Born in 1883 as the son of a Bohemian train driver, Rudolf Kalvach was accepted into the arts and craft college attached to the Imperial Austrian Museum for Art and Industry, where he initially attended Alfred Roller’s preparatory classes for figure drawing. He then went on to study painting under Felician von Myrback, and later under Koloman Moser and Carl Otto Czeschka. With teachers like this Rudolf Kalvach found himself directly at the heart of the Viennese Secession, which had reached the peak of its short existence at that time.

Founded in1897 by artists including Gustav Klimt, Koloman Moser and Josef Hoffmann, this society of fine artists had set itself the goal of putting behind it the conservative notion of art that had prevailed up to then in the leading studios of Vienna and creating a new definition. Yet in 1905 an irresolvable conflict developed between the advocates of “Naturalism” and the proponents of a geometric-decorative surface art, with the result that the latter “Stylists”, and they included Gustav Klimt and Kolo Moser, left the Secession.

The Vienna Werkstätte and the Neukunstgruppe

Rudolf Kalvach, with his youth and talent, was hugely inspired by the “Stylists” and in the years shortly after the turn of the century developed his own striking style. In retrospect it was the years between 1903 and 1910 that not only signified a revolution in the Vienna art world, but also marked the high point of the his own creative output: Between 1903 and 1904 his stencil-based work “Kinderspielwaren” (“Children’s Toys”) appeared in "Fläche" – a pamphlet published by Myrbach, Moser, Hoffmann and Roller showing work by their students – and this was followed by his participation in the group exhibition “Die Jungen” (“The Boys”) at the Miethke Gallery in 1906, in which Kalvach exhibited a fanfold with fairy-tale motifs.

Rudolf Kalvach, Leda mit dem Schwan, Postkarte Nr. 107 der Wiener Werkstätte, 1907 © Privatbesitz, Image via leopoldmuseum.org

He had therefore made the shift into public life as an artist and thus Rudolf Kalvach became one of the first and youngest up-and-coming artists to be engaged for the Vienna Werkstätte. Koloman Moser and Josef Hoffmann – Hoffmann also taught at Vienna’s arts and crafts college, the Kunstgewerbeschule – founded the Vienna Werkstätte in 1903 taking their cue from the British Art & Crafts Movement: All the areas of a person’s life, from their work tools to the objects in their home to their jewelry and decoration, should flow into one another to create a stylistically coherent gesamtkunstwerk. High-quality craftsmanship was favored over the “soulless” mass production of factories and thus traditional artistic handcraft was given elevated status.

The woman as a mother or a femme fatale

In the years that followed Kalvach designed 21 postcards and three pictorial broadsheets, and later produced enamel works that were sold in the sales rooms of the Workshop and at festivals. Although he stuck closely to common theme for greetings cards in the designs for his first postcards, in the subsequent prints he gave free rein to his imagination. Fairy-tale characters, mythological creatures, dream sequences, and elements of the surreal and the grotesque found their way onto the cards. One of the best-known postcards, which appeared in 1908, shows the Greek mythological figure Leda with Zeus, who approaches her as a swan and later makes her pregnant. Time and again archetypal female figures appear in Kalvach’s works, be it as mother, as femme fatale or as a childish doll-like figure.

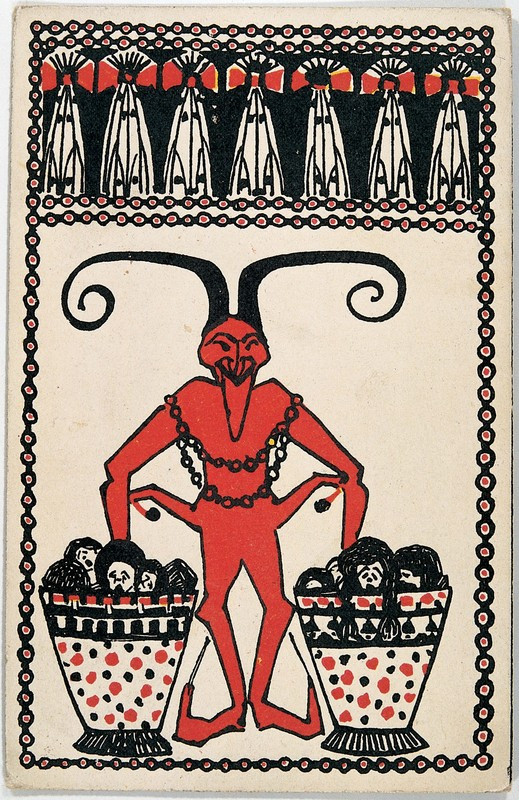

Rudolf Kalvach, Krampus mit Körben, 1908, Image via austria-forum.org

Generally Kalvach uses a black background for his postcards, against which the characters, depicted in primary colors, really stand out – and thus he produces a unique style that sets him apart noticeably from other artists of his time. In his seminars with Carl Otto Czeschka and Bertold Löffler, Kalvach worked intensely on the creation of wood- and linocuts, but it was only later on that he developed a technique of his own: Instead of placing several printing blocks on top of one another to create a multicolored picture, Kalvach printed in black and then added the color as required. For the Art Show in Vienna in 1908 he designed an advertising poster – to this day one of his best known motifs – which was very similar to the print Oskar Kokoschka created for the same occasion.

A footnote in art history

The two images were deemed “twin works” and there was much discussion about who had been inspired by whom or whether the two artists had actually agreed to cooperate with one another beforehand. Kokoschka and Kalvach had met in Alfred Roller’s class at the Kunstgewerbeschule in Vienna, and it is certainly possible that Kokoschka was inspired by the skills of his classmate, who was three years his senior – but this remains a footnote in art history, which these days is generally recounted in such a way as to favor the much better known expressionist Kokoschka.

Rudolf Kalvach, Inspiration, 1907, Image via austria-forum.org

Although Rudolf Kalvach had developed his own style during his studies at Vienna’s Kunstgewerbeschule and was able to market himself with a fair amount of success as a result, he supported his fellow artist Egon Schiele in 1909 in founding the “Neukunstgruppe”, or “New Art Group”, where freshly graduating students from the art school aimed to free themselves from the shackles of the academy in order to adopt a new mode of expression. It was the Secessionists who largely influenced the somewhat teaching structure at the art school, and they tended to favor the floral and ornamental motifs of the Jugendstil, whilst the Neukunstgruppe looked towards more down-to-earth subjects.

A certain melancholy

It is not known exactly when what is probably Rudolf Kalvach’s best-known work – “Trieste Harbor Life” – appeared, because Kalvach never dated his work. The first drafts of the scene, which Kalvach modified again and again in its small details, appeared around 1907; then in 1908 two woodcuts of the harbor scene were exhibited at the Art Show in Vienna, his home city. Trieste, on the other hand, was another city with which he had personal links as his family lived there, so he travelled there frequently and was inspired by the scenes at the port. In contrast to the postcards he created for the Vienna Workshops, which appeared almost “jolly” thanks to their use of primary colors, Trieste Harbor Life conveyed not only the hustle and bustle of the busy port, but also a certain melancholy – an atmosphere that fitted rather well into the perspectives of the “Neukunstgruppe”, which from 1909 onwards made ever more frequent use of subjects such as workers and workplaces, and exhibited Kalvach’s painting, with its Expressionist leanings, in 1909 at Vienna’s Salon Pisko and in 1910 at the Klub Deutscher Künstlerinnen, an association of female German artists in Prague. Gradually Trieste Harbor Life became something of a flagship for Kalvach’s oeuvre.

The artist’s private life was also pervaded by a darkness like that of Trieste Harbor Life: In 1912 he was admitted to a sanatorium due to psychiatric problems, and he was to be confined there until 1915. Even though he did not renounce his artistic work entirely during this time and subsequently recommenced it apparently seamlessly, becoming a member of the Austrian Werkbund, completing his military service and exhibiting at the Viennese Secession’s Werkschau exhibition organized by Egon Schiele, his psychological illness hung over him as a constant threat. In 1921 he was admitted to the Steinhof psychiatric hospital for a second time from which, in 1926, he was transferred to a clinic in the Czech Republic. On March 14, 1932, Rudolf Kalvach died of tuberculosis in the Czech town of Komonosy, leaving behind his wife Marie Klarer and five daughters.