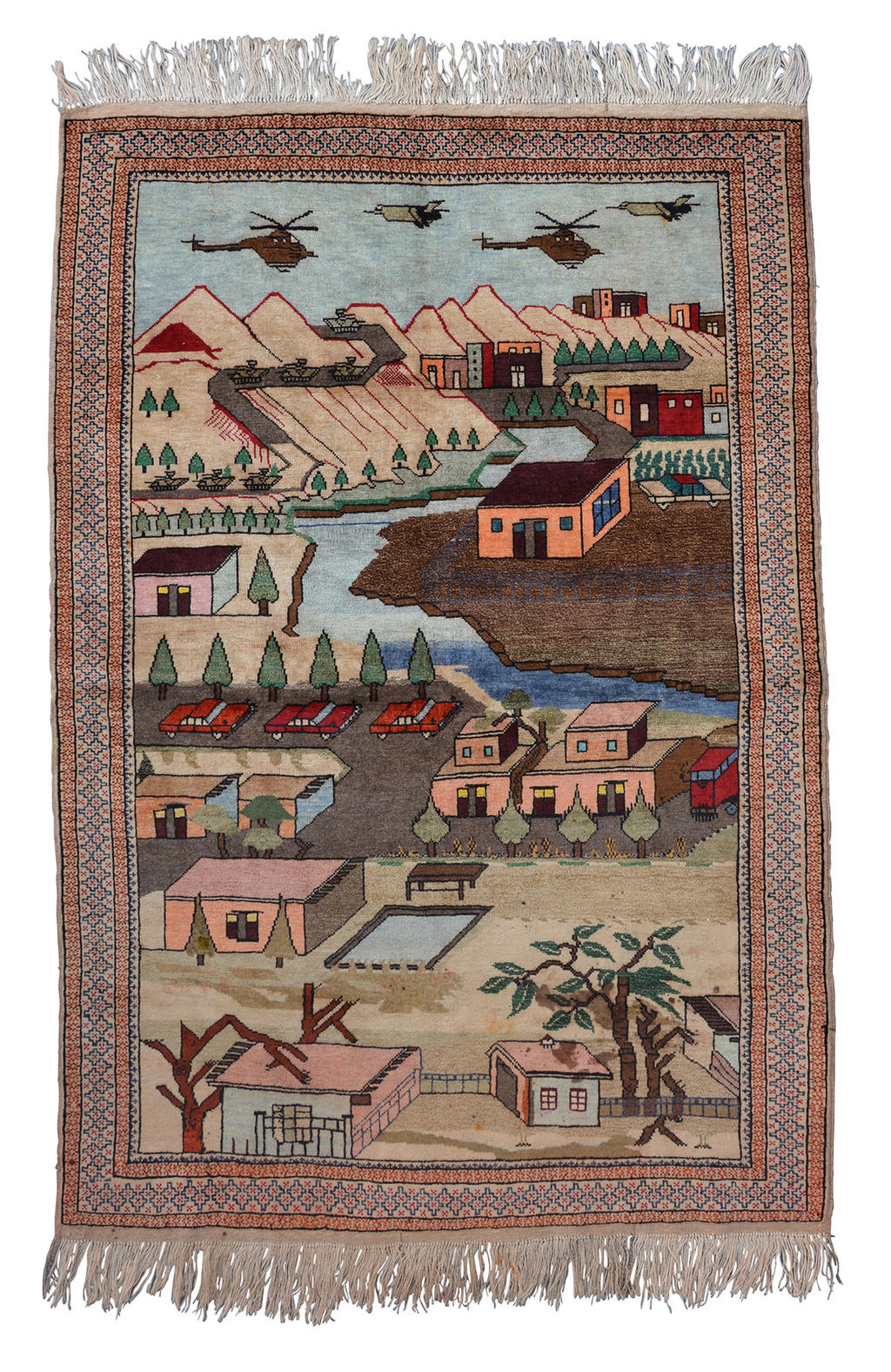

From a distance, the Baghlan rugs look like many other carpets produced by nomads in Afghanistan and the regions adjoining Pakistan or Turkmenistan: Alternating abstract patterns with some figuration, often featuring objects from everyday life, are produced symmetrically or as standalone pictorial themes, woven using boldly colored woolen yarn, some finer, others more coarse.

Only on closer inspection do the geometric forms reveal themselves to be tanks and planes, while the rich green maps are battle zones on which bombs, hand grenades and explosions rain down. “Afghan war rugs”, as the carpets have become known represent something of a curiosity in recent history – and the term is somewhat imprecise given the rich diversity of the genre. These carpets first cropped up around 1979: Shortly after the invasion by Soviet troops, AK-47s started to appear in the midst of folklore themes on the tapestries.

Drones could soon appear on the Afghan carpets

Many of these were designed by the ethnic groups in Afghanistan, but also the Baluchi and Turkmen tribes living around the Pakistani border, which is why the carpets also became known as “Baluchi rugs”. Since then, an ever more extensive pictorial vocabulary has developed, with new tools of war constantly being incorporated – it wouldn’t be surprising, commented American carpet collector and New York Times reporter Kevin Sudeith, for example, if we soon saw drones on the Afghan carpets.

Afghan War Rug, Image via lodownmagazine.com

These woven pieces quite innocently transpose the war zone directly into the living room – not like a work of art, which relies by definition on the opportunities its distance from the world offers, but rather, as a standard component of a home’s furnishings with a folk-like character. It is hardly surprising that the so-called Afghan war rugs soon made a name for themselves as a somewhat macabre curiosity in the Western world. They were traded privately – initially with particular intensity in Germany and Italy, incidentally – and later by specialist traders or illicitly on flea markets, where they suddenly emerged in New York in the mid-1990s.

Interpretations sprouted quickly: Unsurprisingly, the carpets that made patterns of Soviet and American weapons were quickly declared to be symbols of protest against the relevant war. After all, the subversive potential of tapestry work has been recognized. Yet in this case it’s not quite as straightforward, as is also evident in the catalog accompanying the exhibition “Confini e Conflitti. Pictorial Oriental Carpets. Visions of Power” held in Rovereto, Italy in 2015. There Franco Farinelli, a professor of geography, explains that the notion of an inherently pacifist message within the carpets is a sociological-journalistic construct and “one of the least widespread points of view in Afghanistan, even among those who are tired of war”.

Afghan War Rug, Photo by Kevin Sudeith courtesy of Warrug.com, Image via warrug.com

The desire to ascribe such an unambiguous message to these carpets arises in turn from a (geographically) Western and indeed short-sighted perspective on things. It also makes these questionable objects much more palatable. Struggle and conflict reigned in Afghanistan and its neighboring regions long before the first Soviet troops and later American soldiers marched in. So why did little of this make it into tapestry work previously? Might it also have something to do with an experience of unfamiliarity, the novelty of the arriving soldiers and their equipment, which appeared to be so overpowering?

In fascination there is the possibility of disgust as well as attraction

Fascination is, to a certain extent, a precursor to evaluation: Within it lies the possibility both for revulsion and for temptation. Of course, it is very conceivable that the individual carpet-weavers were stanchly against the invasion by the Soviets and that of the Americans later on, experiencing personal suffering, expulsion from their ancestral lands, the loss of members of their families. Yet the incorporation of these sorts of themes, which many nomadic mountain peoples most likely first saw on the illustrated information flyers that were dropped on their territories, is nevertheless still far from a given.

Afghan War Rug, Photo by Kevin Sudeith courtesy of Warrug.com, Image via warrug.com

Afghan War Rug, Photo by Kevin Sudeith courtesy of Warrug.com, Image via warrug.com

Reducing these works solely to a symbol of protest also ignores the longstanding tradition whereby the rugs were woven by originally nomadic carpet-weavers. Creating a carpet is about more than just finding a theme – it requires time, material and contexts in which its development takes place. Before the Taliban took control, for example, Afghanistan was an emerging nation in which women (albeit not all of them, as popular pictures from that time might imply) would walk the streets in short skirts, and people could go to the cinema in the evening to watch a film.

It is impossible to tell where exactly the phenomenon originated

In the meantime, entire expert websites have emerged that deal exclusively with these kinds of “war rugs”, categorizing them into various schools and styles. Yet precisely where the phenomenon originated is not known. Perhaps it was initially only very isolated examples that happened to incorporate the novelty of AK-47s in their patterns and images. It is quite likely that the first artisans to create these kinds of carpets had actually only seen their motifs in pictures.

Afghan War Rug, Image via lodownmagazine.com

After 9/11, however, a new kind of carpet motif developed, illustrating the attack on the World Trade Center with a sometimes-drastic infatuation with detail. These images were again ones the carpet-weavers had seen only on the television, or more likely in flyers and photographs in which the terror attack was linked by way of argumentation to the military action in Afghanistan. We cannot say for sure whether the depiction of 9/11 is celebrated in a cynical manner, condemned admonishingly – or whether, as in the war carpets dating back further, it was initially simply a representation in the actual sense, with no formulated intention.

For the later carpets at least, there are now also very different, more contemptuous explanations: The hype surrounding the war carpets has of course spread, and the rising demand has led to a significant increase in their production. Often enough, the tapestries sold under this label are, for their part, reproductions of existing carpets and are not infrequently produced by children.

Afghan War Rug, Image via lodownmagazine.com

The authentic expression that the well-paying collector wants for his money is, in many cases, nothing more than a marketing argument. Hence, the Afghan war rugs have ended up like any successful product and are now no longer merely an object of fascination for collectors, but have long since become a popular souvenir, especially among members of the military who have brought such carpets back for their families (many Afghan traders get special permits to sell them directly at the military bases). This might seem cynical and macabre, rather like the motifs themselves, yet it is testament to the deep-rooted human desire to take something home from the places we have seen.

The rugs have long since become a popular souvenir among members of the military

Where images, with their digital omnipresence, are now perceived as virtually non-existent, as a manually produced medium a carpet offers extraordinary added value. Its production takes time. And when suddenly, amid the centuries of tradition and craftsmanship, war and conflict appear in their latest guise, then clearly something very remarkable happens. The less we try to cast aside their ambiguous character, the less they are reduced to this admittedly compelling symbolism, the more these rugs confound us.

Afghan War Rug, Photo by Kevin Sudeith courtesy of Warrug.com, Image via www.warrug.com

Afghan War Rug, Photo by Kevin Sudeith courtesy of Warrug.com, Image via www.warrug.com