The world’s superfluous elements

08/13/2024

7 min reading time

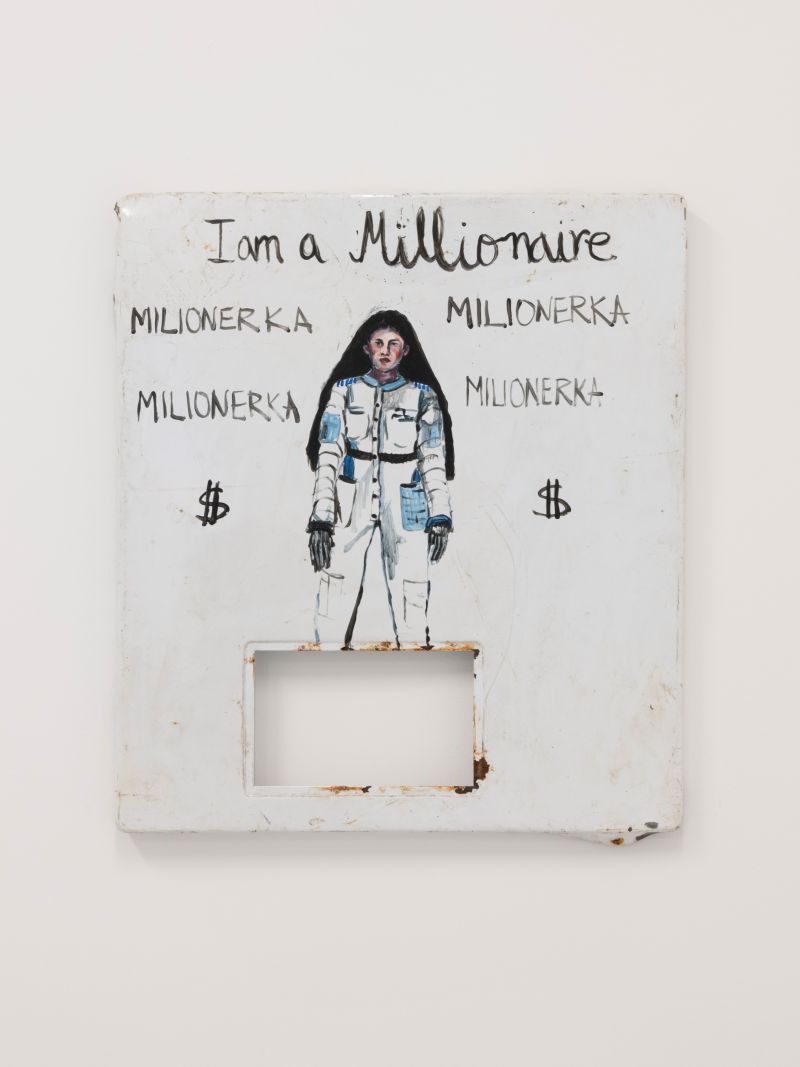

Selma Selman’s art often revolves around recycling, something that places her in a long lineage of artistic transformations

Futurists of the 21st century

There is too much of everything in the world and yet it is never enough. Too little potable water, too little clean air, too much trash. That is a problem, so much so that it is shifted around the world, often along old colonial lines of power. Electronic scrap ends up on toxic dumps in Africa where raw materials are harvested in conditions that are hazardous to workers’ health. From a global viewpoint, recycling (which the Global North sees as the basis of an environmentally conscious economy) is a pretty dirty business: No less waste is produced but it is less visible. The superfluous quantities of everything gets repressed and the old imbalance of power between the center and the fringes is repeated. And as Selman once put it, the Romany people have been working in the scrap trade for more than 100 years now “in order to survive as an oppressed minority in modern Western society”. This is the source of their knowledge about the durability and reusability of materials. “In my opinion, in the 21st century the Romany people are the planet’s leading social, ecological and technological futurists.”

“In my opinion, in the 21st century the Romany people are the planet’s leading social, ecological and technological futurists.”

Selma Selman