The transmediale is already a remarkable event. For five days the Haus der Kulturen der Welt hosts a festival that no longer bears the name “festival”. Instead, the 29th edition is now known as transmediale/conversation piece. The conversation piece is actually a classic theme from painting, which featured most prominently during the rococo period: generally idyllic scenes of green spaces, where people held conversations in utter tranquility. Not so at the transmediale: “Here no one should feel at ease”, says Artistic Director of the event Kristoffer Gansing. He’s talking in a room known as the “Panic Room”, a location for open discussions that stretch over four hours.

Kristoffer Gansing, artistic director of transmediale (c) transmediale

The urge and the unease

The themes discussed cover such topics as how power is distributed on the Internet, why the sharing economy is in the hands of a few big firms, or the innocent early days of the Web, before giant corporations like Google and Facebook, when global networking still seemed like an achievable utopia, albeit of course the utopia of a small avant-garde of hackers and Internet activists. But the topics also cover the failed revolution of the Arab Spring, which began precisely five years ago at Tahrir Square in Cairo. Primarily political themes, therefore. The different segments of the transmediale are called “Anxious to Act”, “Anxious to Make”, Anxious to Share” and “Anxious to Secure”. Here it’s hard to forget the double-meaning of the word “anxiety”: On the one hand it refers to the urge to do something, but on the other it signifies unease.

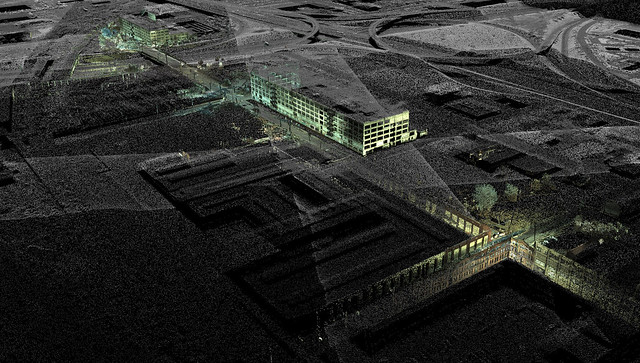

Hello, City! by Liam Young (c) Liam Young

Nobody picks up the telephone here

If you’re out and about in cities like Washington, Brussels or even Frankfurt, you’ll soon find yourself thinking: These might not be the cultural centers of the Western world, but here the threads of the world of finance meet those of European and American politics. Faced with the mirrored façades of anonymous administrative and business architecture, unease spreads. You can’t see what goes on inside them. It is with this image that the transmediale began on Wednesday evening, when the film “Parallelogram” by Steven Rowell and Brian Holmes was shown in the large auditorium of the HKW. What we see are buildings so dull that they wouldn’t be out of place in commercial districts of Germany. In almost every composition the American flag is just visible, reflected in panes of glass or right at the end of the image. The banal office buildings are the central offices of the National Rifle Association, the American Meat Institute or the American Petroleum Institute. From off-screen we can hear the answerphones of these conservative lobbying organizations: Nobody picks up the telephone here.

The new heroes

The work by Holmes and Rowell naturally aims to expose something and in doing so runs the risk of knowing all too precisely who the baddies are. The claim is informative: to make visible what normally remains hidden behind reflective glass façades. In similar fashion, most of the works discussed at transmediale are the result of many hours of research. “Research-based artworks” is often murmured on the podiums. It seems as if this type of art has found new heroes. Names like Edward Snowden or Chelsea Manning appear time and again, as does Trevor Paglen. Whistleblowing as an artistic practice: Paglen hovers somewhere between investigative journalism, photography and concept art, and it is only for this reason that he has not come to the transmediale in Berlin, because he has other obligations apparently.

National Rifle Association, from Parallelograms, (c) 2015 Steve Rowell

Paranoia as a default state

However, one project is presented that Trevor Paglen realized jointly with online activist Jacob Appelbaum. Title: “The Autonomy Cube”. It is a Plexiglas cube with edges measuring 50 centimeters, which stood in the Edith Russ Haus in Oldenburg for an exhibition. The model is Hans Haacke’s “Condensation Cube” from 1963. Instead of condensation, in Paglen and Appelbaum’s version four WiFi routers are installed, via which the museum visitors could access the Internet. This was not just any old connection, however, but one that went via the encryption network TOR. This facilitates an Internet connection that cannot be traced.

Trevor Paglen & Jacob Appelbaum: Autonomy Cube

The stuff of utopias and horror stories

So, paranoia as a recommended basic attitude in the 21st century? Perhaps. The dystopias of the 20th century present a dismal future of possible nuclear war and fascist regimes. The future is here, and naturally looks different to the vision presented in the films that Florian Wüst, curator of film and video, showed in his program. The film selection is like a review of the future. It includes Jean Herman’s oldest film “Actu Tilt” from 1960, a montage of rocket launches and slot machines, the vision of a forgotten future. Hellmuth Costard’s “Echtzeit” from 1983 is a little reminiscent of “The Matrix”, only here the hero does not want to escape the simulation, but rather enter it. This film is also very fitting for the theme of technology as the stuff of both utopias and horror stories at the same time.

Photo by Julian Paul

An alternative social practice

An approximate idea of what the transmediale is all about can be gauged from the names of the guests. Jussi Parikka, the Finnish media theorist, took part, as did Ben Vickers, curator of everything digital at the Serpentine Gallery in London. Time and again we see the media artist Siegfried Zielinski flitting through groups of beer-swilling festival-goers. The only downside is that aside from a few scattered installations, this year there is no exhibition at Haus der Kulturen der Welt, unlike in previous years. It’s as if a discussion marathon were the only possibility of getting to grips with the present – and ideally the future. But there is still a supporting program, the CTM Festival. Parties have been taking place in Berlin clubs since January and continue during the festival: an alternative social practice in place of the podium discussion.

Serpentine Gallery Curator Ben Vickers, Photo by Julian Paul