Freedom costs peanuts

11/12/2024

8 min reading time

Hans Haacke responded immediately in 1990 to the fall of the Berlin Wall and turned a watchtower into art.

Symbols of East and West in Haacke’s “Watchtower” project

This is also the context in which we should read Haacke’s contribution. The tower symbolized the East, the star the West. The montage posed various questions: How can the different systems unite? Can individual elements be combined? Or will misunderstandings arise and likewise unintentional overlaps? The positioning of the star on top suggests the prophecy that the economic (control) system will replace the prior political one.

In the summer of 1990, Haacke’s “Watchtower” project highlighted the predominant position of the West and the capitalization of the East. In fact, he outfitted the tower with a symbol of consumerism precisely at the very moment the Wall itself became a consumer commodity. On June 20, 1990, Sotheby’s in Monte Carlo auctioned off 81 individual sections of the Wall for up to 30,000 Deutschmarks each, with the total proceedings coming to two million Deutschmarks.

The star specifically points to the activities of the Daimler-Benz corporation in Berlin in 1990: In the summer of that year, the company had acquired prime real estate on Potsdamer Platz for a tenth of the estimated value. This was a matter of public debate as early as 1990, and Haacke’s “Watchtower” locked into this debate, criticizing the company and the overhasty actions of the Berlin municipal government. Two years later, the corporation had to make a subsequent payment of 33.8 million euros, as the monopolies commission had declared that the purchase price broke the law. An ironic advertising column, therefore, for Daimler-Benz: This interpretation of the watchtower is supported by the slogans “Kunst bleibt Kunst” and “Bereit sein ist alles”, which drew on two of the corporation’s then ad slogans and brought to mind the East German boy-scout motto.

Finally, the star clearly alluded to another Berlin building: On the roof of the Europa Center at the top of Kurfürstendamm, a corresponding, if far larger, Mercedes star still rotates to this day. During the days of the divided city, it symbolically ensured West Berlin participated in West Germany’s flourishing economy.

“The banner reinforces our bond with all migrants and displaced persons who at present are exposed to virulent xenophobia, racism, and life-threatening religious conflicts in many countries in the world.”

Hans Haacke

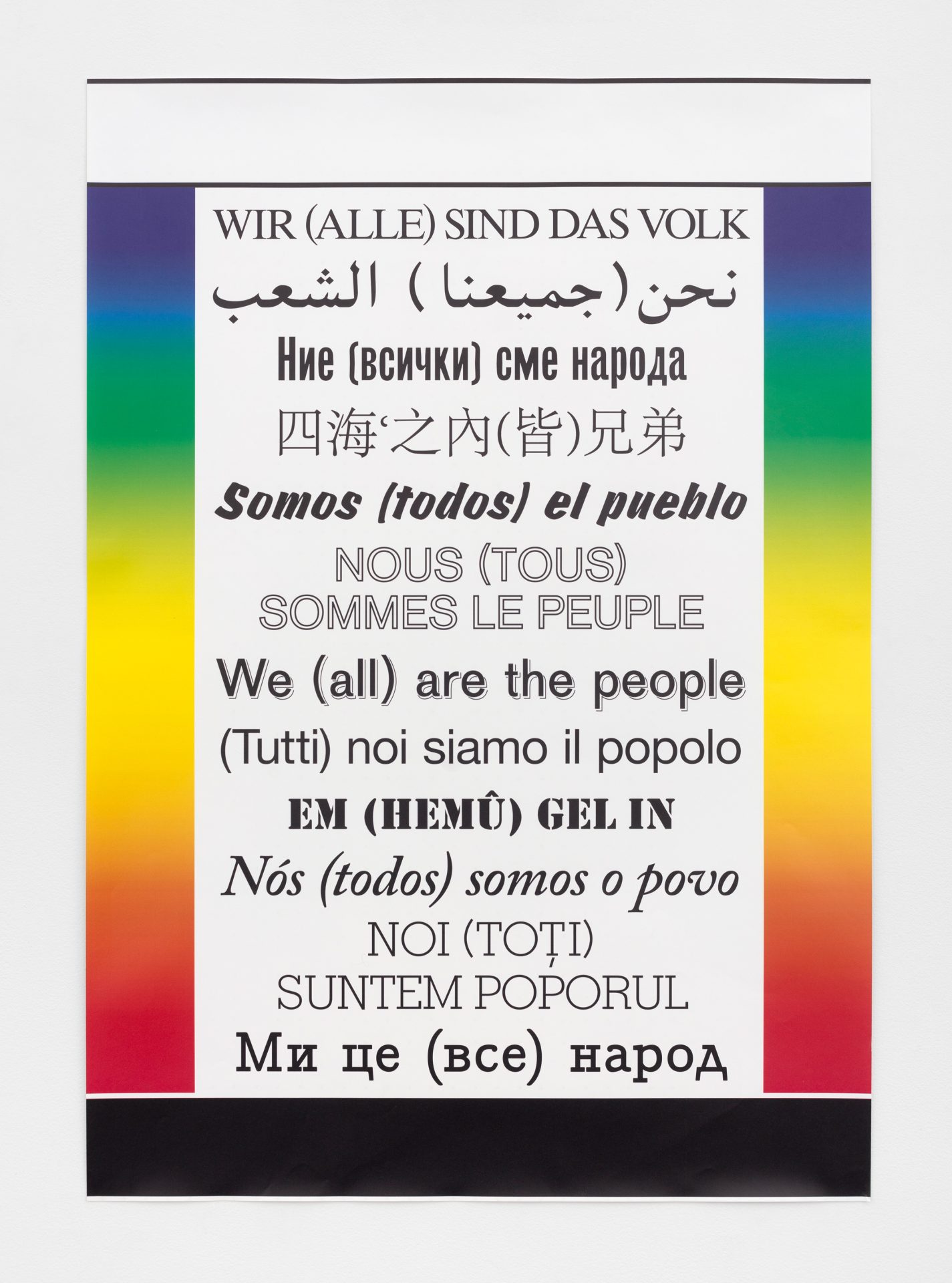

“We (all) are the people”

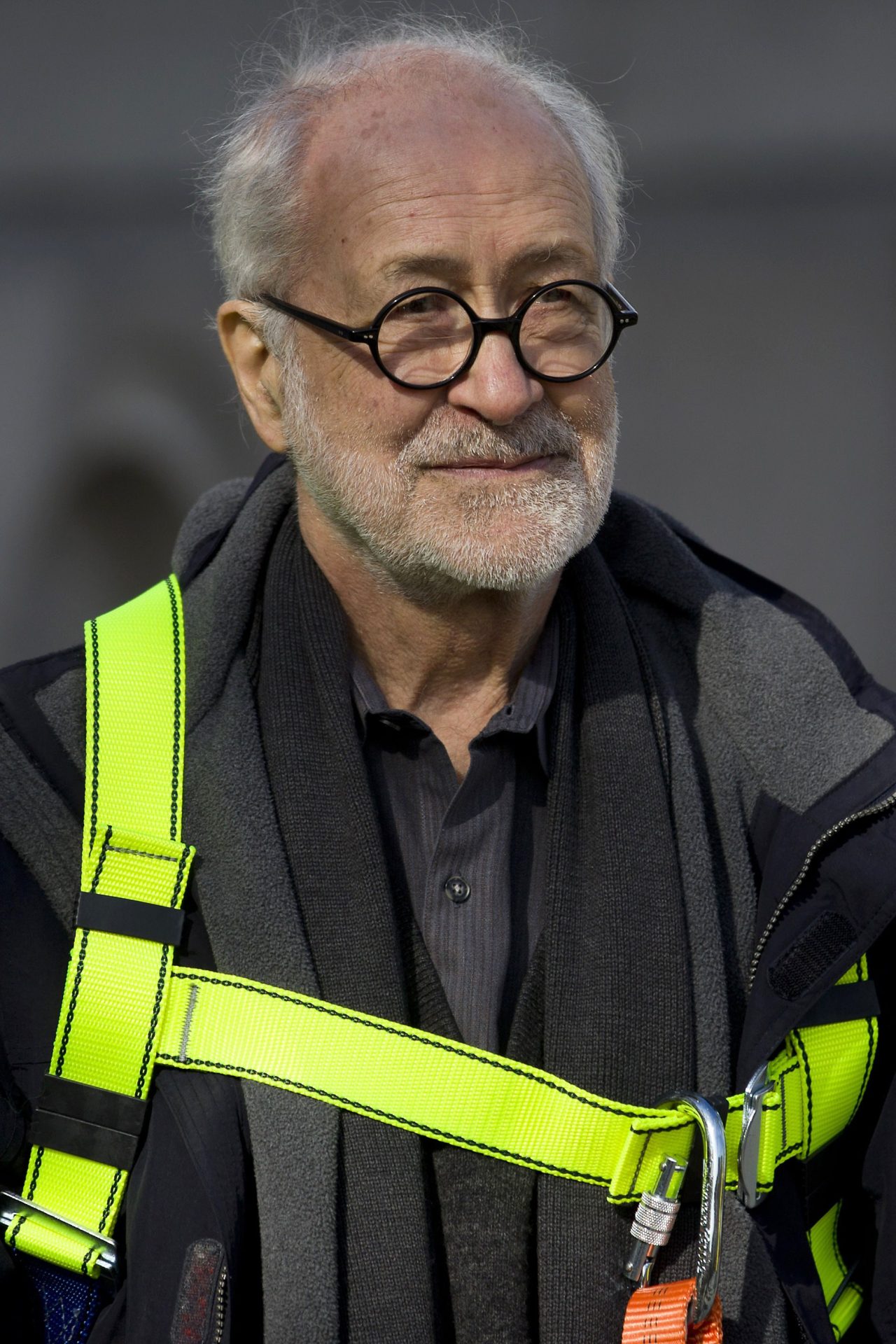

September 2016 saw me fly to New York to meet Hans Haacke and interview him. Born in 1936 in Cologne, he studied in Kassel, which was part of the “Zonenrandgebiet”, or zonal border, 30 kilometers from the border with East Germany. Since 1965 he has lived in the USA, but reads “Der Spiegel” magazine every week and remains in close contact with friends and colleagues. We met again in Athens for the opening of documenta 14 in spring 2017. For this show, he had returned to his idea for Leipzig: A banner and 10,000 posters were illegally glued to walls in Athens, on street corners and in public spaces. The poster boasted 12 lines of “We (all) are the people”, written black on white in various fonts and languages. In Kassel, the theme unsettled things, appearing on countless billboards and ad spaces.

The choice of languages reflected the respective percentage of migrants and displaced persons in Greece and in Germany, Haacke explained: “The banner reinforces our bond with all migrants and displaced persons who at present are exposed to virulent xenophobia, racism, and life-threatening religious conflicts in many countries in the world.” The rainbow that framed the block of text gave the statement an appealing touch and is reminiscent of the rainbow flag, which stands for the advent of the new, for peace, and for the acceptance of different, individual ways of life.

Since documenta 14, “Wir (alle) sind das Volk” has been seen on banners, posters, and postcards in Brussels, Ghent, New York, Bratislava, and Ramallah, not to mention in Leipzig, Zwickau, Halle, Dresden, Chemnitz, Stuttgart, Berlin, and Weimar. As part of the Hans Haacke retrospective at the SCHIRN, the decentral piece is now also present in Frankfurt’s urban space.

Where Haacke’s Mercedes star illuminated the no-man’s land killing zone back in 1990, in recent years a new residential district has arisen. The brochure advertising the new condominiums for sale highlights the site’s history: “The Luisenpark Berlin-Mitte quarter is prestigious, urban, and truly historical, since the Berlin Wall ran exactly along Stallschreiberstrasse, which borders the district.”