When most people hear the name Alberto Giacometti they will automatically think of long, slender bronze figures like those he produced after World War II. The fact that the artist was previously part of the Surrealist movement in Paris is unknown to many.

When André Breton, the founder of Surrealism, saw the wooden sculpture “Suspended Ball” by Alberto Giacometti in an exhibition organized by gallery-owner Pierre Loeb in 1930 he was immediately so fascinated that he purchased the work of the still unknown artist. A few days later he visited Giacometti in his studio to ask him to join his circle of artists and writers. Giacometti agreed out of curiosity and against all the warnings he received – and for four and a half years he was part of the Surrealist movement.

Warnings about André Breton

After going to Paris in 1922 Giacometti had worked somewhat hidden away for some years on his sculptures. His acquaintance with Max Ernst, Joan Miró and other important artists at the time from 1928 onwards thus brought about something of a turning point in his creativity. It was through them that he came into contact with Surrealism for the first time – albeit frequently accompanied by warnings against André Breton and his strict influence over the group he had set up.

Alberto Giacometti, Suspended Ball, 1930, Image via art-magazin.de

In 1924 Breton compiled the “Manifesto of Surrealism” and thus struck a nerve in a generation of artists still reeling from the impact of World War I. Ever more writers and fine artists, among them Louis Aragon, Paul Éluard and Benjamin Péret, joined his circle and worked together on the realization of their little revolution: The aim was to reawaken “people’s awareness of their original amazement,” not only on a literary and artistic level, but directly in all areas of life. In order to achieve this immediacy of perception, they set about examining their subconscious and their dreams, which they attempted to give expression to in the form of paintings, sculptures and texts once in a waking state.

The rejection of the bourgeoisie

What they were lacking was a strategy to drive the revolution; all they really had in common was the rejection of the bourgeoisie, morality and religion, and a fascination for the chasms of the human soul. The preoccupation with violence, savagery, sexuality and fears – which were brought to bear in the movement’s own publication “Le Surréalisme au service de la revolution,” amongst other things – offered sufficient inspiration for realization in the form of artistic work.

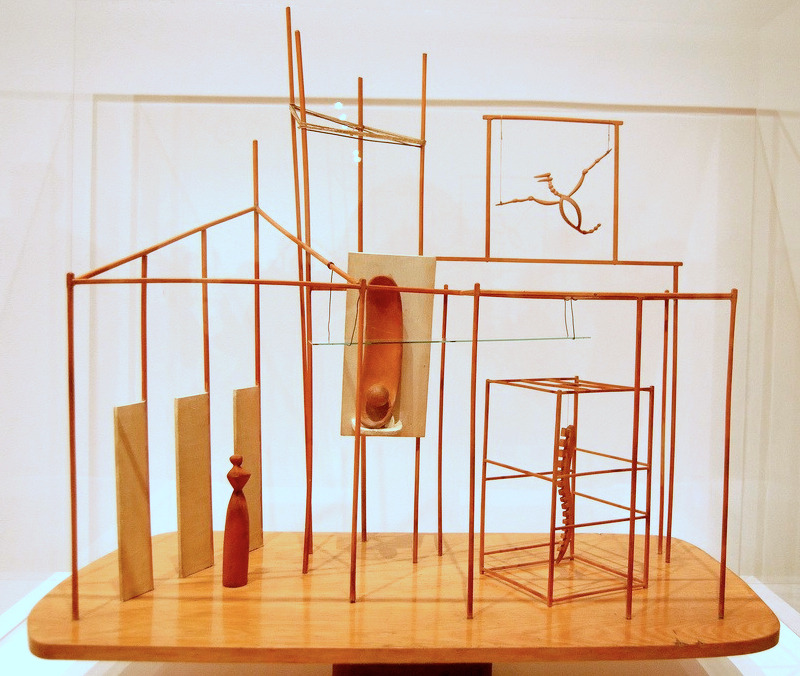

Alberto Giacometti, The Palace at 4 a.m., 1932, Image via onesurrealistaday.com

Giacometti too felt himself drawn to the dark side of the human being. He was fascinated by the chasms of the subconscious that were brought to light in all their true colors in Surrealism. Finally he was able to let his most profound depths come to the surface! Hence the sculptures in particular that Giacometti created in the years 1930-35 – thus during his Surrealist phase – reflect the psychological state of the artist more clearly than ever. They appear dreamlike and hallucinatory, puzzling and metaphorical and even unsparingly brutal. His sculptures from this period often developed “independently” of him, Giacometti said later. He claimed to have already seen them in their entirety before his inner eyes and simply had to make them a reality. This description fitted perfectly with the concerns of Surrealism – although the fact that Giacometti nevertheless left more than sufficient time for the development of his sculptures contradicts the whole scenario again.

Focus on the cage

Around 1931 Giacometti was already a fully integrated member of the Surrealists, attending the gatherings, writing poems for the publication and organizing exhibitions. Yet he also created two of his most important sculptures during this phase, namely “Point to the Eye” and “The Cage.” During the previous two years Giacometti had already addressed love and the dark side of romantic relationships, and now he supplemented this theme with the element of the cage and the latent sexual violence and suppression that go with it. With the sculptures “Point to the Eye” and “Woman With her Throat Cut” (1932), the artist developed the nightmarish visions that trigger anxiety and an underlying feeling of aggression in the observer too. In his composition “The Palace at 4 a.m.” (1932), a puzzling work, Giacometti elaborates on an intense romantic relationship – and here too a cage lies at the core. The artist was certainly never lacking in ideas or inspiration.

Alberto Giacometti, Woman With her Throat Cut, 1932, Image via kultur-online.net

Yet in 1934 Giacometti found himself confronted with a creative problem. Whilst working on “Hands Holding the Void,” a 1.5-meter-high attempt to depict a complete human being, he found it hard to find direction – and therefore began once again to sculpt along more natural lines, even employing a woman to model for him at his studio. He had already used real people as a basis for modeling the two “Striding Woman” figures a year previously; out of affection for Giacometti, Breton had generously overlooked this at the time even though it completely contradicted his notion of art production. Yet now Giacometti was met with rejection among the Surrealists: Everybody knows what a head looks like, Breton railed. When Giacometti then took on another large commission in 1934 which, in the opinion of his artist friends, allied him definitively with the bourgeoisie, he was excluded from the group.

Thus, from that point on, Giacometti lost almost his entire circle of friends at one stroke – yet he was nevertheless all the richer for the wealth of experiences that would flow into his work during the course of his subsequent three decades of further creativity.