In a film series, Oliver Hardt combines the themes from Kara Walker’s work with the perspectives of Black people in Germany. In conversation with author Eric Otieno Sumba, the filmmaker tells us what to expect on these evenings.

“Black is not a Color” is the film series accompanying the exhibition “A Black Hole is Everything a Star Longs To Be”. In an interview, Frankfurt-based filmmaker Oliver Hardt, who curated the series, tells us what viewers can expect on the four evenings.

Eric Otieno Sumba: The film series presents ten films over four evenings. To what extent does the film program link up to Kara Walker’s work?

Oliver Hardt: The film series takes the themes Kara Walker addresses as an occasion to reflect on what it means to be Black in Germany. It is not about Kara Walker as an individual or as an artist. It’s about Black identities, about exploring the tension that exists between self-image and external image, between attribution and self-determination. The filmmakers’ works attempt to gain back control over their own image by questioning longstanding narratives and replacing them with their own. Within the films, Black identity is understood to be an ongoing process of self-questioning and the negotiation of one’s own position within the dominant white culture. That’s something I see in Kara Walker’s work in the whole radicalism of her pictorial language, somewhere between profound pain and unfathomable comedy.

“There is no question that representation is central to power, the real struggle is over the power to control images” wrote Thelma Golden in the early 1990s. It is a truism today, in a way, but I believe you cannot emphasize enough just how important that is. Film is a visual medium in which you can negotiate visual forms of representation in a discursive way. That plays a crucial role in the series.

It’s about Black identities, about exploring the tension that exists between self-image and external image, between attribution and self-determination.

Nine of the films being screened were made by Black filmmakers since Reunification. Why this period and in which genres do the selected filmmakers operate?

The oldest film is from 1991, the newest from 2021. If you consider the film series as a whole, then you can discern a lot about the sensitivities and changes in Germany since Reunification – or that’s my hope, at least. There hasn’t been a huge amount of films made by Black filmmakers in Germany over the last 30 years. Nevertheless, all formats are represented, albeit with a clear focus on documentaries and to a certain extent also short films. This is down to economic reasons, on the one hand, but Black documentary filmmakers have, on the other, a greater chance of saying something about their own experiences than in feature films, where you often have to go around the houses quite a bit.

The documentary film as a direct expression of personal experience and world view is in the foreground. In recent years, however, a lot has been happening in feature films: There are now more Black and post-migrant perspectives in cinema and television. With “Ivie wie Ivie” by Sarah Blaßkiewitz, we have one of these very new feature films in our program. The film tells the story of two Afro-German half-sisters, who only get to know each other as adults.

How do you explain the audience success in Germany of the only non-German production in the film series, Raoul Peck’s “I am not your Negro” (IANYN)?

First of all, it’s simply a really great film. Added to which, both Raoul Peck and James Baldwin, whose books have all been published in German, have been the subject of much attention here for some time. Another important explanation for the success, however, is that in Germany we like to look to the USA when it comes to issues such as racism, violence, and discrimination. There is a kind of externalization in this that permits the German public to look elsewhere and see how bad things are there in terms of certain ideologies. At the same time, this frees you from the task of looking outside your own front door. A certain forgetfulness surrounding the history of German colonialism and its aftermath, which can still be felt today, no doubt also plays a role here.

The majority of filmmakers nevertheless seem to have been in Germany for only a few years when the films were made and three of them no longer live in Germany. Did the films develop in an educational context?

It’s a miracle that some of these films exist at all. They would never have been made in the first place outside of a university context. Two of the films – “Fake Soldiers” (1999) and “Black in the Western World” (1992) – I only discovered via the “Fiktionsbescheinigung” series at the Berlinale 2021. In the latter case in particular, I was absolutely amazed at how accurately it reflects being Black in Germany. You think there’s insanely little out there, but there is actually far more film material than you realize, and that’s a matter of accessibility of archives and archive directories.

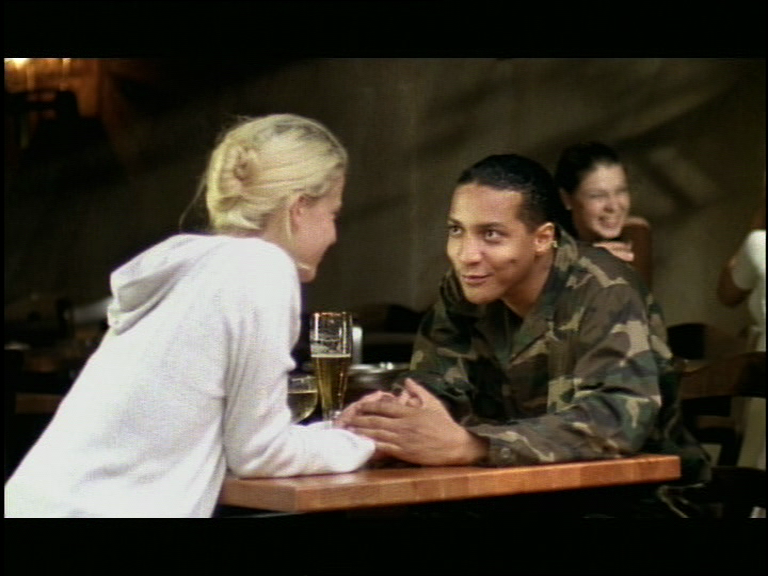

In fact, the films themselves convey the ideas that filmmakers had and have about their perspectives as Black filmmakers in Germany. It’s not always explicitly the theme, but it often resonates. “Fake Soldiers”, for example, starts with the premise that Africans and Afro-Germans have a much harder time than the cool African-Americans. Idrissou Mora-Kpai turns this into a little comedy-like, but actually very serious, short feature in which two Afro-Berlin boys pretend to be GIs to score points with German women. African-American culture has and had a more self-evident presence in Germany than the African culture, or even that of Afro-Germans.

So you learn a lot about the context of Black people’s lives in Germany from the early 1990s until today. It’s a kind of archival achievement that the films accomplish here…

That’s why the variety of genres and the timespan is also so important. There is just one copy of “Black in the Western World” at the Deutsche Kinemathek in Berlin. It made me happy to see the film there and to be able to borrow it for the program, but it also made me think about accessibility. How much great material is still lying around there that we know nothing about? Archives can preserve things, but they can also swallow them up, as filmmaker Karina Griffith once put it.

Three films from three different decades have the English word “Black” in the title, or have English titles even though they are German productions. Why is the German word “Schwarz” not used?

Use of the English word “Black” relates primarily to the difference between the German- and the English-speaking worlds with regard to the discourse surrounding “race”, “identity”, “blackness”, etc. With “Black Deutschland” (2006), my own film, I wanted to mark the difference between what is seen as “German” and what is meant by “Black”. This notion of “Black” as something that doesn’t belong is implied in the title. The main point, though, is that “Black” has for a long time had political connotations, specifically due to the “race” discourse in the English-speaking world. Unfortunately, we’re a little way behind on that in Germany. There are loaded terms like “race”, which are basically not usable in this way and which mean that we often have to borrow terms here first. That can and will end over time, but at the moment it seems to be the only adequate way to talk about it.

Film series with Oliver Hardt

BLACK IS NOT A COLOR

THURSDAYS AT 7:30 P.M., OCT. 21 + 28, NOV. 4 + 11, 2021