Hans Haacke in New York

01/17/2025

12 min reading time

Hans Haacke has lived and worked in New York City since 1965. Reason enough to take a closer look at his relationship with the “Big Apple”: From his influence on New York art institutions and galleries to his teaching at Cooper Union.

Lorem Ipsum

Shortly after the “MoMA Poll”, Haacke faced more trouble over his institutional critique when his solo exhibition at the Guggenheim museum was canceled over “Shapolsky et al. Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, A Real Time Social System, as of May 1, 1971”, a piece exposing the machinations behind real-estate holdings owned by New York’s most famous slum-lords Harry Shapolsky and others. Thomas Messer, then director at the Guggenheim, canceled Haacke’s show only six weeks before opening because the artist refused to get censored by the museum and take out the three related artworks as requested by Messer.

Since then, Hans Haacke has not left the path of institutional criticism, even though it has cost him dearly: It would be around 15 years before the artist would be exhibited in a US museum again.

Lorem Ipsum

Paula Cooper, who founded the Paula Cooper Gallery in 1968, remembers meeting Haacke for the first time already in 1969 “when he came to install his work for “Number 7”, a group show curated by Lucy Lippard in my first gallery on the third floor at 96 Prince Street. I vividly remember his piece–an environmental work on a pedestal that used a fan to redirect the flow of air. He was showing with Howard Wise Gallery at the time, and I knew of him but did not yet know him personally.”

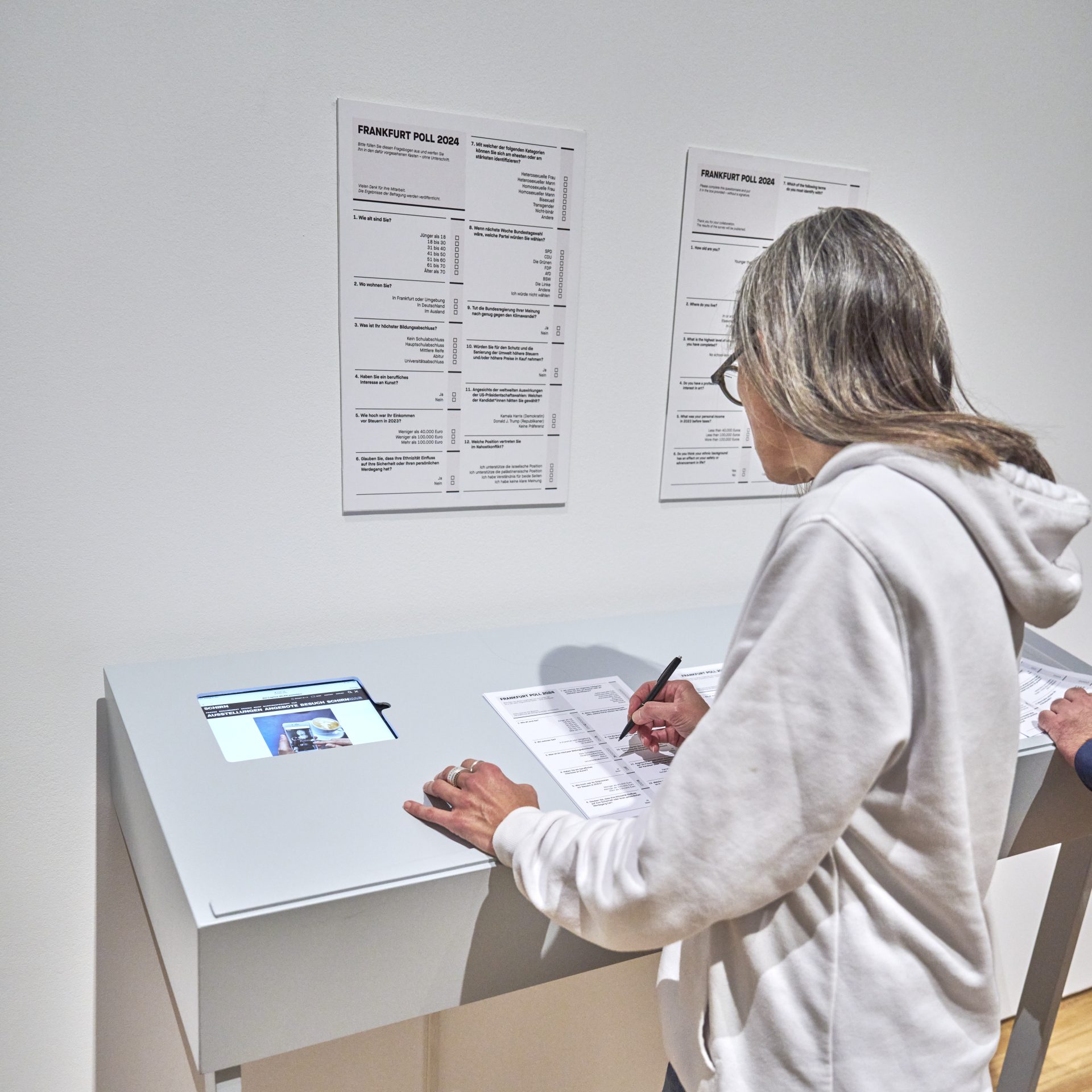

She and Haacke crossed path multiple times while travelling to visit the big European group shows like the documenta in Kassel where Haacke presented his work on more than one occasion, including in documenta 5 (1972) where he put together the “Documenta-Besucherprofil”, a questionnaire with 10 demographic and 10 opinion based questions around current socio-political problems. Questions included “Are you in favor of abortion?” or “Would you be willing to pay higher taxes and higher prices to protect and restore our environment?” Cooper recalls that she “was very impressed by the range of his art, from the pieces exploring natural systems to those examining social, political and economic structures; the work was sometimes ephemeral and sometimes very physically present.”

Haacke & Cooper Union

Aside from showing his art at New York galleries, Hans Haacke also started a teaching position at Cooper Union in 1967 which he held for 35 years until 2002. The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art or just short Cooper Union was founded in 1859 by Peter Cooper as a private college based on a radical new model for higher education in the US: to be “open and free for all.” Education per Cooper should be accessible to everyone who is qualified disregarding gender, race, religion, wealth or status – a model the school has held onto with some exceptions ever since. Appointing Hans Haacke into faculty seems more than just fitting, it feels like a match made in heaven.

With limited spaces came fierce competition: photographer and conceptual artist Kevin Clarke who studied under Haacke from 1973 to 1976 remembers “Cooper Union as an elite school and the students were considered especially capable. Everyone received a full scholarship, which was unique in the USA. This made for competition.” To him Haacke “had a casual teaching style based on his knowledge of contemporary art with an emphasis on Conceptual Art and art and social responsibility. Other sculpture professors were more interested in minimalism or romantic and spiritual threads in art history, Hans represented a stricter, certainly German philosophy. German art in the 70’s was different from, say, French or Italian or the NY or Chicago Schools of Art […] NYC art students were reading The Fox, October, Wittgenstein, Levi-Strauss, structural linguistics, encouraged by Professor Haacke.”

Lorem Ipsum

ART CLUB2000 remembers: “Hans was a great teacher! […] He introduced us to Institutional Critique, in how he directed our thinking in class and through our studying his work at the time. It may have been because of one of the show announcements he posted that we went to see Andrea Fraser’s performance ‘May I Help You’ at American Fine Arts, Co., which was pivotal in how we started to think about making art. ART CLUB2000 may not have existed had it not been for Hans.”

Aside from introducing alternative thinkers to his students and inviting artists to his class room like Mark Dion, Lorna Simpson, Dorothea Rockbourne, or Fred Wilson, “Haacke also stopped giving assignments after second year, which forced his students to find their own voice as a critical part of the creative process,” the collective adds. “Haacke as a professor not only taught technical skills and artistic methods but also instilled a sense of social responsibility, critical thinking, and courage to question the status quo.” They remember him as a “big presence but quiet, thoughtful. He usually rode an old-style city bike to school. We would see him cycling around the Lower East Side.”