From studio to dining table: Art with a chef’ hat

10/08/2024

11 min reading time

Are artists especially creative when it comes to cooking? A glance in the kitchens of the art world. This time with a short chronicle of artists’ restaurants, from Daniel Spoerri to Jennifer Rubell.

Allen Ruppersberg and Les Levine serve filet of tree bark and Halifax salmon steak

In the 1960s, many young artists felt a similar impulse to place everyday places and objects at the center of their work. As an artist, the idea of donning the role of running a restaurant fitted perfectly into this age of artistic upheaval. In 1969, two restaurants based on this principle opened in the United States: Allen Ruppersberg’s “Al’s Café” in Los Angeles and Les Levine’s “Levine’s Restaurant” in New York. Al’s Café opened on Thursday evenings and resembled a classic American diner, although a glance at the menu revealed many a hard-to-digest meal such as “three rocks with a scrunched up piece of paper”, “filet of tree bark” or “cotton with stardust”, an ironic allusion to the Land Art movement evolving at the time. After an order was placed, Ruppersberg then prepared these sculptural meals and served them; guests consumed them at their own risk. That said, real beer was on sale and over the three months of its existence the café (part installation, part participatory performance) in this way soon emerged as a popular meeting point of the local art scene.

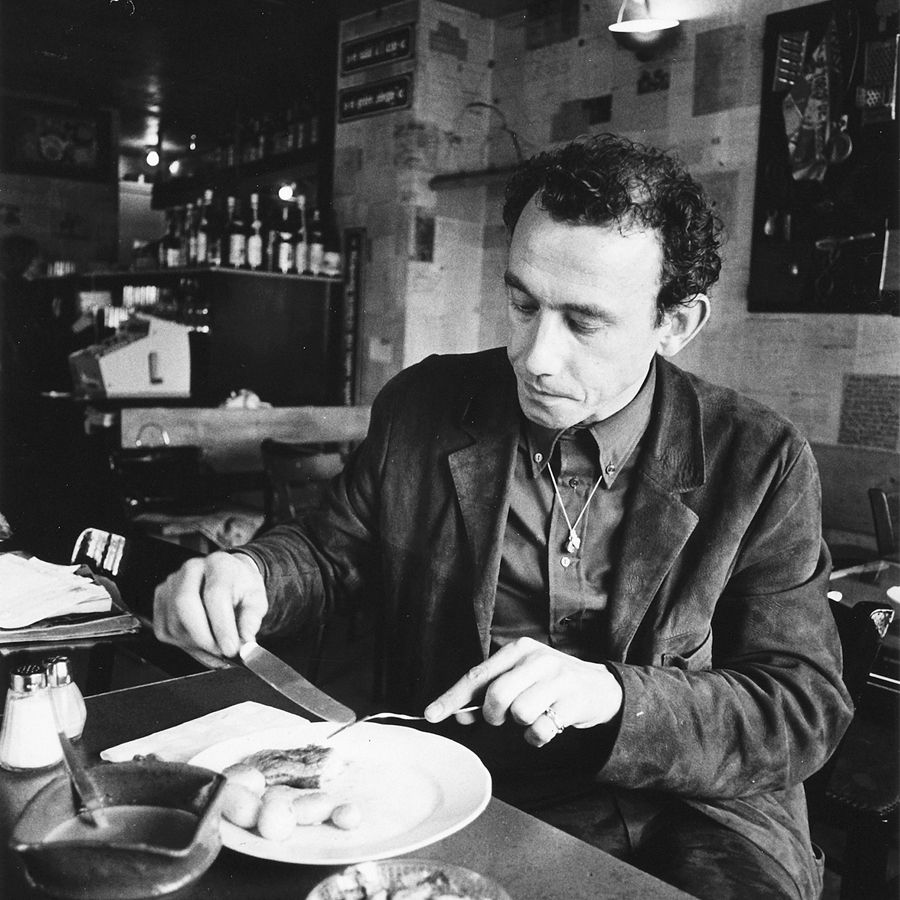

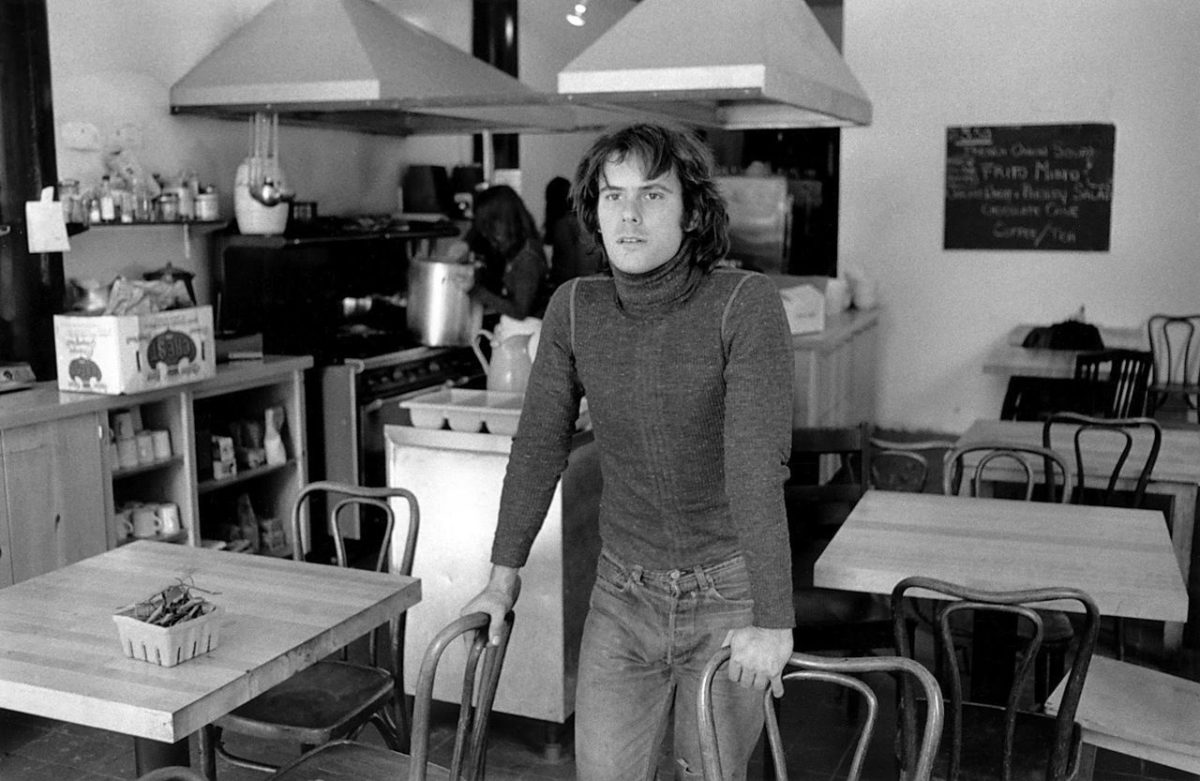

Gordon Matta-Clark serves oxtail soup and frog’s legs

What was probably the artist-restaurant project of that era which ran for longest was “FOOD” (1971–3), opened by Gordon Matta-Clark, Carol Gooden, and Tina Girouard in New York’s SoHo district. It was run entirely by artists and was the only eatery in the district that offered healthy, sustainable, and affordable food; within a short space of time, the restaurant had become highly popular and a central meeting place for the creative scene. Matta-Clark organized regular performances there, such as his “Bone Dinner”, during which he served oxtail soup, followed by roasted marrowbone dumplings and frog’s legs. At the end of each evening, each guest was given a necklace made from the bones left on the plates. FOOD evidently succeeded effortlessly in functioning as a restaurant, a social experiment and a participatory artwork, whereby the latter term did not really gain sway until over 20 years later.

Jennifer Rubell serves a vast range of brunches

Well before Tiravanija opened his Art-Basel pop-up restaurant, another artist had dedicated herself to providing the public at the Swiss art fair with culinary and artistic fare: Jennifer Rubell. From 2002 to 2018, each year on the occasion of the opening week of Art Basel Miami Bech the US concept artist and daughter of famed collector couple Mera and Don Rubell invited everyone to a monumental breakfast in the courtyard of the Rubell Family Collection. Rubell opted for a classic menu: Sometimes there were hard-boiled eggs, croissants, and bacon; other times porridge with raisins; or yoghurt; or Danish pastries, donuts or bread with butter and salt. The way the food was served was anything but conventional. Part installation, part interactive food performance, in “Faith”, 1,573 pastries were balanced on a giant seesaw; in “50 Cakes”, the Rubells spoonfed their guests by hand with chocolate, vanilla, and strawberry cake; at “Just Right”, the public was left completely to its own devices. Borrowing from the fairytale of Goldilocks and the Three Bears, you had to clamber through a hole in the fence into a derelict house, grab a bowl and spoon from two huge heaps, serve yourself porridge from huge, steaming pots, and grab a sachet of sugar, a box of raisins and then get some milk from one of the large fridges.

Rubell, who is also a trained cook, initially rejected the idea of defining her brunch installations as art. However, the participants in the food performances constantly enquired after the name of the artist behind the events and in 2009 the influential art critic at the “New York Times” Roberta Smith labeled a contribution Rubell made to Performa 09 as a “successful melding of installation art, happening and performance”. Only then, and on recognizing how closely her ideas were related to Tiravanija’s concepts and the principles of relational aesthetics did Rubell start to present herself openly as an artist.

You may also like

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consetetur sadipscing elitr, sed diam nonumy eirmod tempor invidunt.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit

- Context

Hans Haacke in New York

- Interview

About Time. With Marie-Theres Deutsch

- Context

These boots are made for walking

- Context

Seeing nature anew – through a cube

- What’s cooking?

From studio to dining table: What a festive spread!

- Video Art

Lifting the veil

- Context

A new look at the artist – “L’altra metà dell’avanguardia 1910–1940”

- Context

The film to the exhibition: Hans Haacke. Retrospective