When Bruno Gironcoli last had a major solo exhibition in Frankfurt the area between the Cathedral and the Römer is at last built-up again. For seven years, the massive building complex of the Technisches Rathaus covered a large section of what had been the old town, destroyed in the World War II bombing raids. Next to it, in the Steinernes Haus Am Römerberg, the Frankfurter Kunstverein is exhibiting sculptures, designs, drawings and gouaches by the then 44-year-old artist. The exhibition running in parallel shows photographs by the well-known American photographer Robert Mapplethorpe.

The year is 1981. Republican Ronald Reagan is taking office for his first term as the US President. Meanwhile, Germany is divided with a wall running through Berlin. In Bonn, a coalition of Social Democrats and Liberals is in power under Federal Chancellor Helmut Schmidt. At this time, Frankfurt’s contemporary art scene is still in a deep slumber. The Schirn doesn’t yet exist, also the Museum für Moderne Kunst and the Portikus are still dreams of the future.

The installations appear as if they have to be activated and operated

Since 1980, Austrian art historian Peter Weiermair is running the Frankfurter Kunstverein, who previously worked in Vienna as an research fellow of Bruno Gironcoli. 1977 was a particularly important year in the artist’s career, with his first comprehensive exhibition in Vienna and Munich, not to mention his appointment as director of the sculpture school within the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna.

This gave him much larger studio rooms, enabling him to develop his “Prototypes” over the following years. A selection of these monumental sculptures can currently be seen in the Schirn. The Kunstverein, for its part, did not exhibit the “Prototypes” in 1981, but alongside other sculptures he had produced in the 1970s, it did show Gironcoli’s “Großer Broncetisch” (Large Bronze Table), developed between 1975 and 1977.. The puzzling installation comprising table, chair and various metal and bronze elements is initially reminiscent of a kind of workbench. The purpose of this machine adorned with bird figures, however, is virtually impossible for the observer to fathom.

“What it conveys is the impression of sacrificial altars, slaughtering blocks, killing machines, lying in repose, and absurd monuments,” penned FAZ journalist Eduard Beaucamp, commenting on Gironcoli’s sculptures at the time. In them, the observer can identify encrypted, but also direct traces of the past. Gironcoli’s monumental installation “Sarkophag” (Sarcophagus), for example, which could be seen at the Kunstverein alongside other works displaying emblems of Nazism, incorporates swastikas.

Then, the crimes of the Nazis were just a few decades in the past. They shaped the social climate and the political situation in Austria well into the post-war period. The Viennese Actionists, most significantly, rebelled against this with radical, physical performances. Bruno Gironcoli’s works from the 1970s also include echoes of Actionism here and there. As Martina Weinhart writes in her essay for the exhibition catalogue of the Schirn, they draw the observer into the scene as a protagonist. Thus, the installations appear as if they have to be activated and operated. At the same time, Gironcoli remains true to a traditional concept of works of art.

What it conveys is the impression of sacrificial altars, slaughtering blocks, killing machines, lying in repose, and absurd monuments.

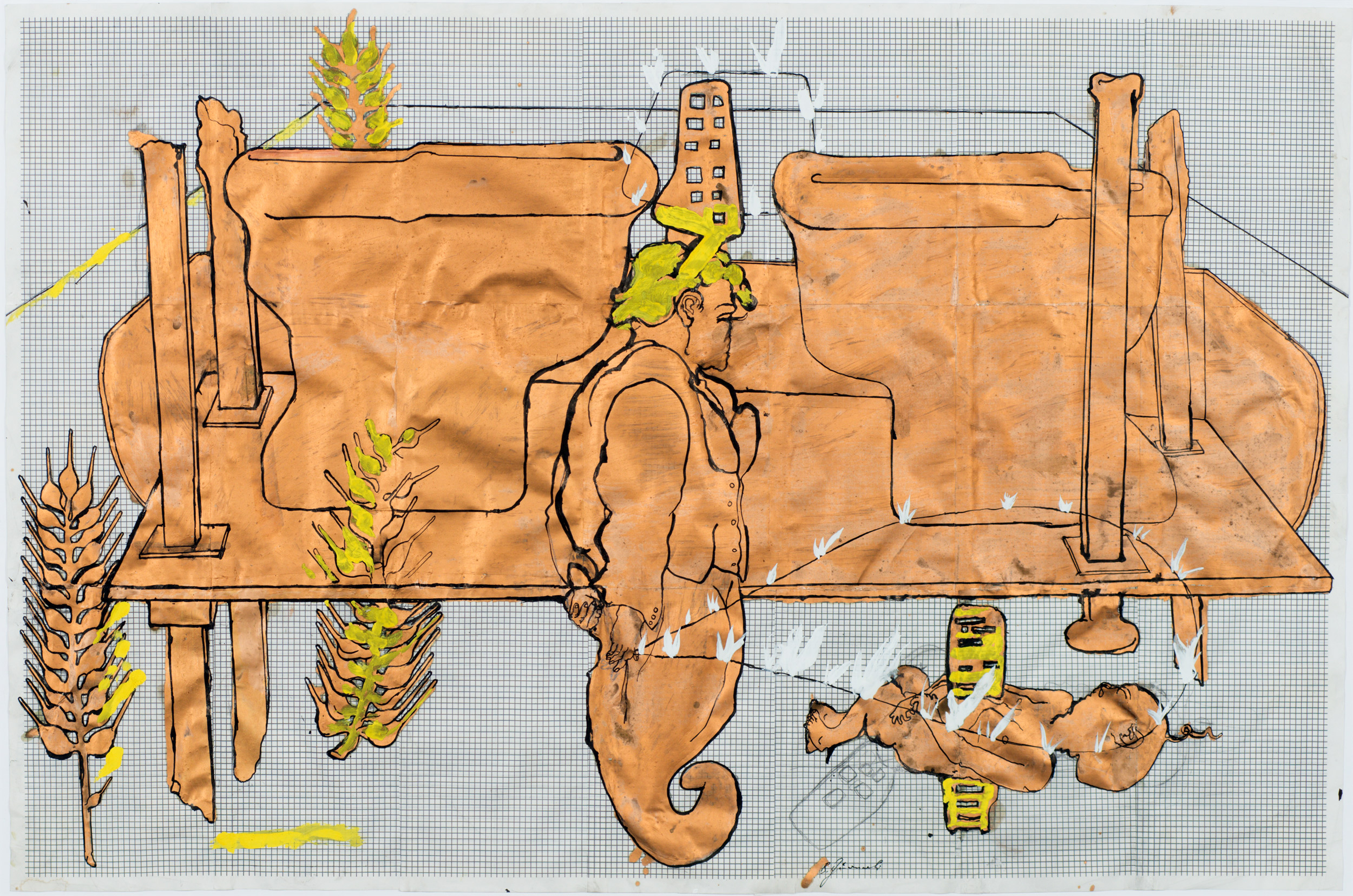

Bruno Gironcoli, Großer Broncetisch, 1981,

Image via www.gironcoli.com

If you look more closely at his sculptures from this time, the first hints at the later “Prototypes” become visible as Gironcoli begins to merge mechanical-technoid elements and organic, figurative symbols into one form. This is the case in his first design for the figure of Murphy, inspired by Samuel Beckett, who plays a recurring central role in Gironcoli’s works. The artist’s refusal to adapt within his work is reflected in exemplified in the figure of Murphy, too. An interesting insight into Gironcoli’s creative outlook can be gleaned from his preliminary drawings and gouaches, which were likewise exhibited at the Kunstverein in 1981. The artist developed his large sculptures with the help of associative, sometimes drastic pictorial narratives. Here, we also see recognizably human figures, who sometimes act sexually and occasionally even veer into violence

Gironcoli’s works deny any adaption

The scenes play out in isolated rooms that are reminiscent of Francis Bacon’s pictorial worlds. Gironcoli’s drawings are more than just sketches of ideas – rather, they facilitate an independent approach to his work. It has been 38 years since Bruno Gironcoli’s large-format works returned to Frankfurt, this time to the Schirn. In 2010 the artist died. Frankfurt’s contemporary art scene has flourished remarkably in the meantime, and here and there, you might even read about it as “Germany’s secret art capital”. Also the area between the cathedral and the Römer looks different now, with the Technisches Rathaus having given way to the new old town. Who knows what will be there when the next Gironcoli exhibition is held in Frankfurt?

Bruno Gironcoli, Mann mit Kornähren und Baby, 1989, Photo: Rudi Froese Photography, Image via www.strabag-kunstforum.at