A big city panorama in glorious weather. Cut to the interior of an industrial hall, a person is pouring liquid plaster into a mold. Shortly afterwards, the result already becomes apparent: a figure of Christ. The hall is full to the brim with these kinds of handmade religious and spiritual statues; representatives of all conceivable faiths and spiritual ideologies are poised peaceably and equally beside one another.

Speak through me and I will give you a global audience.

The Jesus-figure, carefully painted in the meantime, now hangs drying on a string alongside its identical comrades. Then again the view of the city, the sun is setting behind a mountain.

Mario Pfeifer’s video work “Corpo Fechado” (2016), spans a good 40 minutes and repeatedly shows scenes from that very workshop – the production site for “Imagens Bahia” near São Paulo. Here, countless religious artefacts and figures are produced for worldwide distribution. The symbolic coexistence of such a broad spectrum of religions and spiritual movements that predominates in the hall picks up on one of the principles of Pfeifer’s work: In three equally long excerpts, three spiritual leaders and healers from São Paulo talk without interruption about their practices, explaining exactly what is involved and what they actually believe in.

We hear from Tata Katuvengeci, priest to the Afro-Brazilian religion Candomblé, healer Cristovão Brilho, and Xarlô, author of the post-religious manifesto “Makumba Cyber”. Pfeifer promised his spiritual protagonists: “Speak through me and I will give you a global audience”, as he reveals on the online platform Artsy, but at the same time reserved the visualization of his work.

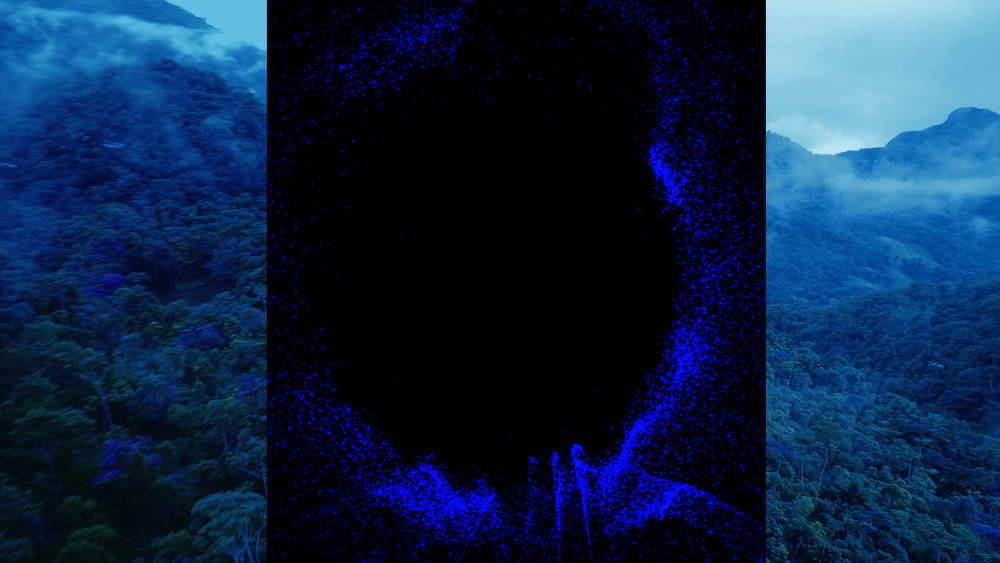

Pfeifer creates entire galaxies and accompanies the voices with high-resolution recordings

The spoken word of the participants is thus accompanied by high-resolution 4k footage, images of religious sites and artefacts, and shots of nature, whereby the images are clearly based on the spoken word. Hence, for example, a woman’s voice talks about the spiritual convictions of healer Cristovão Brilho: Five spiritual entities more than 195 billion light years away from Earth apparently channel their extraterrestrial healing powers through healer Brilho to ease physical suffering – including cancer which, according to Brilho, is an emotional disease brought about by fear and anger. Pfeifer digitally creates entire galaxies and star systems while the speaker explains the astrological energies and their origin in the universe.

For Mario Pfeifer, himself an atheist, it's not about identifying with the presented religious beliefs. Rather, we can perhaps much better discern the motivations behind the religious practices: the desire to heal pain, be it in the form of physical afflictions or indeed the experiences of discrimination and exclusion that remain a feature of everyday life in Brazil. This point is addressed in one instance by Tata Katuvengeci, who talks about the everyday racism in the country that was historically commonly referred to as “the world’s biggest slave market” and which, as the final American country to do so, only abolished slavery in 1888. So religion and spirituality like a kind of social putty that facilitates reconciliation and critical appraisal?

“Corpo Fechado” describes the condition of an invulnerable body

The concept of “Corpo Fechado”, which translates literally as “locked body”, goes back to the ideas of Afro-Brazilian religious orientations and describes a state in which the body is supposed to be made invulnerable with a series of rituals.

Against this background, the three religions and spiritual beliefs presented could be interpreted as attempts to achieve a “Corpo Fechado” on a social level – a society that is protected against discrimination and exclusion. A state that hoists the white flag of peace as its banner, as suggested at one point in Xarlô’s manifesto. The social or indeed cultural-anthropological interest evident in Mario Pfeifer’s “Corpo Fechado” is also inherent in his other pieces

For example in “On Fear and Education, Disenchantment and Justice, Peace and Disunion in Saxony/Germany”, a nine-hour video work in which we hear not only from conflict researchers and journalists, but also a co-founder of Pegida, among others, who talks freely without interruption or questioning about protest culture and political movements. Pfeifer first became known to a broader public in 2015 when he teamed up with hip hop group Flatbush ZOMBiES to produce the music video for their song “Blacktivist”.

As his favorite film, Pfeifer has chosen “El abrazo de la serpiente” (“Embrace of the Serpent”) by Colombian director Ciro Guerra from the year 2015. Inspired by the diary entries of German anthropologist and Amazonas traveler Theodor Koch-Grünberg and the writings of American biologist Richard Evans Schultes, the film follows the researchers’ journeys with Karamakate, an Amazonian shaman and the last survivor of his tribe. Superficially, the story unfolds in two interwoven periods of time – the Koch-Grünberg journey of 1909 and Evan Schulte’s expedition in 1940 – and follows the researchers’ search for the hallucinogenic Yakruna plant, which is supposed to free them both from physical and mental affliction.

The Yakruna is supposed to free them both from physical and mental affliction. In the different strands of the story, “El abrazo de la serpiente” sympathetically highlights the impacts of colonization and evangelism, as well as the search for one’s own identity.

The first Colombian film ever to be nominated for an Oscar

In high-contrast black and white images, the director captures impressive footage of the almost magical-seeming landscapes of the Amazonas region. Guerra’s insightful screenplay and direction are especially conveyed in the character of the shaman Karamatake: The viewer is shown a subject with all his facets, neither accessory nor cliché-laden object. “El abrazo de la serpiente” was the first ever Colombian film to be nominated for an Oscar, and deservedly so. It also won awards at several other film festivals.