Lyonel Feininger came to painting comparatively late in life, although he had been successful as an illustrator at an early point in his career. Born in New York City in 1871, by his mid-twenties the American was already one of the best-known and most sought-after caricaturists in Berlin, where he had chosen to live from 1888 onwards. There, he had studied at the Königliche Akademie Kunst, where his gift as a caricaturist was noticed. In the epicenter of the media world of the German Reich, Feininger thus attracted great interest from editorial desks but also encountered competition. Yet he endured, something that filled him with pride and a streak of self-satisfaction, but it was a profession that he increasingly started to question after Julia Berg and he became a couple.

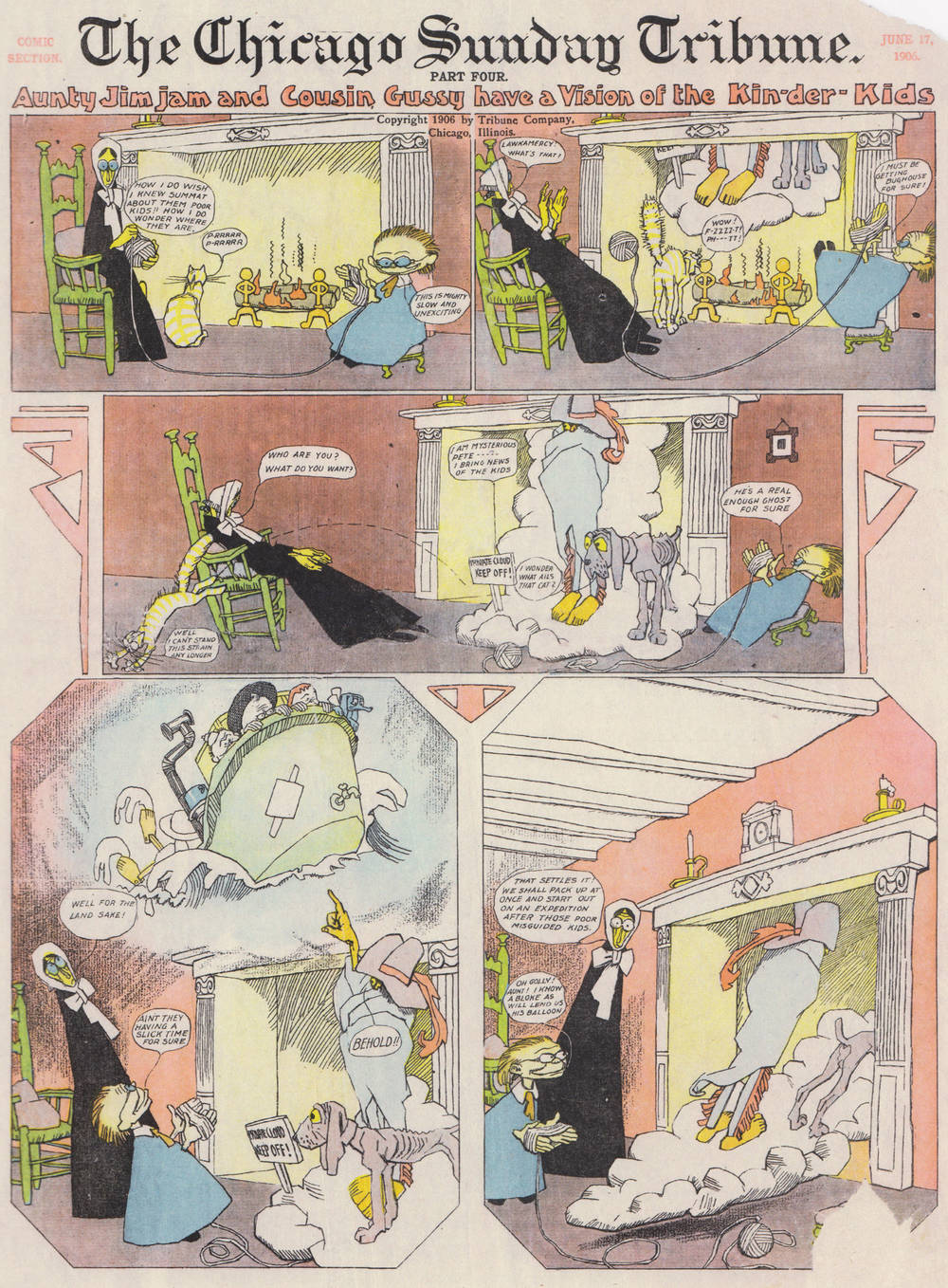

Feininger met Julia, an art student and nine years his junior, in 1905, one year before he received a commission that secured his financial independence for a time: The “Chicago Tribune” hired him to produce two cartoon series, but these went a bit over the heads of the daily’s readership and were thus a disappointment, so they were soon discontinued. Nevertheless, Feininger earned a sufficient amount from the job to be able to afford to move with Julia Berg to Paris without having to fall back on work from his previous German clients. He used this newly achieved freedom to attend painting classes in what was, at the time, the world’s art capital and thus produced his first images. Without Feininger the cartoonist, there would never have been Feininger the painter.

Lyonel Feininger, The Kin-der-kids, Sonntagsseite Chicago Tribune June 17, 1906, private collection, Image via SCHIRN MAG

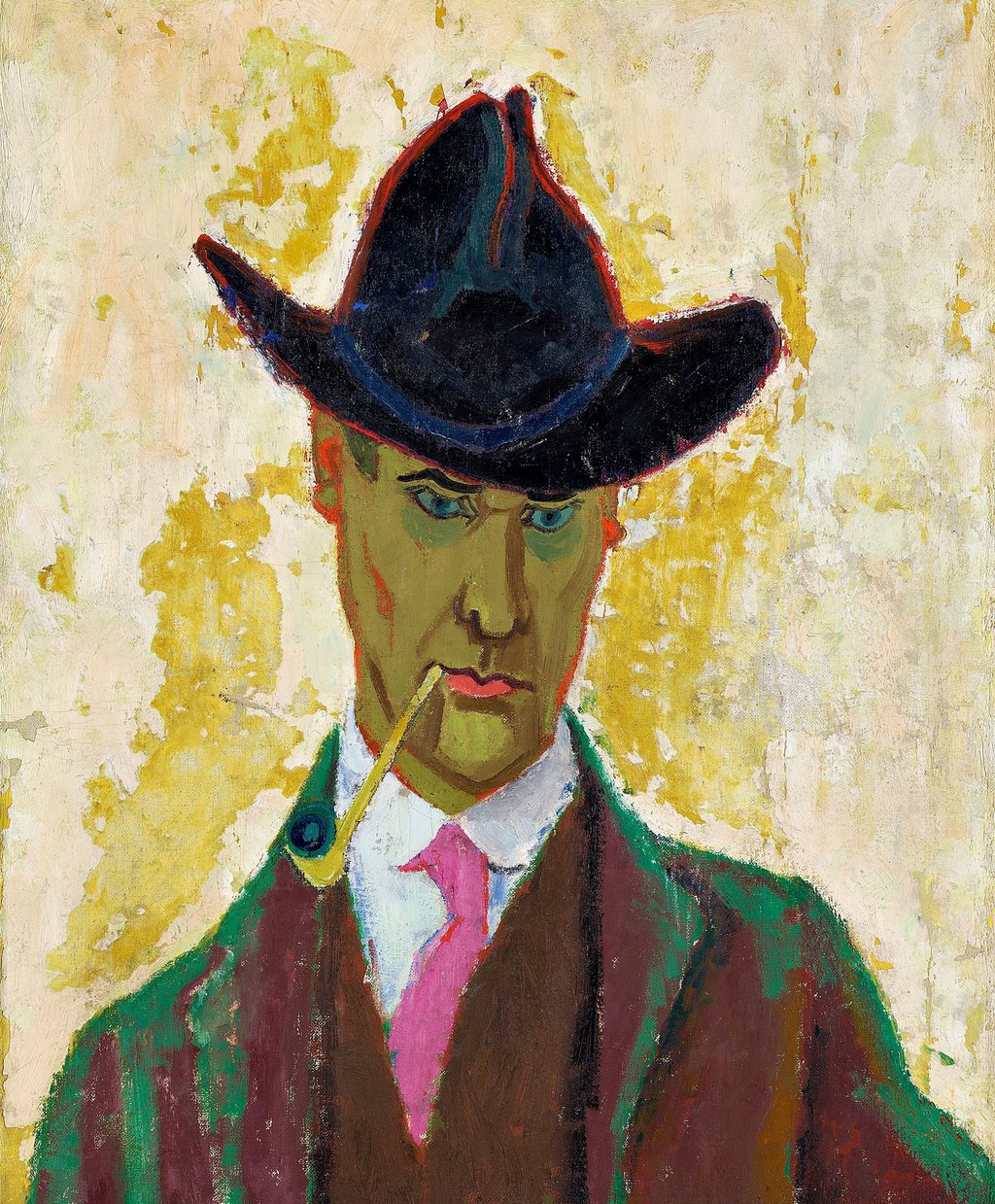

Once the income from America was used up, however, the couple and their son Andreas, who was born in Paris, were forced to return to Berlin. There Lyonel Feininger went back to working as a caricaturist again until, from 1910 onwards, he endeavored to work only as a painter. The Berlin art critics gave short thrift to his pictures, which were still strongly influenced by his caricaturist style and in which Feininger in part also staged himself, for example in the 1907 painting entitled “Der weiße Mann” (The White Man), whose title figure unmistakably reflects his own physiognomy. The disappointment he felt in this early phase of his work as an artist in his own right spawned two characteristics of his later output: first, what he termed “Prismaism” as his very own interpretation of Cubist strategies, which had no relationship whatsoever to his humorous drawings; and second, his eschewal by and large of portraits and self-portraits, as these would have been compared to his popular caricatures of people. In the first two years after the family’s return to Berlin specifically, Feininger concerned himself intensively with drawing his own face, yet today we know only of two self-portraits by him. The earlier of the two survived by pure chance.

The un-adapted American

It was produced in November 1910 at the peak of Feininger’s dissatisfaction with how his career was progressing, namely shortly after he had abandoned drawing for the newspapers but without yet having garnered any success with his art. The painting relied on the shock caused by the color contrast that Feininger typically used at the time and which itself derived from his experience in producing lithographed caricatures: the face in toxic green jars with the salmon pink tie. What is most striking is the clothes and particularly the broad-brimmed hat, which more strongly resembles an American Stetson than any accessory customary in Germany in the early 20th century. In the painting, and far more notably than in his drawn self-portraits, Feininger presents himself much more as an American in Berlin, quite literally a foreign body who is not even granted the favor of striding through a finished background – he hasn’t adapted to life and does not fit in. The sole visible reference to his German surroundings is the thin clay pipe as a leftover from the then caricatured clichés of decadent youth. The man looking at us here is certainly not the father of, by then, a family of three children, but rather someone portrayed as diabolic, yet who appears devilish only in the eye of the beholder.

Lyonel Feininger, Selbstbildnis mit Tonpfeife (Self-portrait with clay pipe), 1910, (photo: Punctum/Bertram Kober © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2021), Image via mz.de

Feininger painted the second self-portrait five years later, and it was to show not only a completely different style but also an utterly new self-confidence. The glowing green of the predecessor is, however, to be found again, this time in the eyes. Triggered by the outbreak of World War I, which, as an American, Feininger viewed from a German nationalist angle, Feininger had been persuaded to return to the field of political caricature. That said, the feeling of duty to his host country was something he felt curbed his own art, which as of 1913 had been received more favorably. His decision once again to discontinue his activities as a caricaturist in the second half of 1915 went hand in hand with the production of this second self-portrait, and thus astonishingly parallels the creation of the first.

The second self-portrait – a German hermit in art?

He evidently felt it an absolute necessity to once again focus on himself, and this attests to the ambivalence of the year 1915. Once again, the result was an unequivocal statement: While the self-portrait of 1910 shows the American standing up for himself in Berlin, that of 1915 asserts Feininger’s changed identity. In the painting, he articulates his wish to be German, having by then spent almost two-thirds of his life in Berlin.

Feininger’s three-quarter view addresses the observer and takes its cue most clearly from German Renaissance portraiture (and above all that of Dürer). Just as apparent is the way the arches refer to Gothic architecture, something at the time considered quite definitively German. However, Feininger’s self-portrait is not a manifesto for a rejection of the society of the day; rather, the facial traits adhere to the principles of the “Prismaism” he launched in 1913. The painting is therefore a prime example of what Alfred H. Barr later identified as a decisive characteristic of Feininger’s work, namely a form of hybrid art that spanned the centuries: “Feininger’s relationship to the German tradition – his fusion of Cubist shapes and the High Romanticist feeling of expanse, distance, the sea, Gothic buildings and churches, etc. – was, to put it metaphorically, a kind of blend of Braque and Caspar David Friedrich, but of course with many original and personal elements.”

Feininger’s self-portrait does more than just present the analytical multi-perspective approach of Cubism, as it offers a synthetic structure that irritates the eye not by the shape but by the colors: a sallow yellowish skin color and the sparkling green of the eyes, which are bereft of pupils. Unlike the 1910 painting, the objective is evidently not to create a self-portrait. Instead, here Feininger seeks to stage a type, which, thanks to the plain smock and the skull cap, has absolutely nothing American about it any longer, conveying instead the sense of a monk, a hermit of art.

A self-portrait suffused with self-irony

In the clearly identifiable study of the head, namely a pastel drawing made in 1908, Feininger had already recorded a similarly skeptical gaze, but seven years later he presents himself as unapproachable. The pose intimates the pride of a maverick, yet Feininger himself, when putting it on show two years after he completed it, spoke of it as the opposite of “a beautiful, ideal self-portrait”. He asked: “So what should be preferred? Self-irony, most definitely. The incognito of a ‘mask’ (like 200 years ago when there was still culture in Europe) in the face of an inquisitive crowd.”

What Feininger did with the painting was, in other words, to transpose the game of masks in the “pictures of a masquerade” (his term for his paintings that drew on his caricatures) onto a monumental portrait format – this was, as it were, the climax and completion of his work as a caricaturist, realized here in a portrait of himself, in other words at his own expense. It is no surprise that he really enjoyed the irritation the portrait caused among viewers of the day. However, that enjoyment resembles Kafka’s laughter when he read from his own works, whose self-ironical quality other readers overlooked and understood as an expression of the deepest despair.