5 questions for Salma Lahlou from ThinkArt Casablanca

09/05/2024

10 min reading time

Salma Lahlou is an independent curator. Her exhibitions and research projects continuously engage with the Casablanca Art School. We spoke with her about her first encounter with the school and the great legacy and potential that its teaching holds for Morocco today.

1.

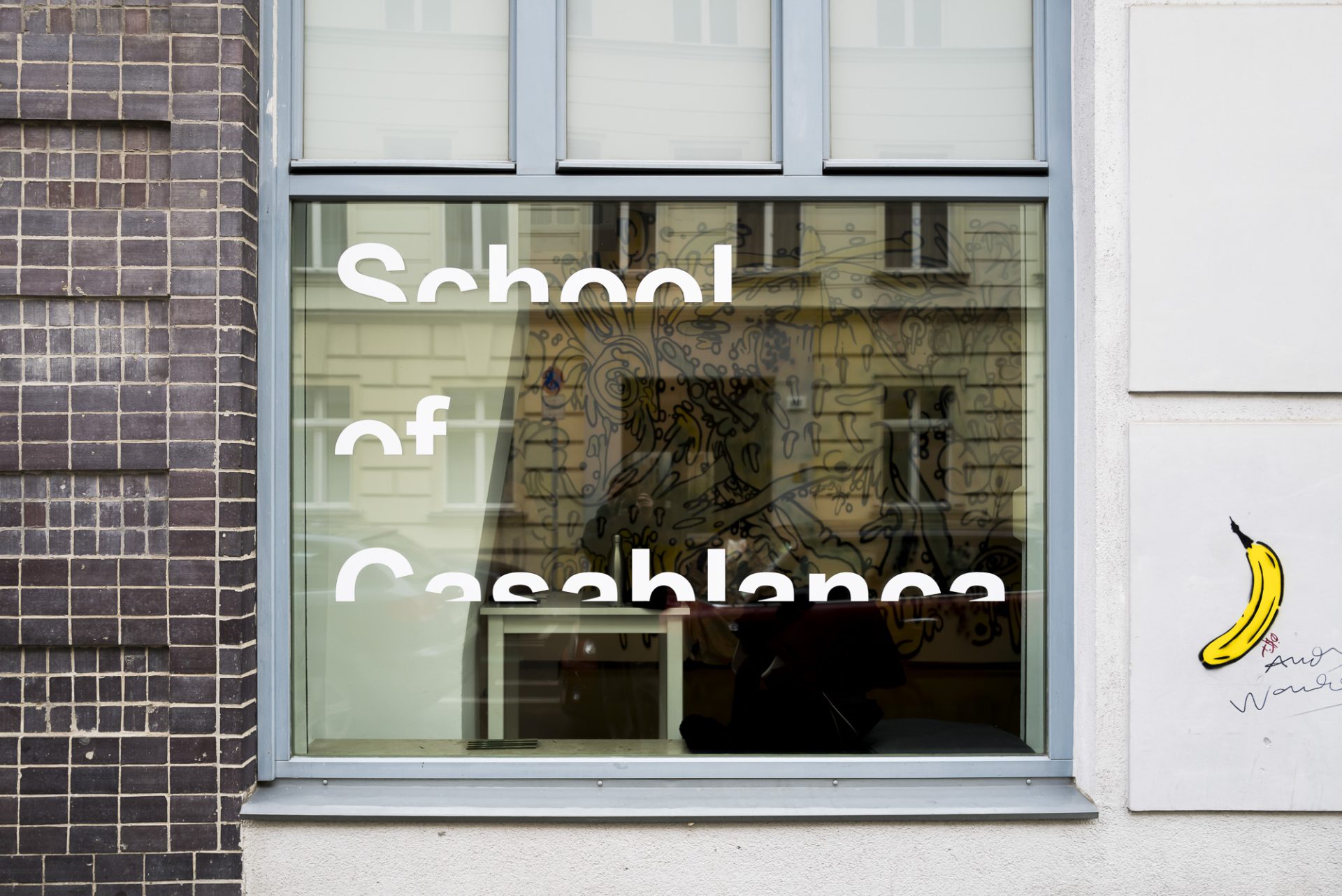

Salma Lahlou, you are an independent curator and director of ThinkArt Casablanca. Until mid-January of this year, you showed the exhibition “School of Casablanca” at the ifa Gallery Berlin, which was realized by you and ThinkArt together with the KW Institute for Contemporary Art (Berlin) in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation, the ifa Gallery Berlin, the Goethe Institute Morocco and Zamân Books & Curating. What was your first encounter with the Casablanca Art School and what inspired you to undertake this large-scale research and exhibition project?

Salma Lahlou

My encounter with the Casablanca Art School dates back to 2015. For the 6th edition of the Marrakech Biennial, entitled “Not New Now?” (February-June 2016), Fatima-Zahra Lakrissa and I were invited by Reem Fadda to curate an exhibition about the school and the people who shaped its new pedagogy.

Established in the 1920s by the French colonial authorities and officially inaugurated in 1951, l’École municipale des beaux-arts de Casablanca (the city’s fine art school) played a key role in breaking new ground and reshaping the epistemology of cultural disciplines, carried forward by an entire generation of artists, poets, writers, filmmakers, architects, playwrights, and musicians. In the 1960s, the school underwent a phase of renewal spurred by artists like Farid Belkahia (1934–2014), Mohammed Chabâa (1935–2013), and Mohamed Melehi (1936–2020), the art historian and anthropologist Toni Maraini, as well as Bert Flint (1931–2022), an Afro-Berber art researcher and linguist, and a passionate expert on folk art and rural traditions. They were later joined by three other artists and facilitators, Mohamed Ataallah (1939-2014), Mustapha Hafid, and Mohamed Hamidi, who brought together artistic-aesthetic notions with ideas of social reform and emancipation to form a joint cultural project. What was then referred to as the Casablanca Art School designates both the institution during its golden age (1964–1969) and the aesthetic revolution embodied in the works of the artists-tutors.

Conducting, processing and exhibiting this research became much more than a simple object of study. It made me aware of a major problem: the failure to pass on whole swathes of our identity. As little is passed on to us, we have to appropriate the knowledge, gestures and narratives that constitute our collective memory. I remember being quite upset when I read Abdellatif Laâbi’s “Le gâchis”, published in 1967 in the avant-garde cultural publication “Souffles” in its special issue on the plastic arts in Morocco. I couldn’t understand why this periodical wasn’t studied at school. Can you imagine that at the École Supérieure des beaux-arts of Casablanca, this founding period of our social, cultural and political identity is not passed on to the students?

And it is precisely in response to this “failure to transmit” that we undertook the “School of Casablanca” project.

2.

The participants invited to the exhibition ranged from artists, designers and curators to independent academics. All of them have conducted research and field studies during a residency program in Casablanca. Were there any findings that stood out for you, and could you tell us a little bit about them and the residency program in general?

Salma Lahlou

The Residency and public programs took place between September 2020 and December 2022. Each participant took a critical look at one of the issues raised within the school that echoed their own practice, with the aim of posing questions about the legacy of the Casablanca Art School within the current socio-political climate of Casablanca and Morocco.

I will outline the parts that constitute the school’s contribution before moving on to the participants’ research proposals: The artists and theoreticians of the school positioned themselves by advocating the visceral link between modern artistic production and plastic traditions; an aesthetic of ornamental abstraction; flattening the hierarchy set up by the French between fine and traditional arts; the abolition of the divide between art and life; a transversal approach to art; the status of art as a space for shared knowledge and experience; the role of the artist as the producer of a social and cultural project; making art public by weaving their art into the fabric of the city and greater society.

I loved so many proposals if not to say all of them. I was particularly taken with Manuel Raeder’s manhole covers and street furniture, their play on the public’s uses and projections, where nothing is static. The fiction-reality that Fatima-Zahra Lakrissa imagined around the epistemological rupture between Bert Flint and Toni Maraini helped to fill a void around questions of validity and hierarchies between academicism and heuristics. Céline Condorelli inscribed the visual language of abstraction as women’s labour in a monumental installation she produced using carpets collected in Boujaad as the source of her production, at the same time as setting up a support structure for weavers in collaboration with the erudite carpet dealer and collector Rabii Bibi Alouani. Abdeslam Ziou Ziou teamed up with artists to create a space for the display, reception and discussion around the issue of art and psychiatry, engaging with his father’s work, a psychiatrist who worked with the artists of the Casablanca Art School at the Berrechid psychiatric institution in 1981. Amina Belghiti looked at the sonic imaginary of the period, listening to the gaps, absences, silences in and around the school. Peter Spillmann made available Marion von Osten’s archives on Casablanca in a modular container with a significant piece called “la bibilothèque de passage” at ThinkArt. To name but a few.

3.

The video series “School of Walking” by the artist duo Bik van der Pol was created as part of that residency program and shows city tours with various local cultural workers who present Casablanca as a modern city and creative center where artists of the 1960s and 1970s developed their dreams of a common future. Part of the video series is currently on view in the SCHIRN Rotunda, which is open to the public. What fascinated you about the video series?

Salma Lahlou

Liesbeth Bik and Jos van der Pol were among the first residents. For them, walking in the city is a natural ‘modus operandi’, as they practice it systematically, as a lifestyle. I immersed myself in their practice by studying their body of work, and it was through them that I was truly able to assimilate what art as a social practice implies. And thankfully so, because I could better understand Ruangrupa’s Documenta!

In the course of our many discussions, Liesbeth invited me to activate another prism and see objects as models of potentiality or ‘tools for potential’ by integrating the nuance between what objects do versus how objects look.

Walking has the ability to connect us differently to each other, widen our perspectives and make us aware of the urban terrain that was activated by artists from the outset. It was particularly meaningful to me to invite Hassan Darsi, whom I see as one of the most significant socially engaged artist working in Morocco. His work on the Parc de l’Hermitage was a milestone for my generation because it disrupted administrative apathy and enabled local residents to reclaim a public park that had been left in a state of complete disarray. Fatima Mazmouz embodied our political resistance in an active march to revisit streets named after lesser known historical figures whose stories are not often told to younger generations. Mohamed Fariji and his project for a collective museum in Casablanca showed how the city neglects its architectural assets, letting them rot away while we suffer from a lack of available space for talks, exhibitions and so on.

Walking activates a different kind of attention because it involves the body, engaging the senses as well as the mind. It bypasses the lecture format, which puts the lecturer at the centre; instead, informal conversations abound. It’s a way of experiencing the city in a different way to the traditional guided city tours. Casablanca is not a single trail. Numerous routes and sections exist, allowing us to forge new bonds and provoke unexpected discussions between walkers, which opens up new perspectives. We continued these walks during the exhibition in Casablanca and I hope to keep organizing them in the future.

4.

In your opinion, what is the great legacy of the Casablanca Art School – what traces can still be found today in the city or in Morocco as a whole?

Salma Lahlou

I would say that it’s about taking into consideration the socio-political context of the time and responding to it with actions that are relevant both formally and the space in which they exist. Initiatives such as ‘La Source du lion’, ‘L’Atelier de l’observatoire’, ‘Darjaa’ and more recently ‘Malhoun’, ‘Siniya’ and ‘CARCDAM’ are examples of this awareness.

5.

Finally, let’s take a look into the future: which strategies and methods of the School do you think have the greatest potential for the future in the current socio-political climate in Morocco?

Salma Lahlou

Collaborations, research, field work, experimentation, care and disruptions are key.

You may also like

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consetetur sadipscing elitr, sed diam nonumy eirmod tempor invidunt.