Urbanization, road building, livestock farming – wherever humans propagate there is at most room for the urban jungle. Consequently, our fascination for untouched nature is all the greater. But where can we still find it?

1. The Danakil Depression

If “wild” is wherever humans or animals are hardly able to gain a foothold, then the Danakil Depression between Eritrea, Djibouti and Ethiopia is without a doubt one of the wildest places on Earth. Average annual temperatures of 36 degrees Celsius and highs of 65 degrees make this desert region, which covers some 10,000 square meters, uninhabitable for most lifeforms. And the region’s hospitality is not exactly increased by its active volcanoes: The gases escaping from large sulfur holes immerse parts of the Danakil Depression in garish, seemingly extraterrestrial yellow tones and lava vapors rise up out of deep craters. Oryx antelopes and dromedaries are among the few animals that feel at home in such an environment. The only humans for miles are (now armed) Eritrean separatists, who use the inaccessible territory as a refuge, and the Afar nomads. The latter mine salt on the beds of lakes that have long since dried up, subsequently transporting it in large caravans to sell in the Ethiopian highlands.

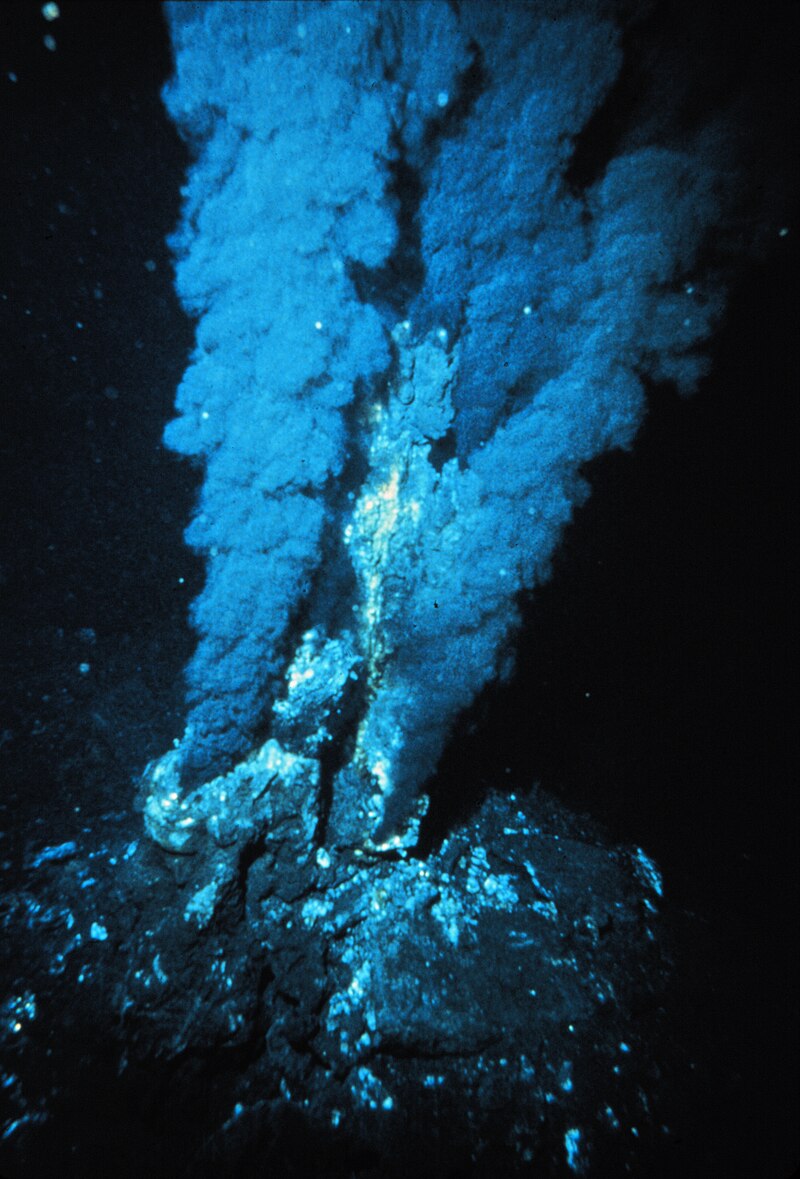

2. New Hebrides Trench

The deep sea is one of the last truly untouched regions of the Earth. And one of the least explored parts of the deep sea is the New Hebrides Trench, which extends over 1,300 kilometers of Pacific Ocean floor northwest of New Zealand. The probably last entirely unknown animal species in the world live here at depths in excess of 7,000 meters. Yet it was mostly gaping emptiness that scientists found on the first and to date only expedition into the trench, conducted in late 2013 using underwater robots. Apart from from cusk-eels, a type of bony fish, and a few cutthroat eels, the camera lens captured no living creatures – perhaps the best evidence that things aren’t necessarily always wild in the world’s wildest places.

Image via wikimedia.org

3. Gangkhar Puensum

There is no doubt little to be found, aside from snow and ice, on the peak of the mountain Gangkhar Puensum in Bhutan, but at least there is heavenly peace. After all, with an elevation of over 7,500 meters it is considered the highest as yet unclimbed mountain on Earth. Between 1986 and 1994 a total of four expeditions failed in their attempt to reach the summit. The government of Bhutan subsequently prohibited all climbing expeditions beyond 6,000 meters – and not only due to safety concerns. Indeed, the fact that the mountain wilderness of Gangkhar Puensum is to remain untouched for the foreseeable future is not least down to a belief held by Bhutanese settlers, who live at the foot of the mountain. For them, the summit has housed powerful protective spirits for centuries. And they must not be disturbed under any circumstances.

4. Vale do Javari

In the west of Brazil, encompassing an area larger than all of Austria, is Vale do Javari, the Javari Valley. It is home not only to the country’s last isolated peoples – indigenous tribes that have no contact with the outside world – but possibly a great many rare plant and animal species as well. Yet nothing more is known: Exploratory flights, satellite photos and the odd government exhibition into Vale do Javari are the only sources of reliable information. Officially, only recognized scientists and, in dire emergencies, doctors may enter the valley. Nonetheless, the untouched wilderness in the far west of the Amazon may soon be a thing of the past. Road building contractors, oil companies and the timber industry have been exerting pressure on politicians for years and want to advance into the Javari Valley. Illegal logging and the activities of gold diggers, who enter the region via the border to Peru, are already a problem today.

5. Sakha Republic

With a population density of 0.3 inhabitants per square kilometer, the Russian Sakha Republic is among the Earth’s most thinly populated regions. The area is almost as large as continental Europe and is home to just 950,000 people. That may have something to do with the fact that temperatures in Sakha regularly drop below minus 40 degrees Celsius. The permafrost soil reaches depths of up to 1,000 meters in some parts of the republic and would need several centuries to melt in slowly rising temperatures. In places inhospitable to humans it is the flora and fauna that benefit in Sakha: Many kinds of species of birch, pine, fir and aspen have thrived here for hundreds of years and rare animals such as the sable and wolverine as well as large packs of wolves can be found here. Moreover, in the north of the republic, on the coast of the Arctic Ocean, endangered bird species such as the Siberian crane and Ross’s gull nest.