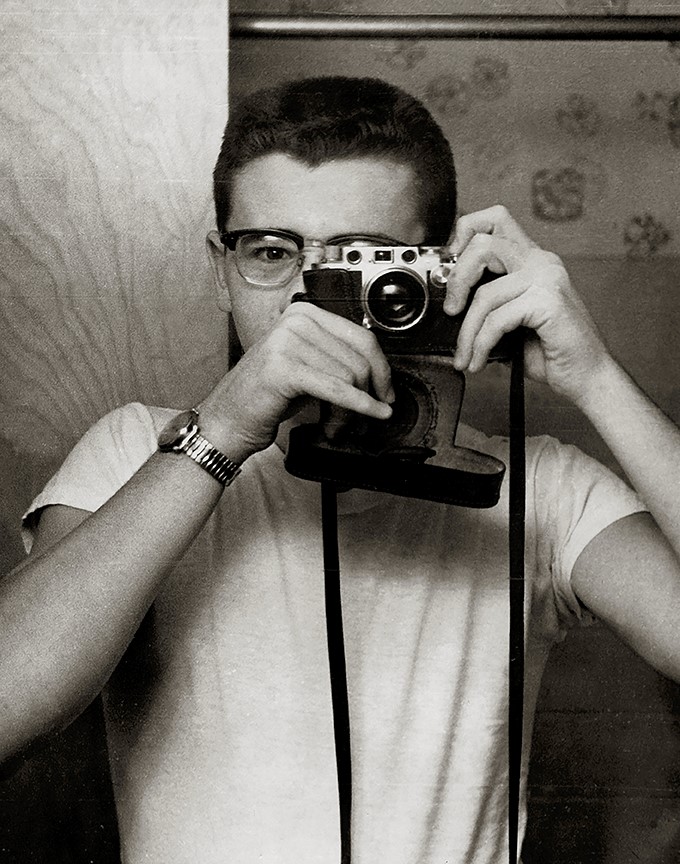

In the course of his career, photographer Abe Frajndlich has portrayed innumerable people, including not least, as you can see here, himself.

Frajndlich has lived for five decades in New York. That said, he has a special relationship to Frankfurt: He was born in 1946 the son of a Polish Jewish couple as Abraham Samuel Frajndlich in a Displaced Persons camp in Zeilsheim just outside town. His was a conscious decision not to allow the past to define him, he says. Later, after he had long since put down roots in America, Abe Frajndlich regularly produced photos for the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung’s supplement.

At one time, like various of his American colleagues in the creative world (Philipp Guston, Frank Gehry), he thought he should abandon his Yiddish surname as it might get in the way of his professional life, but by then his career had already taken off. “It evidently didn’t harm me,” Frajndlich quips with his typical dry humor. We first sat down and talked last year, when he opened a major retrospective of his work at Fotografie Forum Frankfurt. Back then, we already found ourselves talking about the ambiguous joy of being able to look back on your own oeuvre. On the one hand, it’s a welcome occasion to see what you have achieved, on the other your work is never complete. Now we’re sitting down to talk again, this time by Zoom.

Do you remember the first artwork that really bowled you over – perhaps one that gave rise to your wish to become an artist yourself?

Abe: There’s a story I tell in my book “Seventy Five at Seventy Five”. I was at college at the time, just close by the Chicago Art Institute, busy studying literature. It was probably during my last term, so in the summer of 1968. I had finished most of my classes and had one more seminar to go. The lecturer gave us the following task: “Go to the Art Institute and choose a piece of art that appeals to you.” So, there I was walking around, and it’s a great museum with works of art from all the different centuries, and I came across Rodin’s “Adam”. It’s a pretty large sculpture; it must be over three meters high. There’s that famous passage which goes “…and God took mud and made man,” or something like that …

In Genesis 2.7, where God forms Man from dust or earth as it were …

Abe: Now Rodin took that idea and cast an image of it in bronze, which of course itself is part of the earth, meaning it was once mud, and thus created Adam. When I looked at Adam’s feet it became abundantly clear to me that here’s an artist who has taken something completely lifeless and breathed life into it – in a manner like a god. In that very moment I had the thought: Whatever it is that man is doing, in some strange way I want to be part of it. I did not yet know what exact shape that wish would take. But I wrote an essay about what the sculpture triggered in me. That was in 1969. In 2012, one of the teaching assistants back then wrote me a letter saying she had never forgotten that essay and whenever she saw on the Internet that I was now actually hard at work as an artist she found herself thinking about what I had written. It made me realize once again that back then in the Art Institute I had had my “Genesis Moment”. When I was later taking photos, the work repeatedly connected me back to that experience. A deep desire, not at an intellectual but at a physical level. So that was the first artwork that really spoke to me.

Have you been back to look at it since? Has it changed for you since then?

Abe: Oh yes, and remember there are several different versions of Rodin’s “Adam”. I’ve seen the sculpture in Paris, and there’s another one here, in Cleveland, too. However, the strange thing with those initial moments, and it’s a bit like making love the first time, is that: It’s somehow never exactly the same. Because you discover an entire new world. All your senses are heightened. Once you know it you can never again look at it through the same eyes. When I create images, I try repeatedly to enjoy that moment anew. I do it out of the need to stay wakeful. To stay in my young mind. To look at the world through the eyes of a three-year-old.

During our last conversation we at some point came up with the motto: Photography is always now …

Abe: Yes, absolutely. Photography is always now. Because the need and the moment that give rise to the photo will never again be repeated. The light, the circumstances. They’re all only there once. And that in my opinion is what constitutes the beauty of photography: It forces you to be in the here-and-now. I’m constantly being asked what my favorite image is, and I always give the same answer: The photo that I’m going to take tomorrow. And today, now that I’m a truly old man, well compared to a 32-year-old at any rate, that’s becoming all the more important. To live in the here-and-now, and not in the past. I’m still incredibly enthusiastic about the medium I work in.

Is there a continuity in this repeatedly New, something that you have always handled in a particular way, from your first image right through to today?

Abe: I think that what keeps photographers going, and this doesn’t just apply to me, is their great level of curiosity. We go through the world like that small child who is forever asking: Why, why, why? And the camera’s the perfect instrument with which to ask these questions. Not that it always gives you answers. But it is a perfect way of going on asking. What is it that we are looking for? How can you say something within the confines of this small theater you are watching – and say it such that it also speaks to others? That’s the challenge.

If you can see, you can see. It’s that simple. Art is something that you can’t learn. You can learn specific techniques, but the real act, creative seeing, either you have it, or you don’t. I never attended an art academy, I never studied photography. Slowly, only of late, have I started to feel that I have the eye to see things.

Was there the one moment when you were looking at one of your own works and thought: “That’s really good, now, that’s art.”?

Abe: It takes a lot of time. In the beginning when you photograph you only make pictures. Later, looking back, compiling them, when you do that for 15 or 20 years, then you at some point perhaps see that some of what you have made was already heading in the direction of art back then. But the thing about of all this is that if you say it about your own stuff then it simply sounds like so much BS. You can’t simply say “That’s art” or “I’m producing art”. That would be pretending. And I don’t want to act as if because I hold what I do in far too high regard for that. Others have to judge it – often that only happens over time, too. I know that Rodin makes art. I don’t know whether Frajndlich makes art. Frajndlich makes photos.

Over the course of more than 50 years you have photographed countless people, including people on the street. Over that period, photography has undergone massive upheaval. Do you notice those changes in your daily work?

Abe: Yes, an awful lot has changed, if only owing to the fact that today everyone has one of these [point to his Smartphone], and they are really highly developed instruments. The entry level back then was completely different. So, if you wanted to create a photo you could at some point have 35mm film developed at a drugstore or maybe use one of the Instant cameras. Or go to a darkroom. That was of course a completely different world. When I back then produced photographs for the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, for example, I was told: If someone opens the color supplement, they’ll look at the images for maybe a quarter of a second. You need to produce photos that they’ll pore over for at least a second. Today, if people look at images on Instagram or wherever else, their attention span will be max one tenth of a second. Billions of images are made every day of the week, the world over. Instead of writing letters, people stand in front of a camera and then share the image in that very moment. You can no longer compare the level and speed of the pictures taken with what they used to be. As a result, the attention paid to each individual image drops – sending images itself become a form of communications, but you do not know whether the sender of the image is not also sharing it with five other people at the same time.

Let’s turn now to projects and plans: You’re working at the moment on your book “Women in the arts”.

Abe: I certainly am! And it really includes everything, from a picture I shot right at the beginning, Jane Fonda, 1970, that was even before I worked with Minor White, via Louise Bourgeois, Yoko Ono, Eileen Ford, Cindy Sherman, Leni Riefenstahl, Barbara Sukowa, Isabel Allende, Leonora Carrington… it’s a total of 100 portraits, and there’ll be a separate text on each of them.

My favorite image is the one I’m going to take tomorrow

Your image of Leni Riefenstahl, who came to fame with Nazi propaganda films and later pursued a strong career in the art business as a photographer without anyone really objecting, really stands out: She really looks almost like a ghost. How did the image come about?

Abe: That was at the Frankfurt Book Fair in 2000. Taschen Verlag had just published “Leni Riefenstahl: Five Lives” and part of the ad campaign was a huge portrait of the young, 27-year-old Leni Riefenstahl. It was a good three meters high. I stood there alongside several other photographers, the film in my camera was a Kodak Plus-X that ran at ASA 125, meaning it was quite slow, and I was forced to take the shot at a quarter or an eighth of a second. The result was that “specter-like” impression of Leni, who was 98 by then. She was of course associated with the days of Adolf Hitler and produced Nazi propaganda. But my interest lay in the fact that she had created remarkable photographs across numerous decades and genres and was an important 20th-century imagemaker. And because she just happened to be in front of my camera at that particular moment.

Why “women in art” in the first place? And why now in particular?

Abe: Well, “Everyone in Art” would have been spreading it a bit too thin … I photographed so many women who had a considerable impact on the cultural world in which we live today. I simply thought that the time has come, as the lion’s share of art history still ignores women. It’s not just women photographers, but women designers, women filmmakers, writers, athletes …

…and women curators.

Abe: Correct. I recently photographed Barbara Tannenbaum, Chief Curator of Photography at the Cleveland Museum of Art, in front of one version of the famous Picasso painting of Gertrude Stein. I had to convince her first, though that given Barbara’s importance for the photographical community today meant Gertrude was an appropriate author in front of whom she could be portraited. At any rate, at the time when Gertrude saw the portrait of her, she said: “That’s not me.” And Picasso said: “But it will become you.” He had that vision. In my opinion, that’s also what photography is about.