Who does not know Ulay? But who really knows Ulay and his work? An artist, who is wildly influential, fabled for the collaboration with Marina Abramović, though somehow oddly hidden when it comes to his vast, powerful solo oeuvre – “hard to find, to know, to get a critical handle on” as the theoretician Dominic Johnson so greatly put it in an article.

Born as Frank Uwe Laysiepen in 1943 in the German town Solingen, he grew up in a postwar atmosphere and left for Amsterdam in the late 1960s. There, despite his nomadic way of living, he planted roots for over 40 years until he moved to the capital of Slovenia, Ljubljana, because of love. He lived in Ljubljana until his death in March 2020.

Ulay was a chronicler of the social revolutions

The Stedelijk retrospective “ULAY WAS HERE”, the largest-ever and the first international posthumous exhibition of the artist, is bringing Ulay back to the city that influenced him so much and vice versa; Ulay was a chronicler of the social and cultural revolutions taking place in Amsterdam at that time and one of the cofounders of de Appel. The exhibition examines the majority of the artists’ oeuvre, expanding and extending the notions of what has ever been presented before. Rethinking the importance of his work anew, “ULAY WAS HERE” positions the artist as a pioneer of Polaroid photography, performance and body art.

I’m not a signature artist

as moons and seasons and years change, so does my mind: change, change, change, through change consume change...

Identity through change...

These are some of the first lines Ulay wrote in his notes in August 2015, when he was preparing for the survey exhibition ULAY LIFE-SIZED at Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt in 2016–2017, curated by Matthias Ulrich. Ulay himself addressed the complexity of his work similarly on more occasions, calling his oeuvre “bizarre”. “My oeuvre is so bizarre. I jump. I’m not a linear, consistent, producing artist. Most artists, once their handwriting is recognized, they stick to it. For the public, for critics and collectors, and for the market, that is much easier, more convenient. My ambition is almost the opposite: each time I do something new, I choose different motives, different techniques, different dimensions and so on. That can be very confusing, but I like to have joy too. (…) And once it is done, I let it go.”

While it is impossible to summarize the artist’s diverse and complex body of work on the intersection of photography and performance in a few sentences, some things are certain: Ulay conceived most of the works in his oeuvre as projects. But not to frame them or himself, in contrast: to be collaborative and in contact with the social fabric, to be open to chance by means of the process. His major commitment was, according to art critic Thomas McEvilly, to always create a “coherent world in itself.”

My oeuvre is so bizarre. I jump. I’m not a linear, consistent, producing artist.

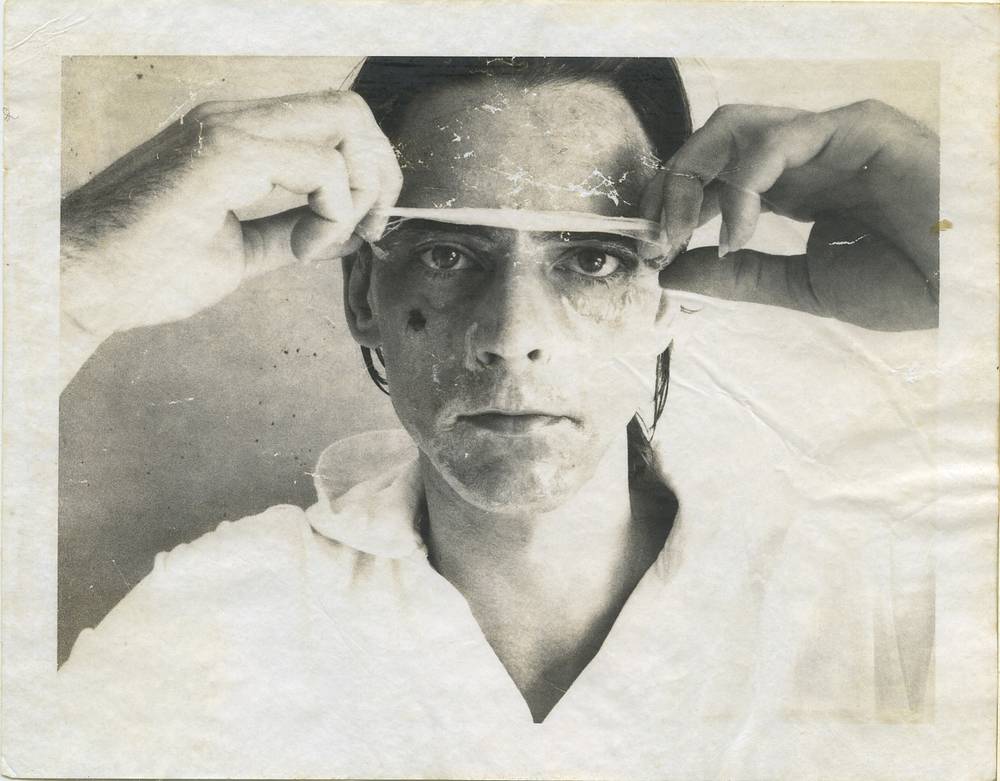

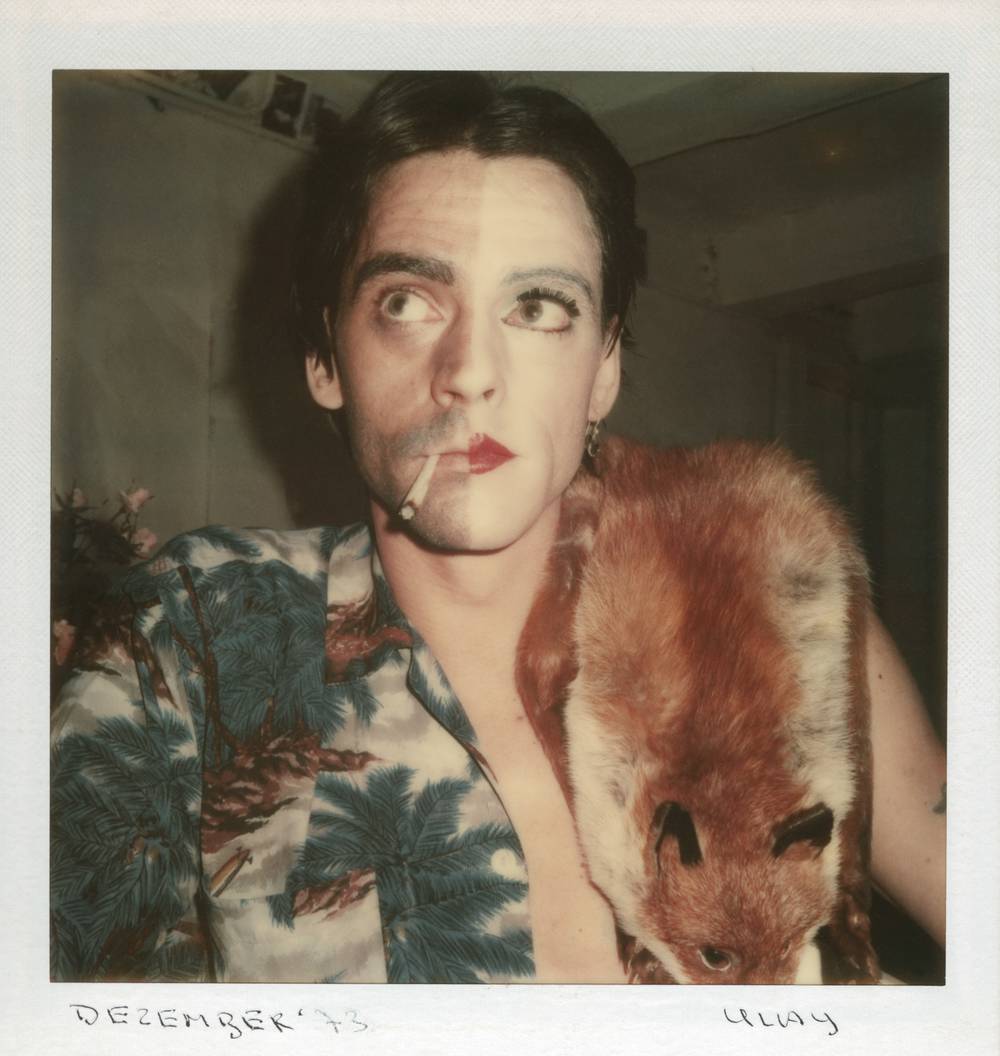

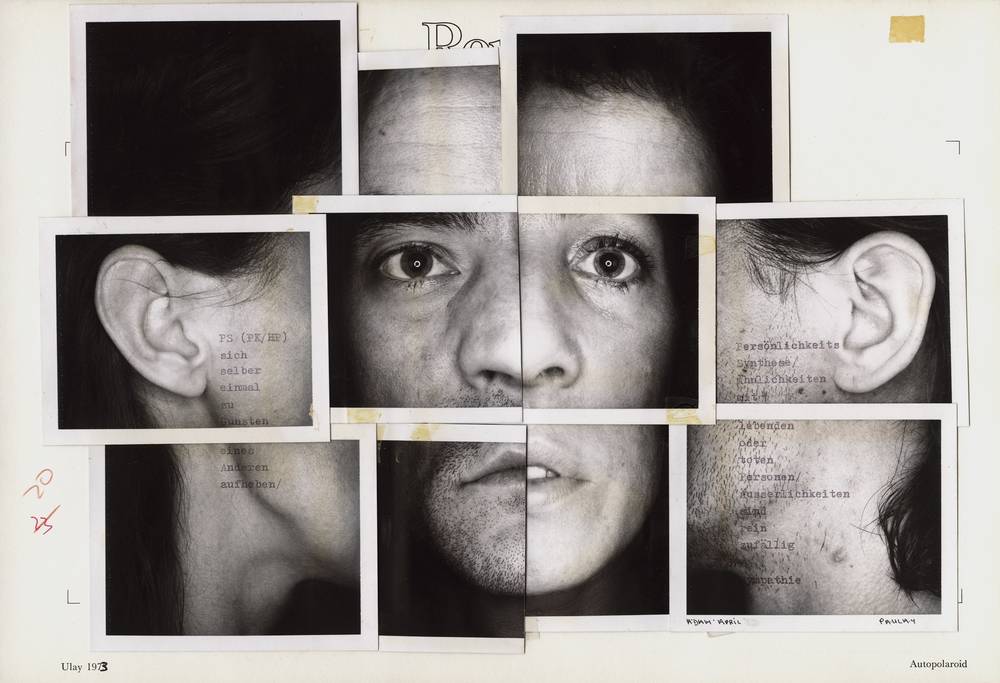

Additionaly, Ulay has dedicated himself to the lifelong creative process of exploring the limits of his own identity, whether through (Polaroid) photography or the medium of his own body. By presenting himself as a fluid subject in relation to the Other – different sex/gender; close friend, partner, or lover; people on the margins of society; cross- dresser, native/foreigner; as Everyman – Ulay created community, explored relationality, and lead us to reflect on the fluidity of our own multiple selves: who are we and with whom? Ulay’s exhibition at the Schirn was one of the artists’ first that dared to address and examine this question more in depth.

Who are we and with whom?

It was also visited by Rein Wolfs, now the director of Stedelijk Museum, who was so impressed by Ulay's work, that he initiated “ULAY WAS HERE”, co-curated together with Hripsimé Visser. The retrospective was borne from an art-historical responsibility to Ulay and the city of Amsterdam more broadly (Ulay left an indelible mark on the city), Wolfs told Artnet News: “Given the mounting interest in the performance art of today, it is time to re-evaluate the history of the discipline and the backgrounds of the artists who shaped it”.

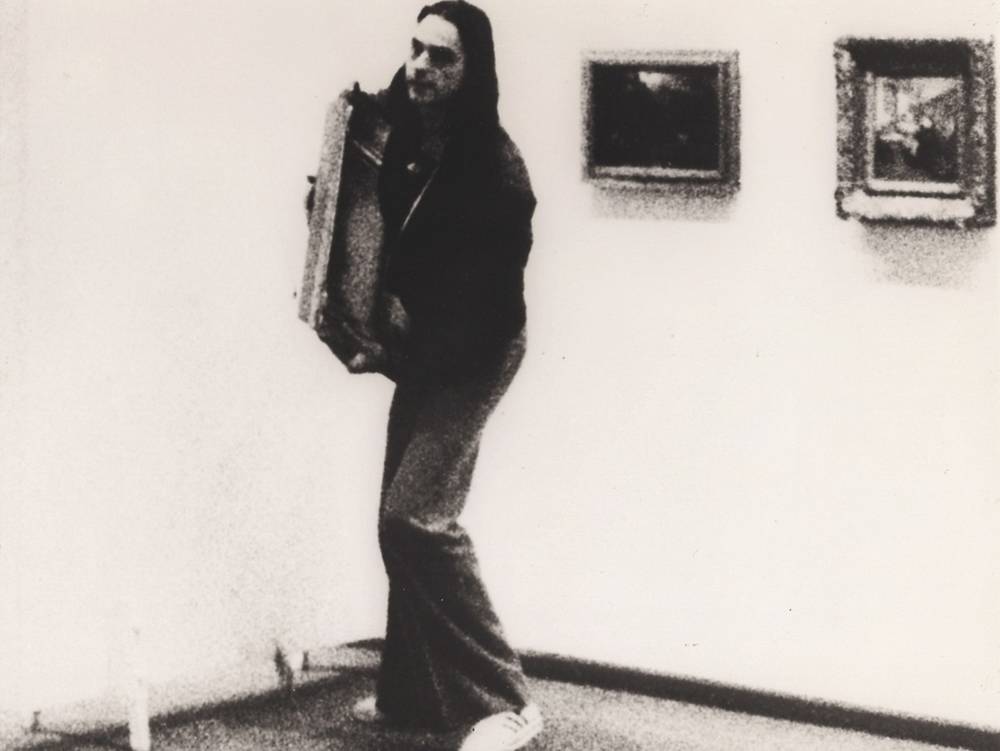

“ULAY WAS HERE” examines the artists’ oeuvre as a whole. It guides the viewer from Ulay’s early typewriter aphorisms and visual poetry from the seventies, his photographic documentation of the then anarchic Amsterdam, to his last performances and performative-photographic works, conceived during the last three years of his life (2016–2019). Among others, for the first time on view without any copyright issues (certain people claiming the ownership of the work for years) is the iconic art-theft “Irritation – There is a Criminal Touch” (1976) and the fully chronologically presented “FOTOTOT” series, in which the artist confronted himself with the ever-changing nature of the photographic image and the notion of the live audience.

Presented in detail – at an Ulay solo-show – are finally also many early and later joint works with Marina Abramović. The exhibition also highlights the more meditative, spiritual and theatrical work by Abramović/Ulay; for example, the large-format Polaroids, dating from 1980 onwards, which were not part of The Cleaner, the Abramović travelling retrospective.

Two events marked the whole exhibition-making process: Ulay’s passing on 2 March 2020, and Covid_19, which reached Europe less than two weeks afterwards. Despite Ulay being so energized, humble and involved in the preparation, his physical absence affected the retrospective and still affects time and space. And so does the absence of the other bodies due to the pandemic.

Whilst the Schirn show had been, as Ulay said, created with a wish to present “a wild show ‘quer durch den Garten garten’ for a greater amazement,” the Stedelijk one is not just empty (still!), but also more clearly directed, curatorially more formal and traditional. This does not only result from the white cube frame of the galleries in the Stedelijk’s old building, but it is also the Covid-19-regulations that affected the dramaturgy of the exhibition, the movement of its visitors, the experience of the exhibition in itself, which became more regulated than ever before. Working on the exhibition in the first year of the pandemic after Ulay passed away, the whole team faced many challenges. And we still do.

Ulay called himself a “hideaway artist”: “I have done so many things that people don’t know about – they can’t know because they don't have access to my archive.” With the exhibition still being closed, Ulay is not hiding, but is in this case, being hidden. This is painful and frustrating, especially in the context of a presentation of such a kind. With Lena Pislak, Ulay’s wife and with him the co-founder of the ULAY Foundation, based between Ljubljana and Amsterdam, we were from month to month eagerly waiting that the Dutch government lifts the lockdown measures...as this does not seem to happen, we accepted the situation. Ulay would have gracefully accepted it. With the monumental Stedelijk exhibition – hopefully soon travelling to another venue – and the rising interest in his work, leading to its re-contextualization, Ulay was not only here but is here to stay. That is a fact. Also, if it takes some more time to meet with his work in person.