The beginning of a conversation and the wait for an answer – that is what the title of this year’s Städelschule Graduates Show, “The Call”, is meant to evoke. The exhibition catalog by Johanna Laub, coordinator and curator of the exhibition, explains how the works by the 26 graduates are ultimately the result of just such an intense exchange and dialog between students, professors, and teachers. A look at individual positions reveals the artistic diversity among the graduates.

The very moment you step into the foyer of the repurposed building, you’ll see works by Benjamin Tiberius Adler and Eric Powell. Adler, who studied law before his degree in fine art, has installed a figure-of-eight sculpture made of law books, through which a cycle of water flows. His work, “Down the Drain” thus alludes to the constant impermanence of these kinds of treatises, which have to be updated with every legislative period and change in the law.

A few meters further on in a passageway, we encounter the work “Following the Protocol” by Dmitry Teselkin. His installation consists of a layer of cardboard boxes playfully arranged to cover all the walls of the corridor as well as the doors to the toilets. Might this layer be a kind of protective device for the stone wall that stands behind it? Is it a metaphor that asks about our own human need for protection?

One room further on, we find a rolling door whose shape is modelled on a guillotine. With “White Lie”, as this work is called, Jiyoon Chung connects domestic, everyday, and violent elements until complex questions arise: Do I dare to step through the narrow gap and thus under the blade of the guillotine? And what emotions and feelings are triggered by these thoughts?

BETWEEN VIOLENCE, AUTHORITY, AND DISCIPLINE

In her work “Prop 1.a”, artist Emilie Estrid Kjær, for her part, covers prop-like lecterns with pastel-colored fabrics decorated with fine floral embroidery. These are reminiscent of patterns that might typically be found on household goods such as toilet paper, kitchen roll, or tea towels. The patriarchal and authoritarian power that emanates from lecterns in a political context, for example, is thus thwarted by a domestic aesthetic.

The same room contains the installation “About the Weight of a Tragic Eyelid” by Thuy Tien Nguyen. The surface of the platform-like structure is covered by a black-purple liquid, which is touched by vertical steel sculptures. The work picks up on elements of the Vietnamese education system and reflects rigid, disciplinary moments in school education. A platform like this serves teachers as a kind of stage from which they arrange their lessons and thus marks the hierarchy between teachers and pupils. The metal sculptures look like oversized fountain pens, the material of which evokes the coldness and hardness of the school system.

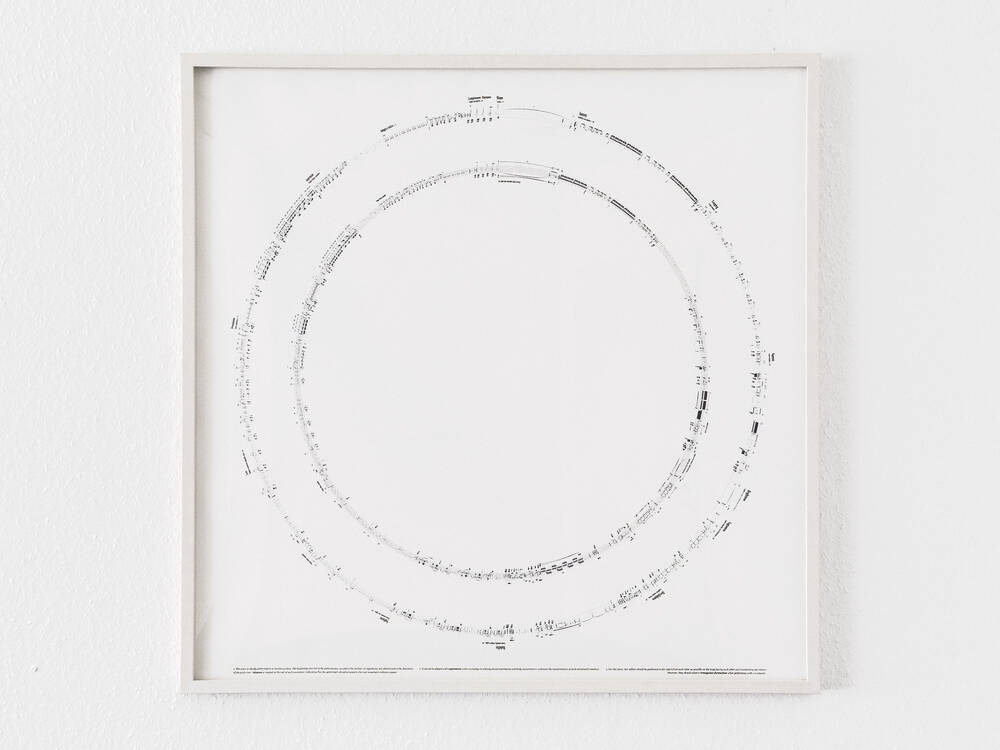

From the odd closed office door, meanwhile, sounds and noises emerge that arouse visitors’ curiosity. As we enter one of these rooms, we come across the sound installation “Binary Composition for Two Cellos” by Donghoon Gang. The sounds of two cellos emanate from two small loudspeakers. These stringed instruments produce melodies that go from fast and rhythmical to slow and sluggish, from cheerful and harmonious to melancholy and discordant. The score for this polyphonic instrumental piece is mounted on a wall and structured in a circular system of lines that suggests an endless musical loop. In conversation with the artist, who studied music and philosophy before his degree in fine arts, we learn that the shape of a cello reminds him of a human silhouette, while its tones remind him of a human voice. “Allegro, vivace, largo” – these musical terms have been replaced by the artist with emotions such as “anxiety”, “sorrow”, or “love”. It is not only the tempo and the rhythm, but also the dissonant or harmonic intervals of the melodies that create different feelings and emotions. The cellos thus become representatives of individual humans, who react to each other through their voices and support, argue, and are reconciled in an ever-recurring cycle.

SOUND, SOUND, SOUND

At the end of the corridor, in an entirely darkened room, there is another sound installation – this time by Mahya Ketabchis. We hear undefined tones ranging from metallic, industrial, and instrumental sounds to nature-like noises, triggering a wide variety of associations. In “Study of a Search”, the focus is on the emotional and sensory experiences that are triggered in the listener by the sounds of the installation.

Voices and conversations coming from other artistic works, meanwhile, hint at private and personal stories behind individual office doors. In Sopo Kashakashvili’s installation “Other-Hood (Act II)”, a red velvet fabric covers the entire floor of the office space. In the middle stands a wooden box with a loudspeaker on each of its sides. Different narratives can be heard, told in apparently computer-generated, female-sounding voices – they are interviews with first-generation migrant mothers, who talk of their experiences and stories, including since they have lived in Germany. The box is printed with images of protest movements from the respective countries of the interviewees. The ceiling of the room is adorned with red figurative works bearing the words “De-Heimatize Belonging” – a term coined by sociologist Bilgin Ayata. With it, she opens up a feminist, anti-racist discourse on belonging and questions the meaning of “home” and “belonging” in a migrant context, whereby she also places these terms within a colonial and racist (conceptual) history.

Discarded glass shower panels are arranged in modular stone blocks and fill part of the room. The logo of the Leonardo Hotel in Frankfurt am Main can be seen on the glass. They were left outside the hotel as it underwent renovation, and artist Nina Nadig salvaged them. Her work “Leonardo” thus reflects the boundaries between private and public property and questions the dictates of private ownership. The grid-like arrangement of the glass panels in the exhibition space reflects the rigid and repetitive architecture of the hotel, while the modular installation, which can be arranged and moved at will, creates a playful moment.

The hotel’s logo – the Vitruvian Man by Leonardo da Vinci – symbolizes the image of the perfect male body and thus not only raises questions about body norms, but also about a person’s presence as an artist. The perfectly formed individual, drawn by the master of the Renaissance, calls their own artistic ability into question and shines a light on constant self-optimization, born of insecurity, as a human being and an artist.