Carol Rama.

A Rebel of Modernity

10/11/2024

10 min reading time

Radical, inventive, modern: the SCHIRN is presenting a major survey exhibition of Carol Rama’s work for the first time in Germany.

Carol Rama, Senza titolo (Maternità) (Untitled [Motherhood]) , 1966, Enamel paint, glue and doll’s eyes on canvas, 90 x 70 cm

Private collection, Turin, © Archivio Carol Rama, Torino, Photo: Gabriele Gaidano

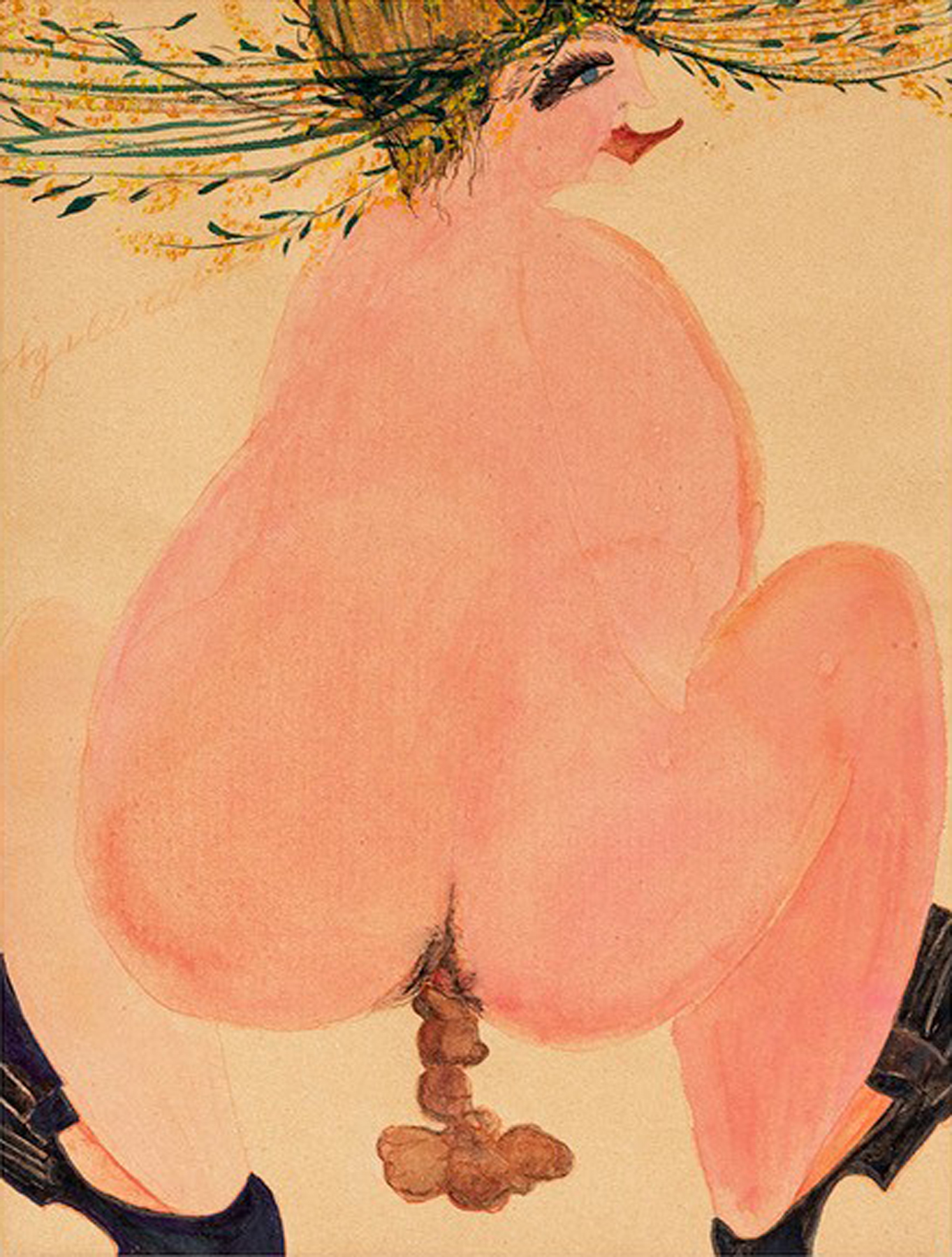

Carol Rama, Marta, 1940, Watercolor, tempera, and colored pencil on paper, 23 × 17.5 cm

Private collection, Turin, © Foto: Pino dell’Aquila

Carol Rama, Senza titolo (Autoritratto) (Self-portrait), 1937, Oil on canvas on wood, 35 × 29 cm

Ursula Hauser Collection, Switzerland, © Archivio Carol Rama, Torino, Foto: Archiv Ursula Hauser Collection

Carol Rama, La linea di sete (The Line of Thirst), 1954, Oil on canvas, 60 × 50 cm

Turin, GAM – Galleria Civica d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, Museo Sperimentale. By courtesy of the Fondazione Torino Musei, © Photo: Studio Fotografico Gonella. Reproduced by permission of the Fondazione Torine Musei

Carol Rama, Presso il pungente promontorio orientale (Near the Sharp Eastern Promontory), 1967, Ink, glue and doll’s eyes on canvas, 36.5 x 24.5 cm

Private collection, © Archivio Carol Rama, Torino, Photo: Roberto Goffi

Carol Rama. Rebellin der Moderne, Ausstellungsansicht, © SCHIRN 2024, Foto: Norbert Miguletz

© SCHIRN 2024, Foto: Norbert Miguletz

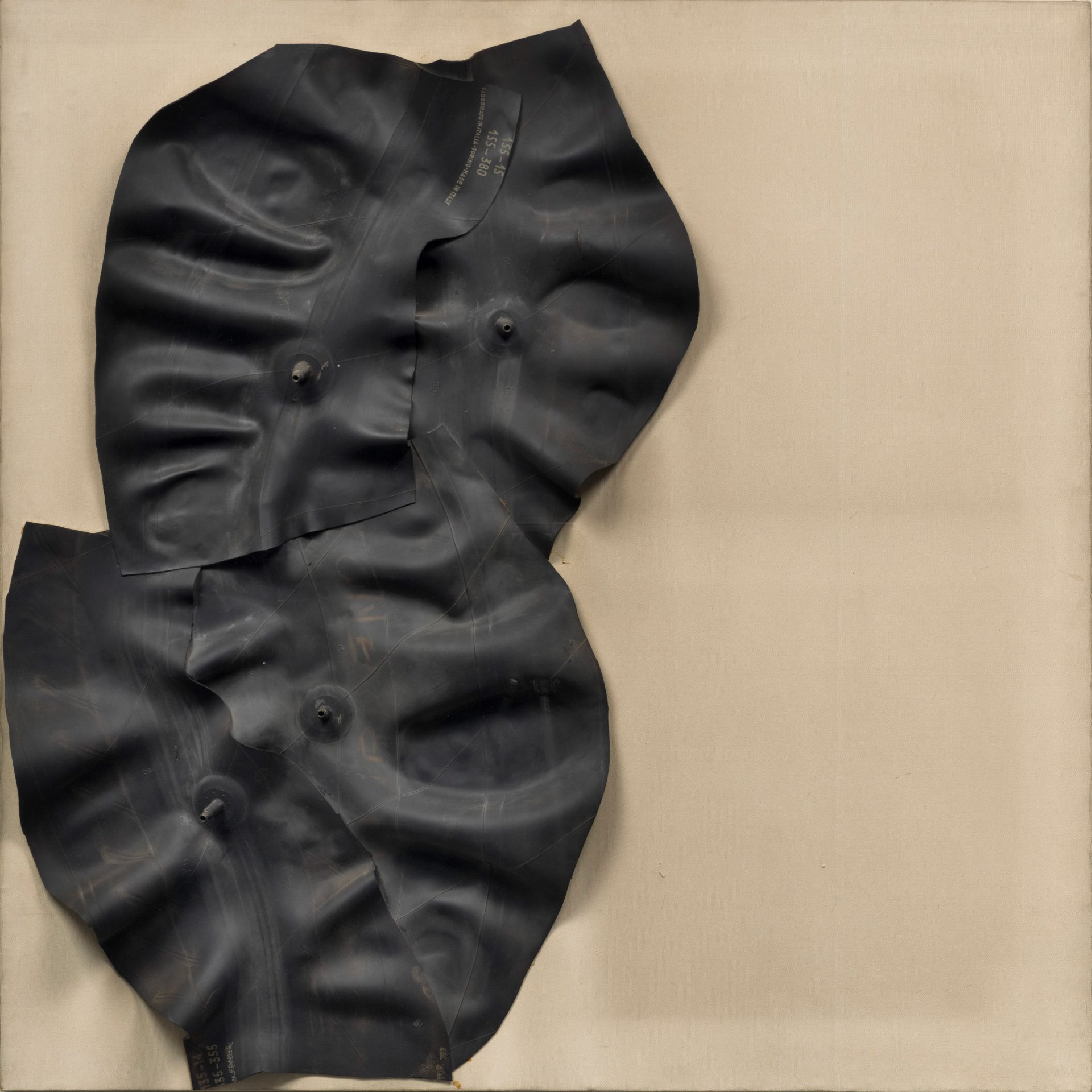

Carol Rama, Autorattristatrice n. 10 (Word play with auto and rattristrare, to sadden), 1970, Inner tubes on canvas, 100 x 100 cm

Ursula Hauser Collection, Switzerland, © Archivio Carol Rama, Torino, Photo: Roman März

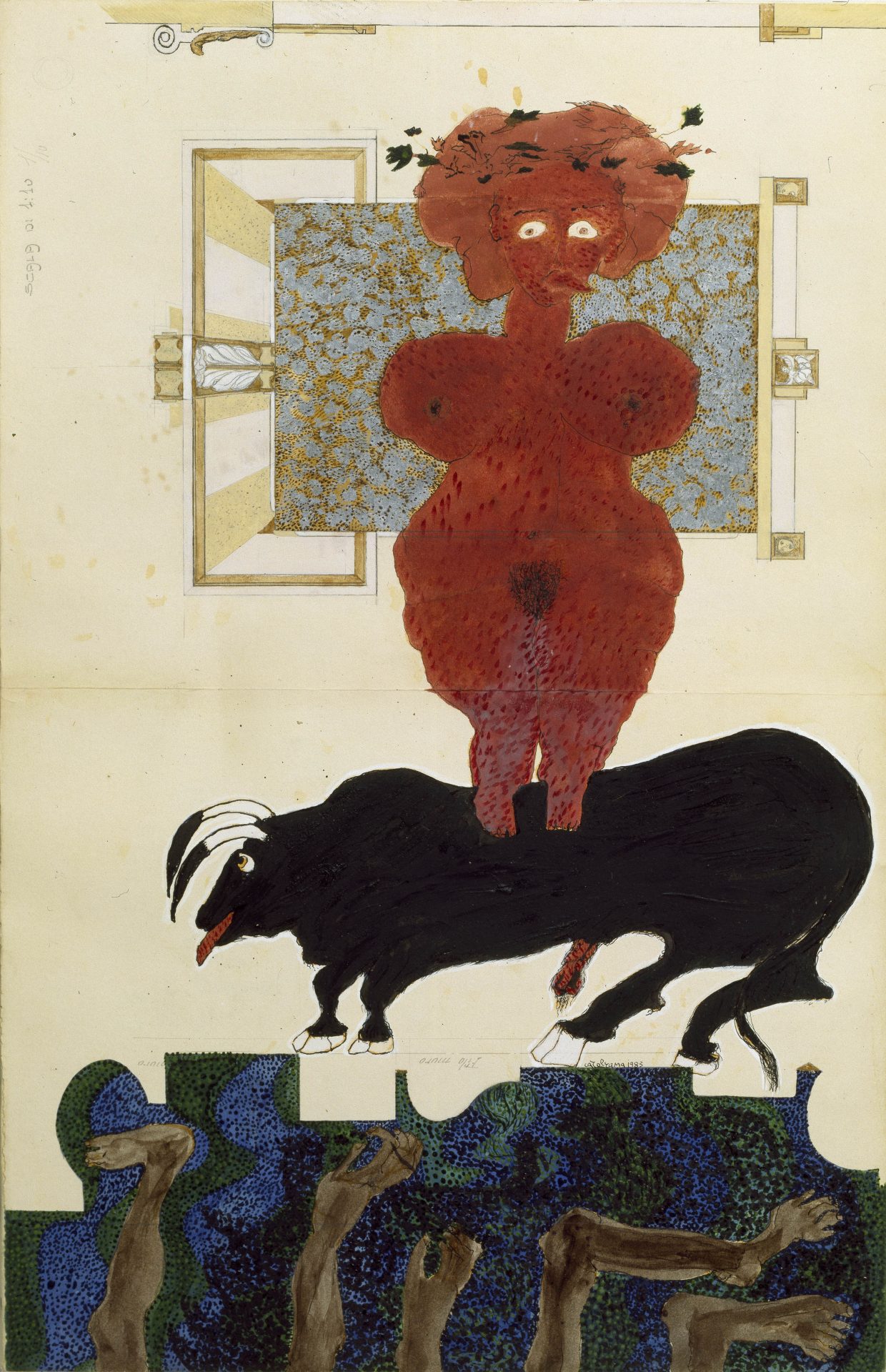

Carol Rama, Lo specchio di Huguette (Huguette’s Mirror), 1983, Mixed media on paper with previous handwriting (architectural drawing), 49.5 × 32 cm

Private Ccollection, © Archivio Carol Rama, Torino, Photo: Pino dell’Aquila