From studio to dining table:

Art with a chef’s hat – Pt. 2

03/18/2025

10 min reading time

Are artists especially creative when it comes to cooking? A peek into the art world’s kitchens, this time with the second instalment of our short chronicle of artists’ restaurants, from Futurist taverns to Senegalese juice bars.

The Futurists served exalted pig

In March 1931, an eatery opened in Turin’s Via Vanchiglia that was consciously meant as an affront to traditional Italian hospitality: “Taverna del Santopalato”. The manager was none other than Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, founder of the avant-garde art movement of Futurism that set out to comprehensively revolutionize society. Just standing art on its head did not suffice for such a task, he felt. Eating and thus food also needed to be radically reinterpreted. Together with Luigi Colombo (alias Fillìa), in 1930 Marinetti penned the “Manifesto for Futurist Cooking”, essentially an instruction manual for an ultramodern cuisine and something that was put into practice in the tavern.

The restaurant was designed to be a temple to the Futurists’ ideals, which included modern technology, industry, speed, and science, not to mention notions that were chauvinistic and glorified war. In order to make very sure that absolutely no sense of coziness arose, the Santopalato boasted spotlights instead of candles, and the walls were clad in aluminum. The Futurists’ fascination with the aesthetics of modern aviation was also reflected in the entire restaurant experience: The guests took their meals in a kind of aircraft cabin, tables and chairs all had slanting angles and vibrated, while the sound of engines emanated from the kitchen. And the objective was to ensure there was no lack of fuel, so Lambrusco was poured from gas cans.

Marinetti conceived of the act of eating as a multi-sensory gesamtkunstwerk: For example, if you ordered the “air meal”, you were served a plate of olives, little pieces of fennel, and kumquats, and were instructed to eat these with your right hand while using your left hand to stroke alternately over sandpaper, velvet, and silk. In order to intensify the sensory experience, the waiters sprayed the air with the fragrance of cloves. The Futurists’ maxim of “Innovation instead of Tradition” was also in evidence in the guise of what were at the time unusual combinations of tastes (chicken with whipped cream, dried fish with cherries) and the unconventional names some dishes were given: “Piquant airport”, “Colonial fish with Drum Roll” or “Exalted Pig”. The latter consisted of a slice of salami floating in hot espresso and seasoned with a shot of eau de cologne.

What was possibly Marinetti’s most radical culinary proposition was, however, his complete rejection of any pasta dishes. He claimed they made you sluggish and tired and were therefore not suited for patriots with all the “dynamic duties” they had to fulfill. The Santopalato menu card logically did not include a single type of noodle.

Tobias Rehberger serves Vodka Lime&Soda

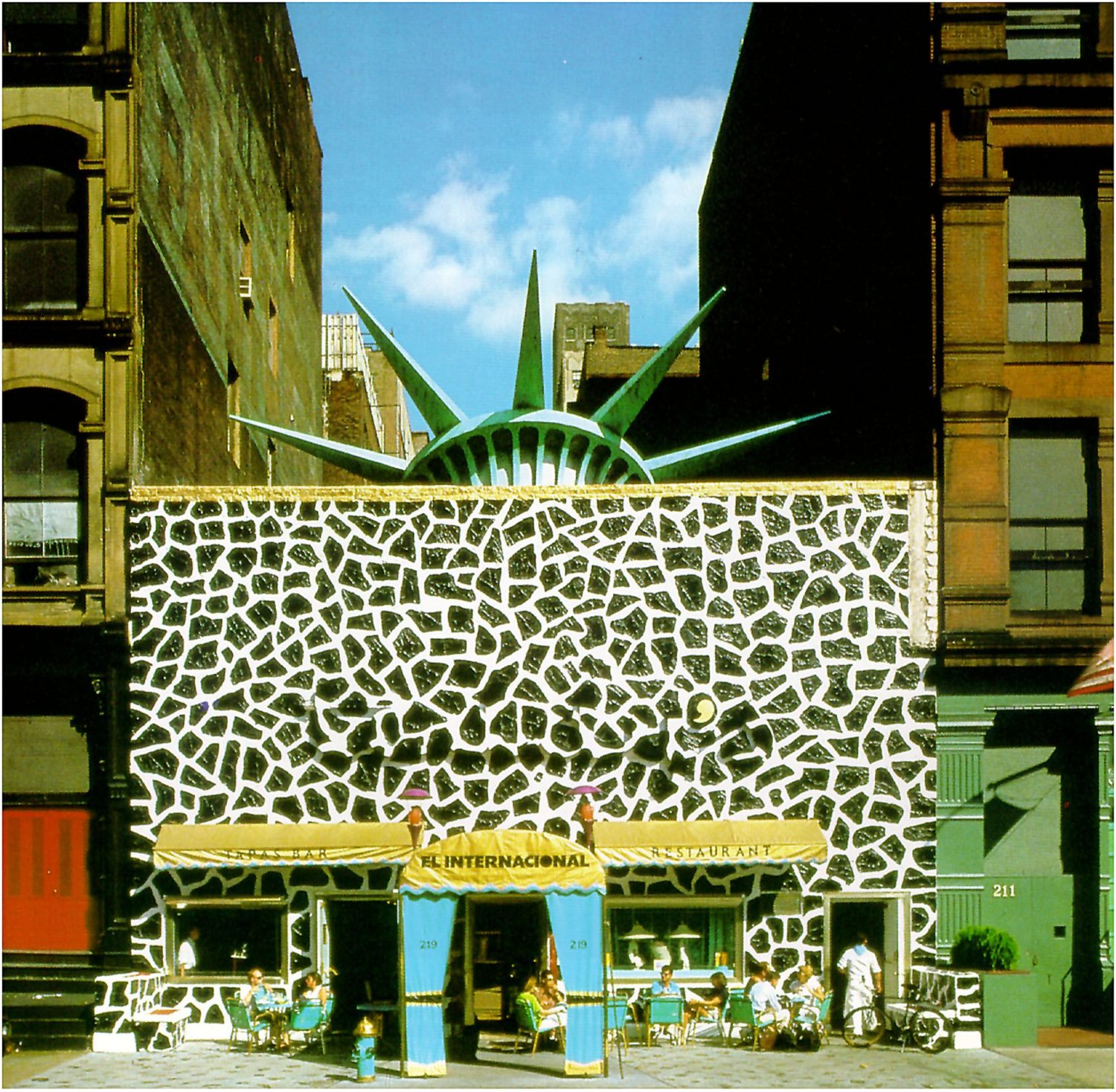

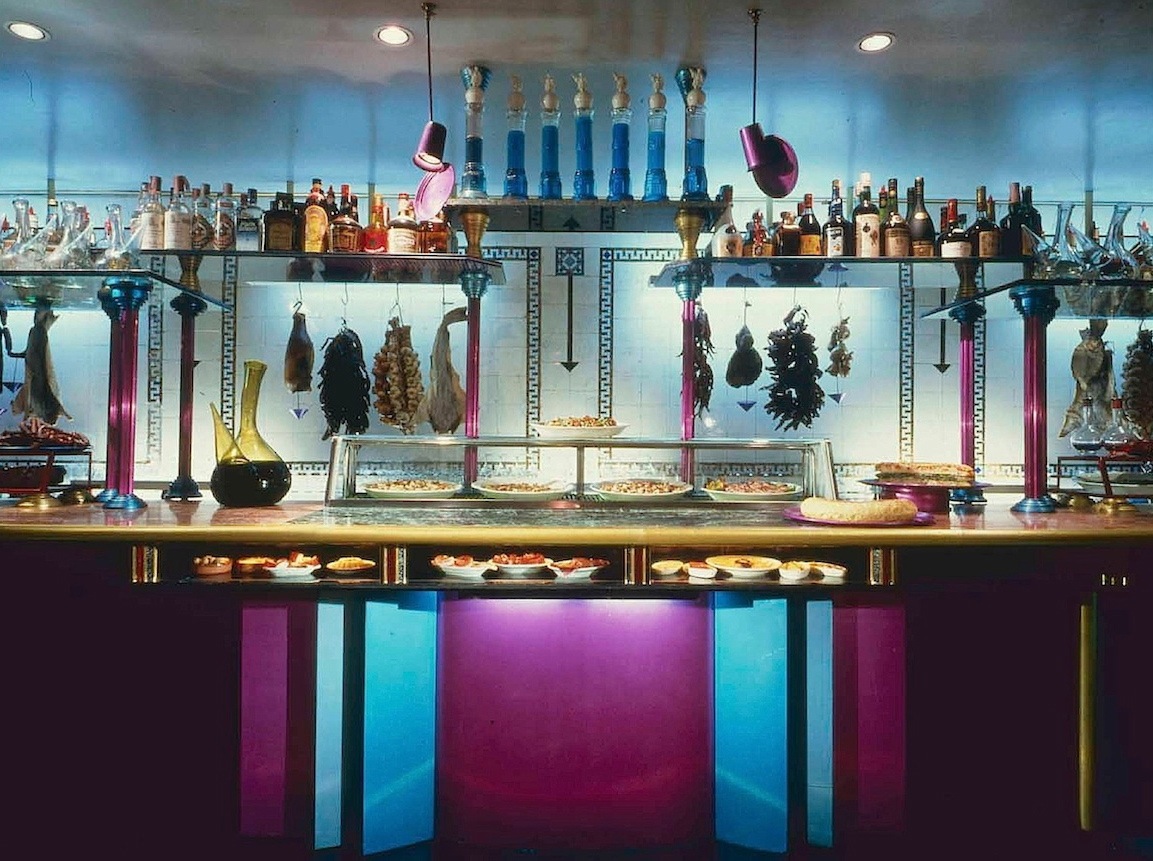

While Miralda only took his favorite dishes with him to New York, Tobias Rehberger went one step further: In 2013, he packed his favorite bar in Frankfurt up in a crate, and that even included the coat hooks and radiators, and sent it as freight to Manhattan’s Chelsea district. In 1987, shortly after it opened, Rehberger stepped foot for the first time in the relatively unassuming “Bar Oppenheimer” in Sachsenhausen, and 35 years later he evidently still could not get enough of it. On the occasion of the Frieze Art Fair, the sculptor and installation artist had the narrow, long bar reconstructed in the selfsame proportions in the Hotel Americano’s basement, and the new version even sported the exact same fit-out. It was still as good as impossible to recognize the bar as Rehberger had disguised it as a dazzling artwork: All the surfaces, from the floor to the ceiling, were covered in a black-and-white zigzag pattern, with orange lines added here and there. He had been inspired by the dazzle camouflage used in World War I to protect British warships.

In 2024, the artist recontextualized the piece on behalf of the Diriyah Biennale in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, this time as a collective project with Senegalese chef Youssou Diop. The new version was named “NJOKOBOK” as was the collective, and instead of orange juice, the duo served mint tea as well as a locally produced juice made from Senegal hibiscus and Arab basil. In order to open up the closed system of the Biennale and take up Šušteršič’s concept of art as social practice, they invited migrant communities to tell their stories at the bar.

The Futurists primarily intended the Taverna del Santopalato to amplify their artistic-political standpoint. Miralda, by contrast, needed the collaboration with his guests to activate his gesamtkunstwerk; Rehberger used the guise of a bar as disguise in order to hide his art. Šušteršič, for her part, aligns her work entirely to the audience and thus follows the overarching motto of all hospitality: The client is king/queen.

You may also like

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consetetur sadipscing elitr, sed diam nonumy eirmod tempor invidunt.