A variety of objects are gathered in the SCHIRN Rotunda at present, all of which could have come from the storerooms of architects and town planners. The colorful benches, pillars, and wall elements created by Slovenian artist Maruša Sagadin invite passers-by and museum visitors to engage with their built environment. While the seating asks the question of who can sit where downtown, the wall-divider addresses the role of spaces to retreat to in the public realm. The pillar with the high-hanging network of chains encourages us to think about how spaces are designed for ball games but can also be read as a commentary on urban planners’ priorities. With its hanging “crown”, the sculpture challenges us to reflect on the needs that get privileged or ignored in the urban space – and invites visitors to use their own bodies to take a stance.

Who decides the design of spaces?

The question of for whom and by whom spaces are devised and designed plays an important role in feminist approaches in architecture and urban planning. Founded in London in 1981, the Matrix architecture and design collective published “Making Space. Women and the Man-made Environment” in 1984, which ascertains that architecture is not only built primarily by men, but also predominantly reflects patriarchal living and working habits. The group, which is not itself hierarchical, counters this model by creating building projects that foreground the needs of women and marginalized groups. While the “Dalston Children’s Centre” (1984-5) does justice to children’s requirements, the designs for the “Pluto Lesbian and Gay Housing Cooperative” (1987-88) and the “Jagonari Asian Women’s Centre” (1984-7) hinged on the ideas of the queer housing cooperative and the women in London’s Asian community who initiated the education center. The group’s approach was to plan and realize buildings not just for, but together with, the users.

Matrix Feminist Design Co-Operative: Making Space: Women and the Man Made Environment, 1984, Image via somethingcurated.com

Sagadin studied architecture, and Matrix is an important role model for her. Analogously to the London-based collective, she explores the dominance of the white heterosexual man, who has for centuries served as the standard and the reference point for architecture and urban planning. With “B-Girls, Go!”, a pink platform topped by an outsize baseball cap, in 2018 she created a sculpture that explicitly invites girls and young women to spend time outdoors chatting, eating, and enjoying themselves. While the title of the work underscores the female counterpart to the “b-boy” of the Hip-Hop movement, the pillar with the silver net on the Rotunda outside the SCHIRN serves up a purely masculine reading of ball games and street culture. The chains with their fine links can be seen not only as accessories used by gang members, but also evoke jewelry and shopping baskets, and thus things that are often attributed to women and non-binary persons. Here, Sagadin plays with very cliched ideas in order to crack open the stereotyped relationships between gender, object, and space, and thus creates the scope for a broader range of users.

The artist’s way of reflecting on built infrastructure with the body and gender in mind can also be seen in the seating that she placed next to the pillar with the net. Anyone sitting down on the bench called “Summer” finds that it is bracketed by plinth elements that resemble breasts or high-heels – attributes and body parts that are usually read as “female” or “queer”. In this way, Sagadin alludes to the female figures that originate in Greek architecture, where they serve as columns supporting temples and gables, the so-called Caryatids. At the same time, she asks who plays this “supporting” role in the design of our cities.

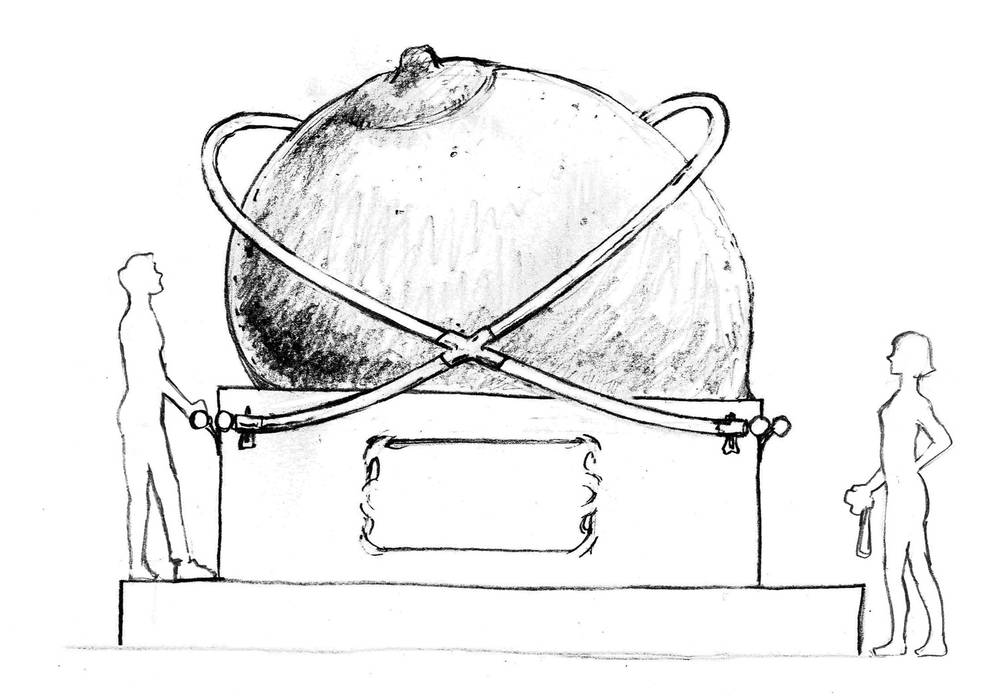

Like artist Lena Henke, who in 2017 designed a monumental sculpture of a breast made of sand for the Highline in New York, Sagadin provokes us into thinking about the space accorded to feeding, care, and reproductive work in the public realm. Henke’s piece, which has not to date been realized owing to the material in question, emphasizes the need to nurture, whilst Sagadin, with the function she gives the bench, points to the fact that those who provide care need to be supported, too. The bench is there to be sat or slept on, for breast-feeding and for sitting and watching children. Activities hitherto assigned mainly to the private sphere, that purported realm of the “housewife”, are thus transposed into the urban space and construed as a criterion for urban planning. The triangular constellation in which the benches are set indicates that the focus here is on both recognition and collective responsibility. Care must be provided not merely by people as individuals but altogether and, as the detachment of the breast from the rest of the body shows, by all genders.

Lena Henke, ascent of a woman, draft for high line plinth, NY, copyright the artist 2017

Feminist urban planning

With her design for a space that favors dialog and community, Sagadin allies with notions of a non-sexist city as promulgated by US architect and urban historian Dolores Hayden and Canadian geographer Leslie Kern. Hayden proposed in 1981 that housing estates be restructured to enable collectivized care-work, while Kern demands that urban spaces and transport be construed over and beyond the white heterosexual nuclear family, efforts be made to reduce social and psychological obstacles, and care-work be better divided up. From her perspective, feminist urban planning also means designing infrastructures for a broad spectrum of relationships. Friendships, or so she explains using the example of her experiences as a white young woman in Toronto, enable us to navigate spaces in the urban realm that we feel are unsafe and make them our own.

The issue of safety and security also makes itself felt in Sagadin’s work. While the risk of violation is inscribed into the bared breast (as if it were an addendum and not used in a manner that conforms to gender) the pillar decorated with a pear references a possible protective measure. Read as a lightbulb, it stands for a (street) lantern – and thus a means often used to free cities of dark corners and other potential “frightening spaces”. Meanwhile, we sometimes fail to remember that light also spells control and possibly exposes marginalized persons to violence.

Dolores Hayden, Image via architecture.yale.edu

Leslie Kern, Image via megaphonemagazine.com

“Luv Birds in toten Winkeln” (Luv Birds in dark nooks and crannies), the title of Sagadin’s ensemble as a whole, questions the equation of visibility with safety and security. The room dividers placed next to the benches and pillars protect doves from the inquisitive eye and thus highlight the extent to which spaces that we cannot immediately grasp visually and are denoted as “dangerous” in everyday life and or in the middle of the road can actually provide protection. Since we can look into these sculptural safe havens from the side, the tension between protective and dangerous space is maintained.

Unlike the kind of urban furniture and buildings that are intended as “defensive architecture”, a way of warding off unintended use in the name of “preventing crime”, Sagadin’s pieces invite us to approach our built environment creatively. Her benches are thus not sub-divided into individual seats in order to prevent the homeless from sleeping on them but offer a broad range of individuals and groups an opportunity to engage in a vast range of activities: to sit, feed, talk, smoke, and seduce, to name but a few. The artist supports the process of appropriating the space she has created by getting artist friends of hers to perform there. What we see manifested here is a zest for experiment – and the willingness to engage with the users and their needs.

The feminist city, or so Kern writes, does not arise on a drawing board and does not obey some “master” plan. Rather, it is based on spaces suffused with possibilities that we have to perceive, seize, and test. Sagadin’s work offers us such spaces and expects us to caringly consider the interests of others who are unable or do not want to take the public limelight.