Grand Theatrics

11/21/2024

7 min reading time

Why diverse teams alone will not be enough to change systems.

Lorem Ipsum

Progressive institutions really are trying to do better. The aim is to implement diversity, safe spaces, transparency – in order to create a surrounding that is able to leave racism, sexism, queerphobia and violent behavior in the past and move towards a happier, brighter future built on togetherness. Institutions that understand themselves as relevant places for art and culture have long understood that the white-Man-Tyrant type of person that can get away with everything simply because he is or rather must be a genius – is no longer the pick to lead any project or House into glory.

All efforts go into finding a different type of leader to hand the power to. Rarely – we see the effort to challenge and question existing concepts of power itself.

And so, despite all good will, almost all creative projects end up in tears anyway, no matter how genuinely everyone involved has committed to deconstruct old traditions and combat toxic work environments.

Those institutions open to bring queerfeminist topics and artists onto their stages and into their exhibition halls are often the ones who also hire artists that might not come from an academic background or classical training, but who use aesthetics and artforms emerging from subcultures and aim to overwrite dominant societal narratives. Often, exactly these projects reach great success. Whenever the art presented to an audience includes multiple diverse perspectives, the audience itself multiplies, becomes more diverse and therefore – larger.

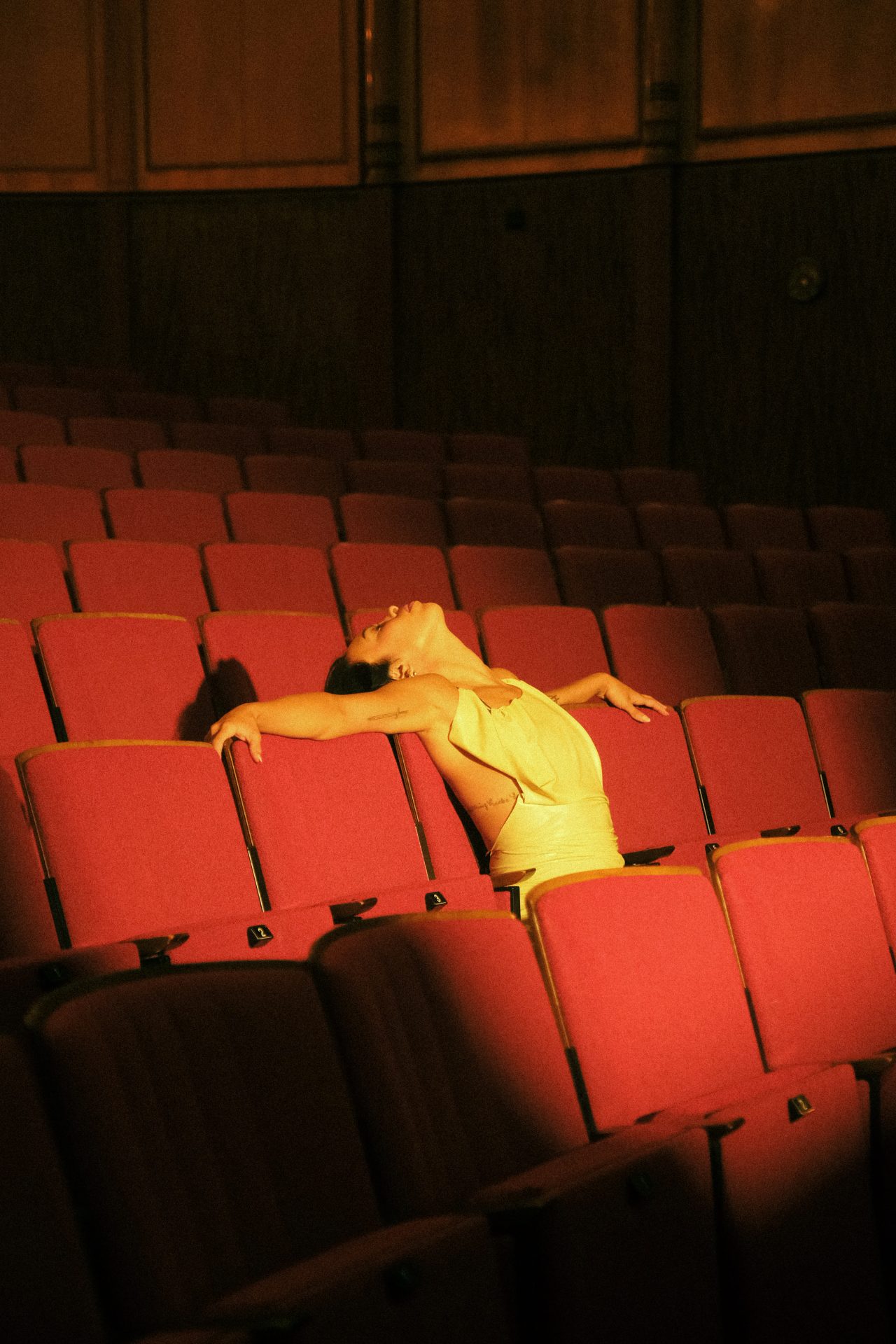

And ultimately, the more people get impacted by a piece, the bigger the conversation it might have sparked, becomes. But while there might be standing ovations in front of the curtain, the picture often looks very different behind the scenes.

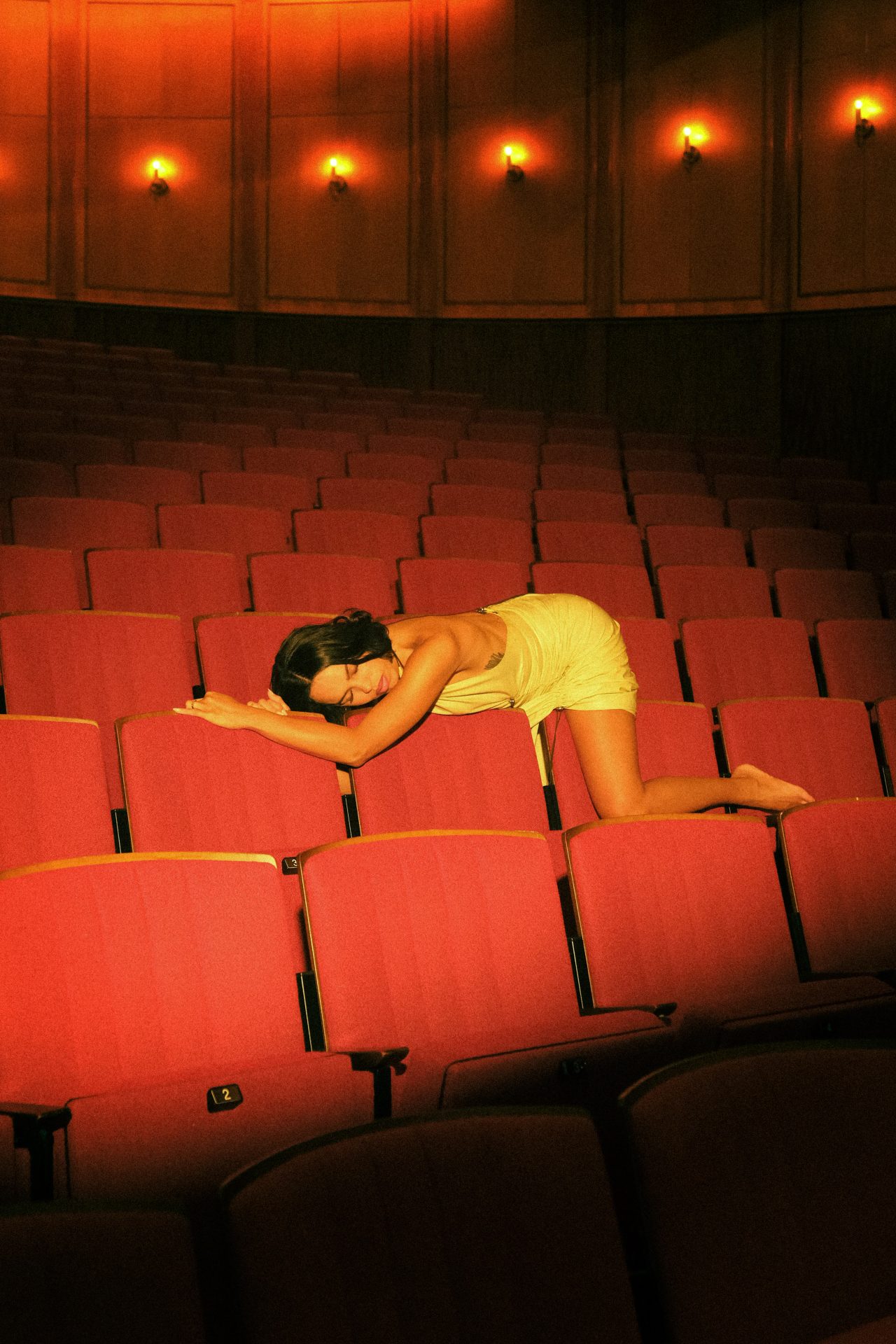

Dancers, actors and other artists are willing to commit themselves to a rollercoaster of emotions. They take a seat and buckle up, filled with hope to become part of a positive and meaningful experience, especially if there is reason to believe, that this ride specifically will be a “safe” one. But if this promise isn’t kept, the ride ends up with nausea again and nothing changes.

“Whenever the art presented to an audience includes multiple diverse perspectives, the audience itself multiplies, becomes more diverse and therefore – larger.”

Sophie Yukiko

Success in front – panic behind the curtain

One could almost get the impression that now, that we finally found the fragile beginnings of a culture that allows us to address misconduct of all sorts and people who have experienced discrimination no longer need to suffer in silence, the list of conflicts to solve gets longer instead of shorter. As if the issues become more instead of fewer. In reality, it only means that people simply have learned to speak up.

But if it isn’t enough to focus on giving space to people who for the longest time were excluded from a serious participation of the high arts and cultural world – what is?

If this exactly were the calls of the last years, why didn’t everything change for the better when they were answered and listened to, not even in those places that cracked open long closed doors just enough to let change glimpse through?

Those who are now finally occupying positions that once seemed unattainable to certain identities and biographies are usually burdened with so many expectations from all sides that they begin working in an unspoken imbalance from day one. “You are the savior.” “You are the change.” “Thanks to you, things will finally get better.” Pressure builds up, and imbalances sooner or later lead to things falling off the shelves, no matter how dusty they are or how long they have been stored there. The truth is, that no single individual can be a messiah of change.

We need something that connects to previous efforts

A practice that goes beyond one’s own identity, challenges the patriarchal order, and – if you will – offers a chance to risk a profound feminist change. A subversive breaking of existing power structures is, according to Judith Butler, who has strongly defined the concept of queer feminist theory, ultimately part of the practice needed to subvert existing norms. And those who are aware of how massive the monster of patriarchal norms is, understand that it can only be brought to its knees through subversion.

So, if we have agreed that (Eurocentric, capitalist,) patriarchal structures are the ones that hurt us and make our coexistence and collaboration so difficult, it will not be enough to simply repopulate these structures with different people by changing the identities of key figures in that system. Maybe we need to ask how we want to interact with each other, rather than focusing on who should interact with whom. It is a big challenge to figure out what systems beyond the ones we know and live by could look like. Especially because we often imagine a practice as a kind of manual that tells us how to do it right and what to use to fill the gaps that emerge when we try to remove oppressive elements. We tend to imagine a new law, a new police force, a new universal rule or instance that decides. But it is precisely about reconsidering (such) principles. And doing so together. For less panic behind the curtain.

Design/ dress: Máthé

“Maybe we need to ask how we want to interact with each other, rather than focusing on who should interact with whom.”

Sophie Yukiko