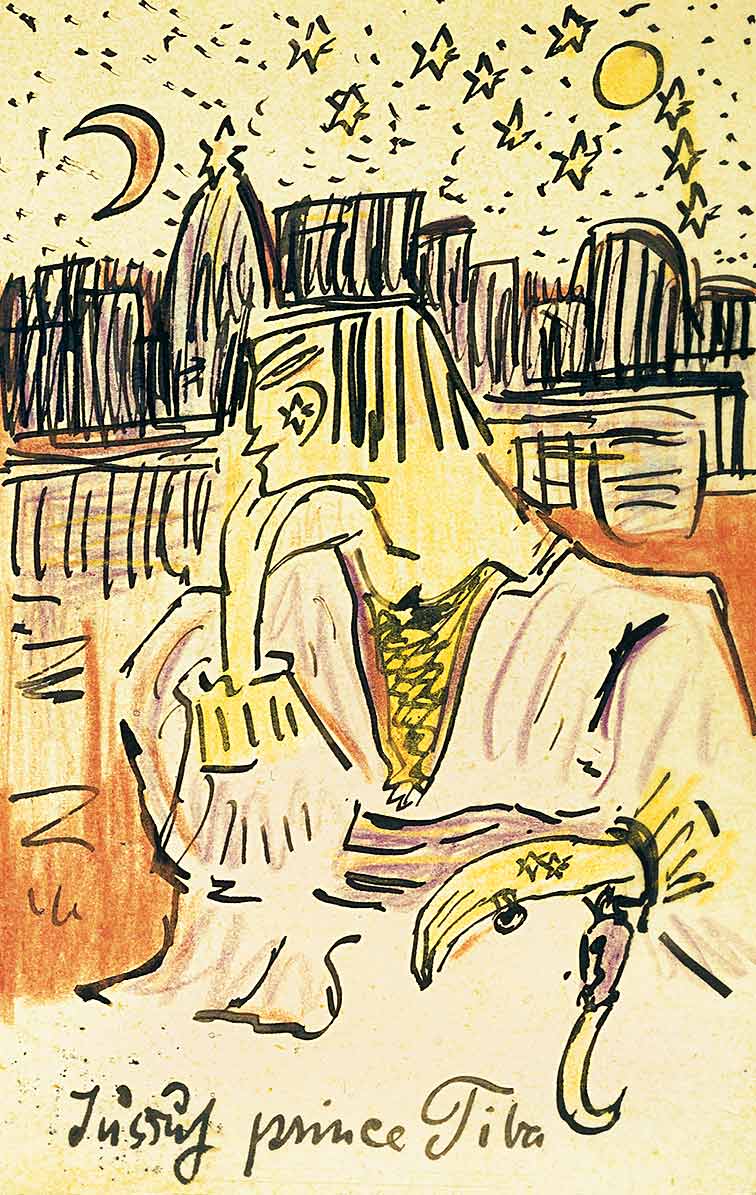

Else Lasker-Schüler

My husband is the greatest artist and most profound idealist I have ever encountered.

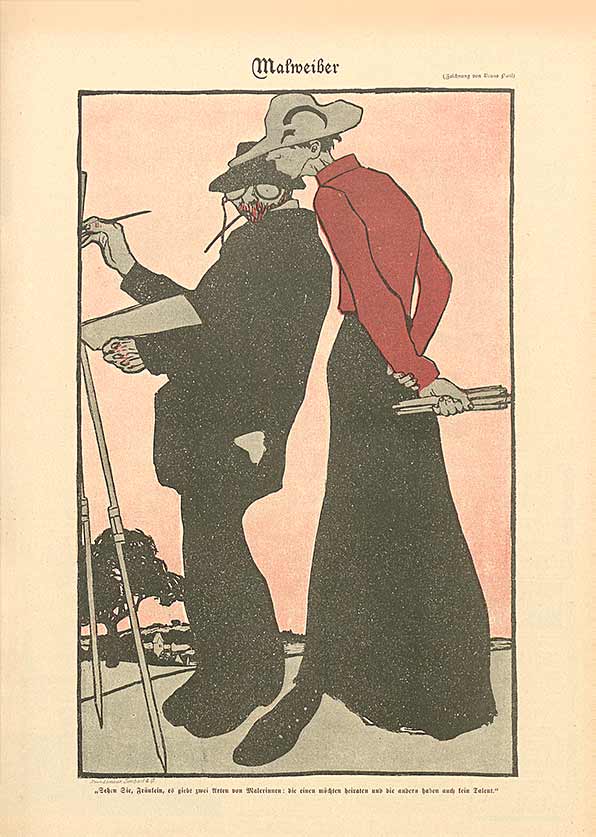

In the early 20th century it was widely believed that women lacked creative talent and consequently could never develop into artists who should be taken seriously.

„You see, my dear lady, there are two sorts of women painters, the first would like to marry and the others have no talent either.“

Simplicissimus, 1901

Against everything lukewarm and fearful

A vibrant capital

Capital of the German Empire, Europe’s largest trading hub, growing global metropolis. Loud, bustling, hectic. Berlin was all this at once. It had more than two million inhabitants. This was where the world of the chic bourgeoisie and that of the impoverished underclasses met.

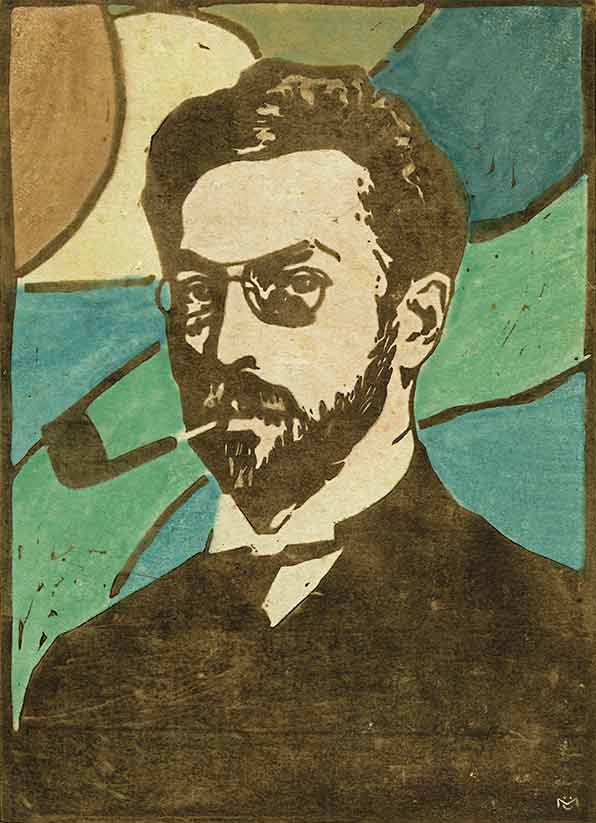

The driving force of STURM

The emergence of the entire STURM universe was largely the work of Herwarth Walden’s second wife, Nell Roslund, a native Swede.

ROS

LUND

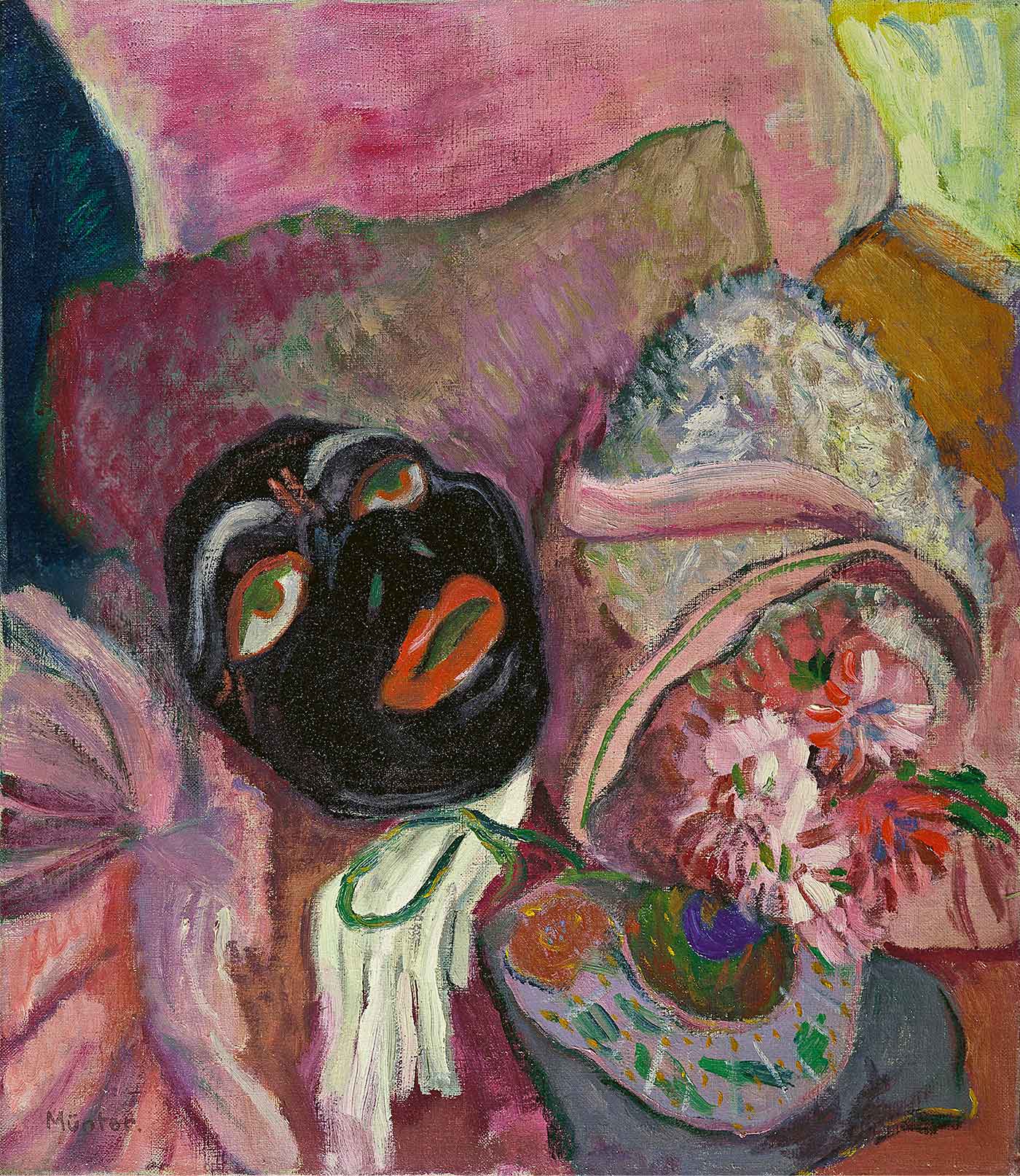

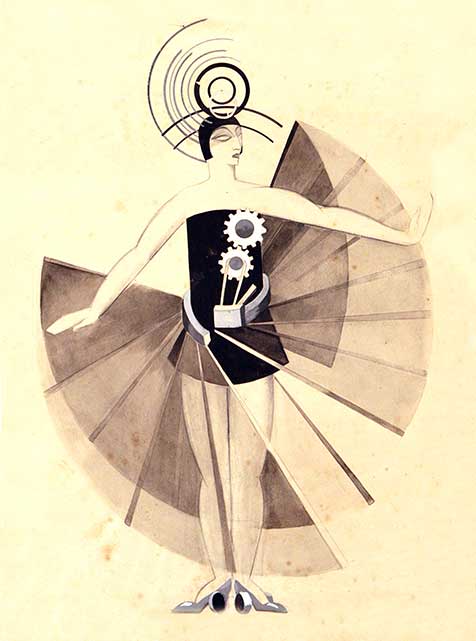

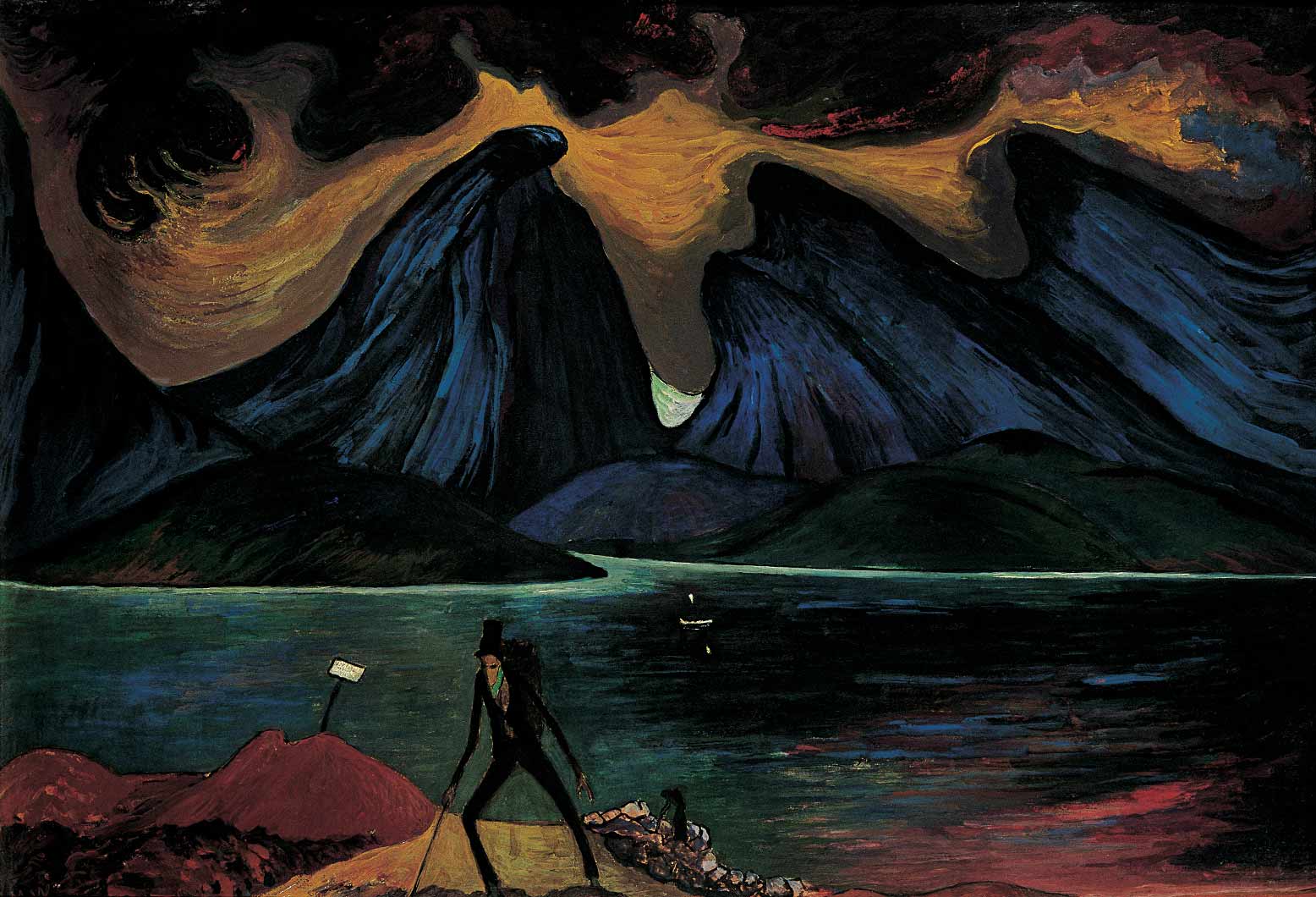

Bright swirls of color, stark contrasts and geometrical shapes define the stage design for the cloak-and-dagger comedy “The Phantom Lady”.

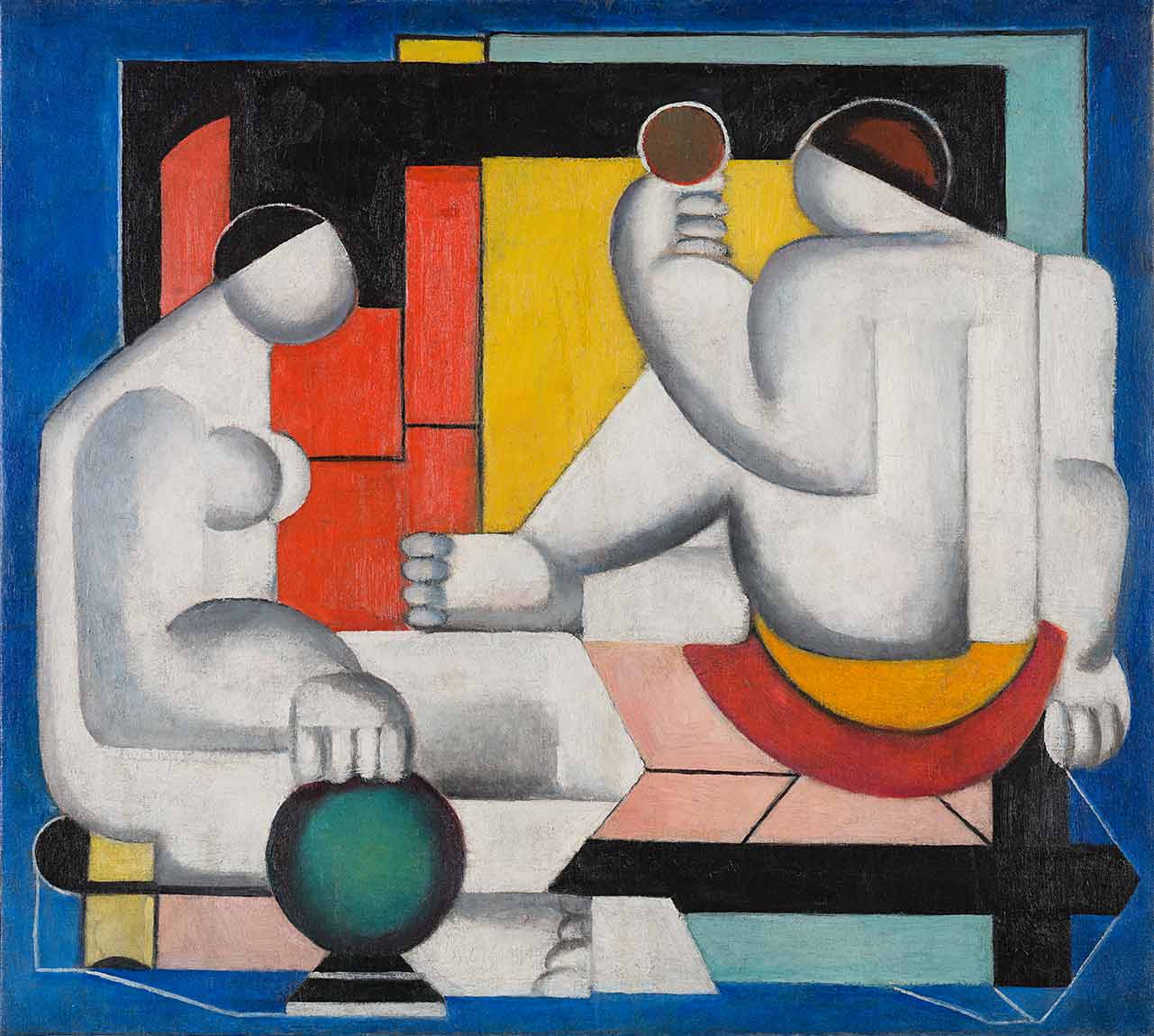

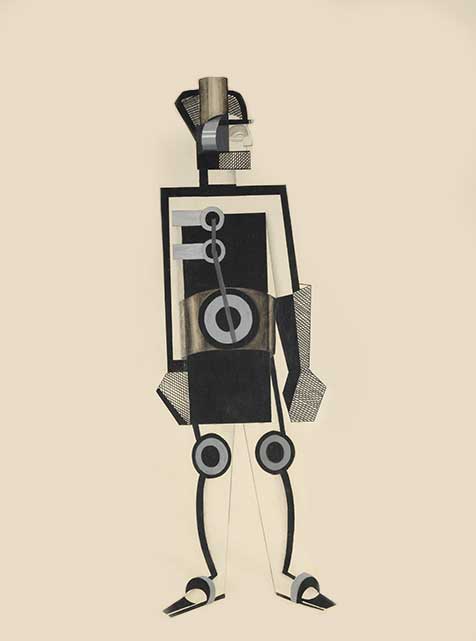

In the 1920s Walden was very interested in Eastern Europe and the radical political changes taking place there. Naturally, works by Vjera Biller from Belgrade or Russians Natalia Goncharova and Alexandra Exter were shown at STURM. Particularly Exter’s cool, techy-looking sets still appear futuristic today. With their unusual arrangement of spatial elements they play with viewers’ expectations.

In their native countries these women already numbered among the most pioneering of women artists. They were well ahead of their time and broke with established perceptual habits. Yet historiography rarely acknowledges the female contribution to the development of Modern art. Today many of their achievements are ascribed to their male colleagues, yet the latter often profited artistically from women artists.

STURM and the European avant-garde

World on the brink

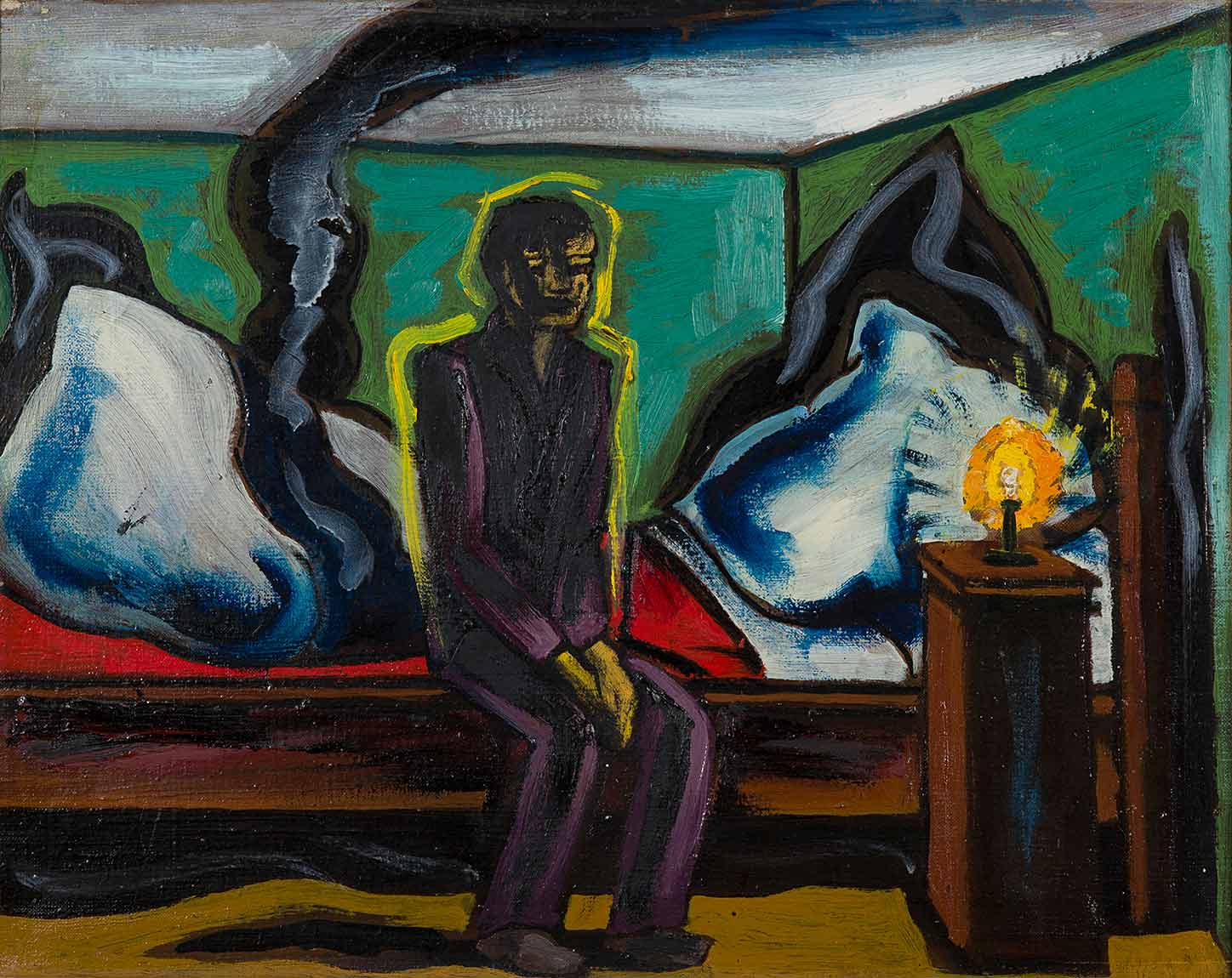

The monarchy had collapsed at the end of World War I, leaving chaos in its wake. The new republic was weak and lacked support amongst the population.

Rather than being able to tackle the problems created by the country’s defeat, the young democracy was caught up in a permanent battle for survival, having to defend itself against militant groups from both the extreme right and left. Owing to the bloody unrest in Berlin, the unpopular government convened in Weimar.

Between Apocalypse and ecstasy

EXCE

SSIVE

She paved the way for the Guggenheim Museum

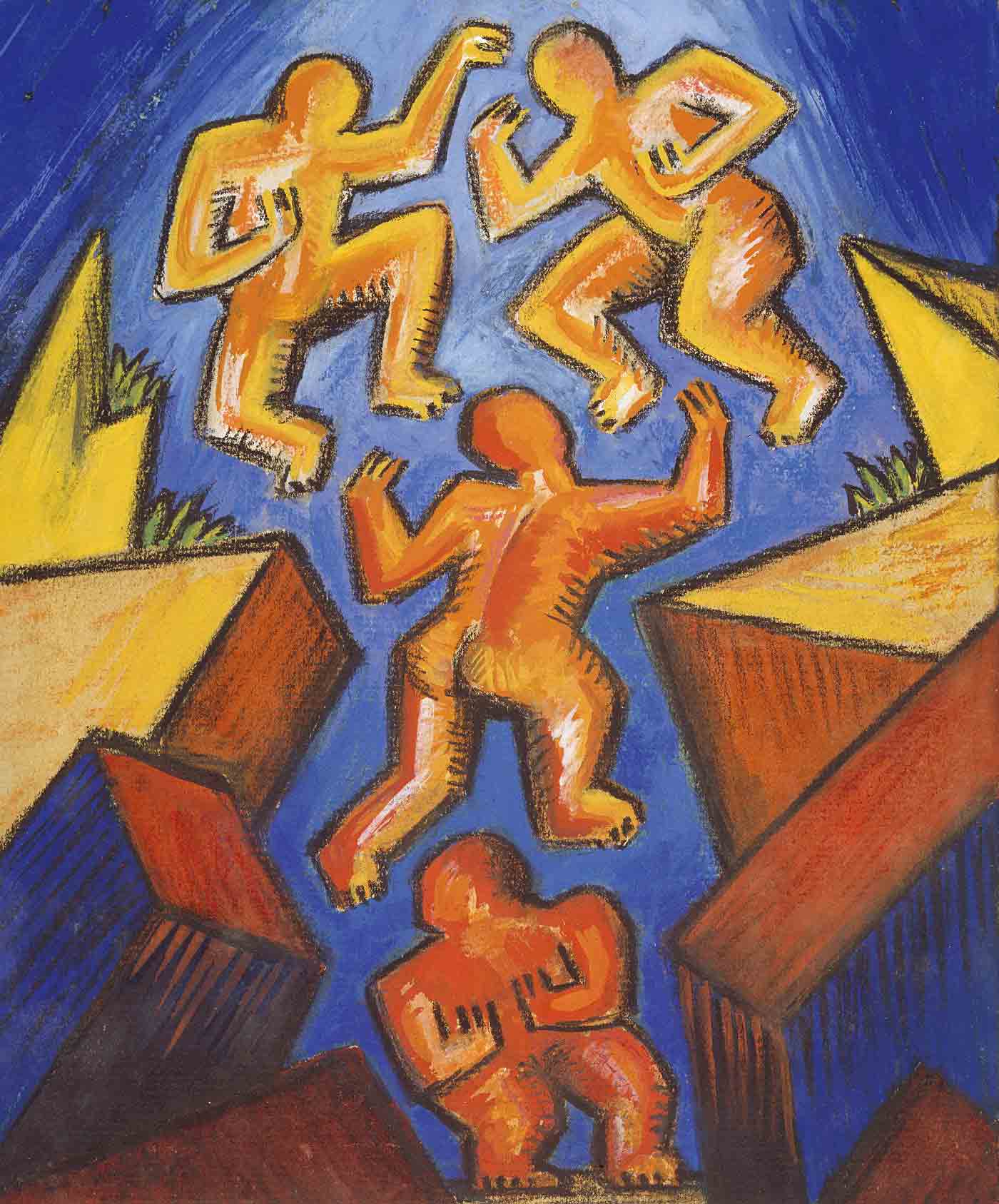

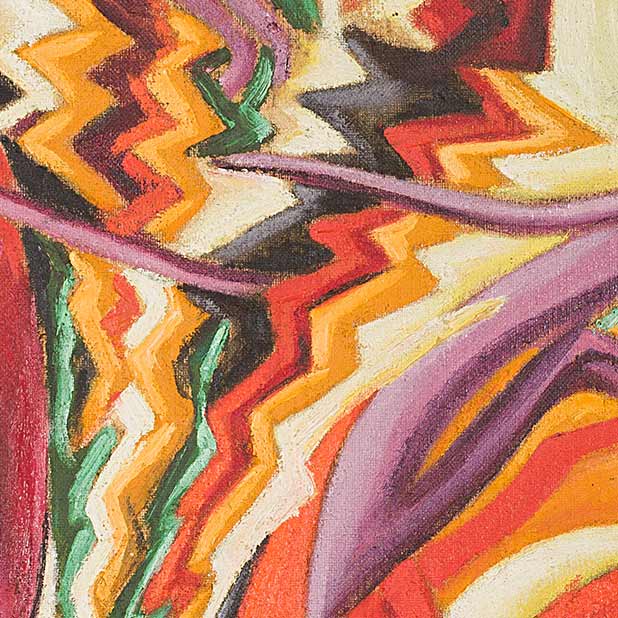

Red, green and blue contrasts in amorphous shapes overlap like sounds in the portrait-format painting. They stem from a fixed point in the lower left quarter of the image and extend out in a wild rhythm in all directions across the entire painting.

It was not only artistically that Rebay was a pioneer: In 1927, following the end of a relationship, she emigrated to America. There she met industrial magnate Solomon R. Guggenheim, whom she encouraged to collect contemporary European art. As long-standing advisor to Guggenheim, Rebay laid the foundations for the establishment of the famous Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, today one of the world’s most important collections. It was also Rebay who commissioned architect Frank Lloyd Wright to design the spectacular museum building.

The new woman

The age of diverse art trends

The years from the turn of the century until the Nazis seized power were a time of stylistic experimentation for artists. This development was fostered by alternative training options and the art market beyond the state academies. Several styles existed simultaneously, were deemed of equal merit, and developed alongside, out of, or by merging with one another. Naturally, women artists also distinguished themselves in these innovative styles, shrugging off the prejudice that women were not capable of pioneering artistic achievements. For Herwarth Walden all these new styles were “Expressionist”, in keeping with his world view, while art history today distinguishes more strongly between the various artistic positions.

AVANT

GARDE

Amazons of Modernity

The growing acceptance of female skills in various areas of life paved the way for female artists to also invade this hitherto male domain. Naturally, this was not without obstacles. It was considered ambivalent praise for women artists for their work to be described as “masculine” – naturally by men.

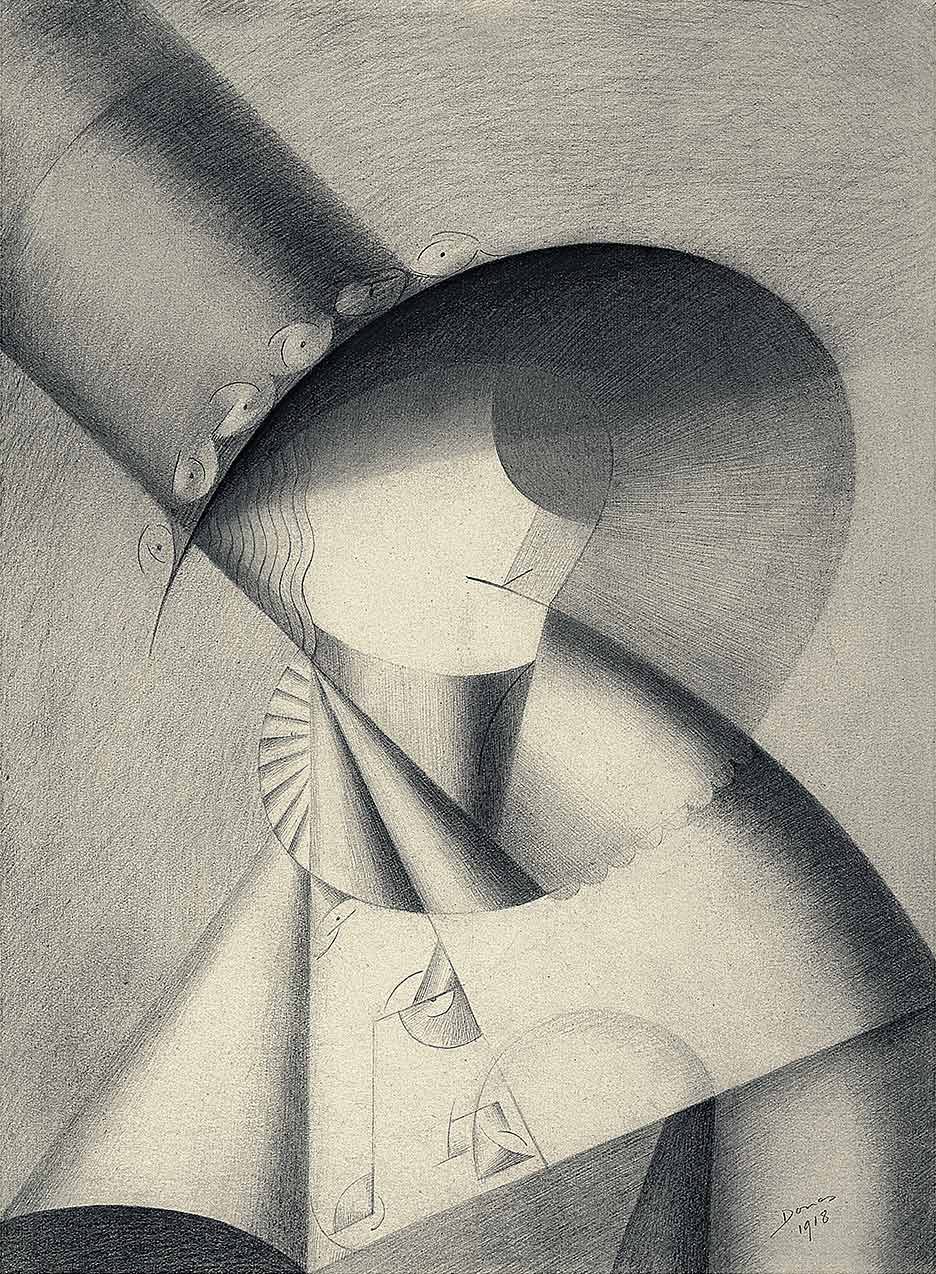

Several women artists first published their works under a male pseudonym – or at least gave themselves a neutral touch, such as Marthe Donas, who first entered the art scene under a neutral name, “Tour”. Very few artists succeeded in liberating themselves from the structures of gender-specific evaluation.

Detail: Signature “Tour Donas”

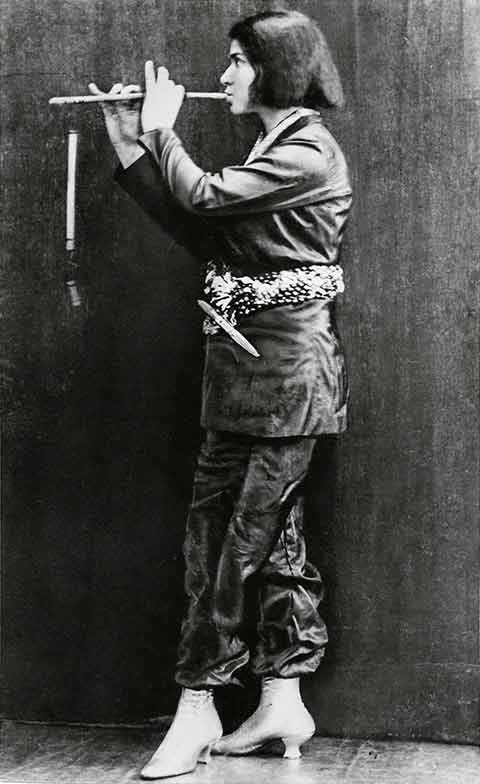

Alisa Georgyevna Koonen

I later found out that they were referred to as ‘the Amazonians’ in left-wing artistic circles, for they showed a somewhat martial spirit in all debates and discussions.

Frivolous and flighty?

As far as fashion goes, the woman depicted in 1915 by Sigrid Hjertén wearing a fur coat and red hat is spot on. Her head, with red cloche atop, is coquettishly cocked to one side. Her bob peeks out from below the hat, a short hairstyle revolutionary for women at that time.

Without batting an eyelid

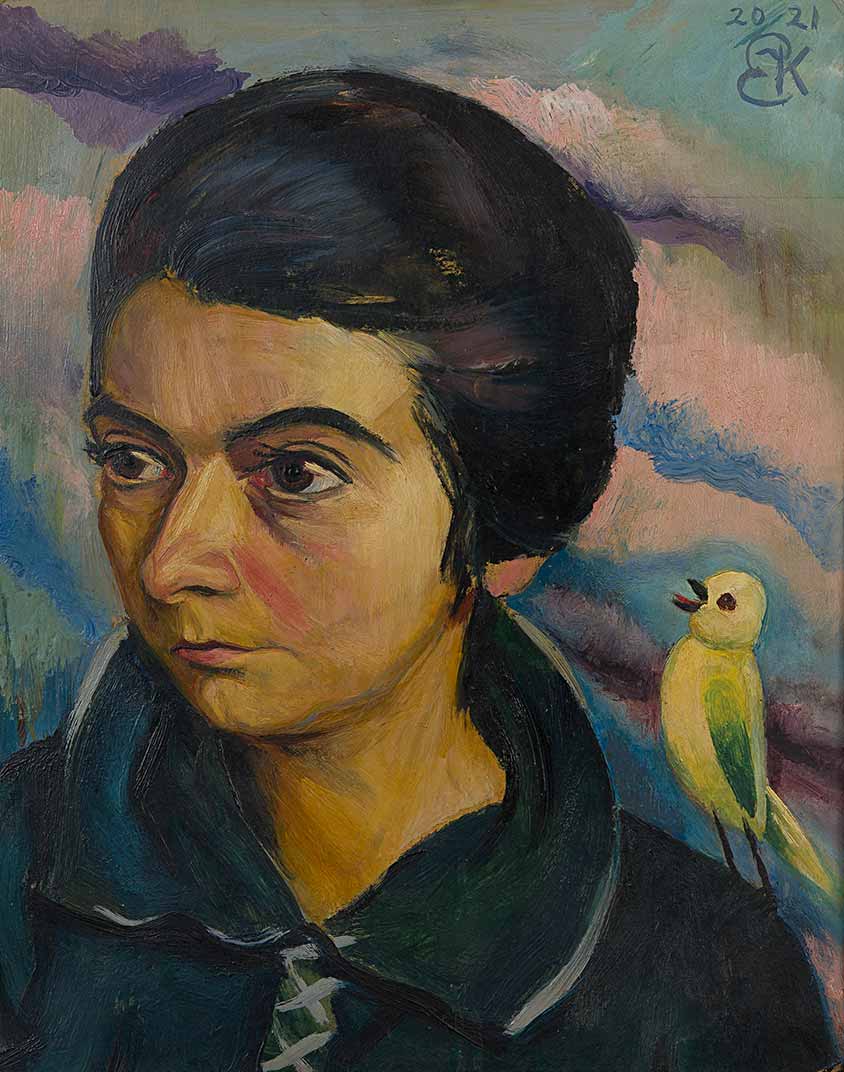

By contrast, the portrait of a young woman by Emmy Klinker does not have the flirtatious nature of Hjertén’s woman in a red hat.

A sign of Modernity: art as a lifestyle

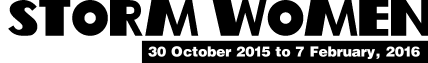

Combining the human body with abstract elements

The man and woman in the Toboggan troupe seem wild and dynamic. The full-body costumes worn by the two figures are essentially gaudy fields of color.

TOBOG

GAN

Dimensions of applied art

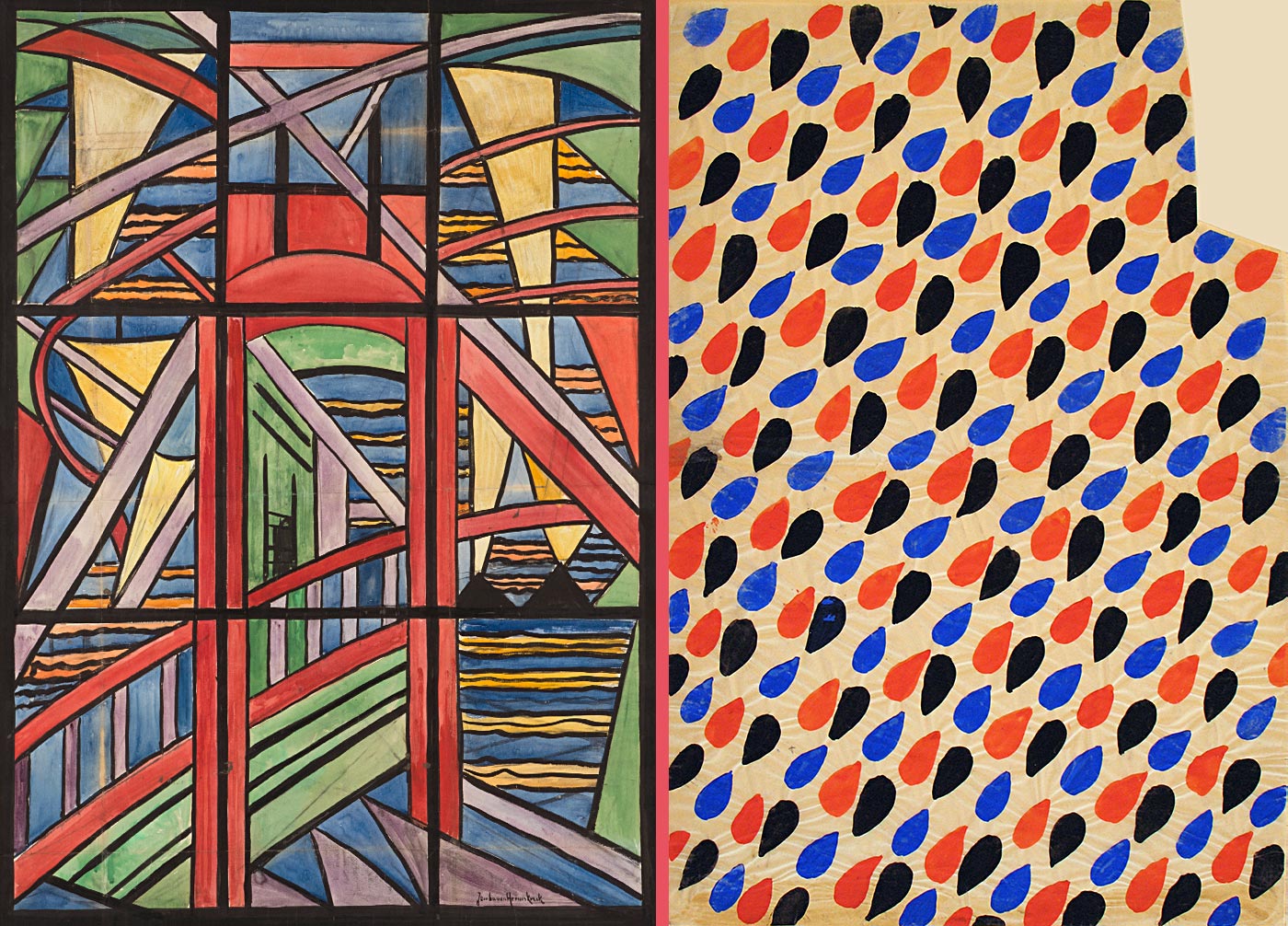

The art business offered many female artists a means of engaging in a creative occupation, earning money and expressing themselves. Art no longer only included painting, sculpture or architecture, but also embraced literature, music, dance, film, theatre, design or printing. Particularly in theatre but also in the field of design, the innovative spirit of artists such as Sonia Delaunay, Lavinia Schulz or Alexandra Exter was recognized. Female artists not only explored the interactive effect of individual colors at a theoretical level, but also tackled it practically. The color theories in applied art of the day are evident in Sonia Delaunay’s “Simultankleid” or Jacoba van Heemskerck’s glass windows.

Against the two-class society

The artists of the avant-garde incorporated everyday objects in their concept of art; this extended to things like furnishings and tableware, fabrics and fashion, theatre stage sets, book covers or glass windows.

In the STURM world view, the idea was to design all aspects of life through art. Founded in 1919 by Walter Gropius, the Bauhaus united art and crafts and as such represented a new form of art college.

Artist couples

Numerous STURM women lived in partnerships with artists – sometimes as married couples, but also in more or less open relationships, which were consequently not recognized by society. It was not rare for the women artists to be the breadwinners in the relationship.

They brought their private wealth into the partnership, but above all they earned more money with their applied art than their partners did from selling paintings. While the latter advanced their artistic careers, some STURM women moved into the applied arts, which their partners did not consider to be equal competition.

Pioneer of the sci-fi

Heed the signals!

The Red Planet and its inhabitants

The STURM legacy

The end of an era

Following their separation, Walden had made the remaining paintings from the STURM Gallery over to his second wife Nell. She fled the Nazis and managed to take them with her to Switzerland. It was not until the middle of the 20th century that some of them were auctioned, but there was no patching over the hole the Third Reich rent in European art production.

1932

The STURM women and their achievements were forgotten. Now we must tell their story anew!