Bobbed hair, tail coat and cigarette holder: Women in the Weimar Republic liberated themselves from the rigid corset imposed on them and did not give a damn about conventions. In art, too, the image of women altered.

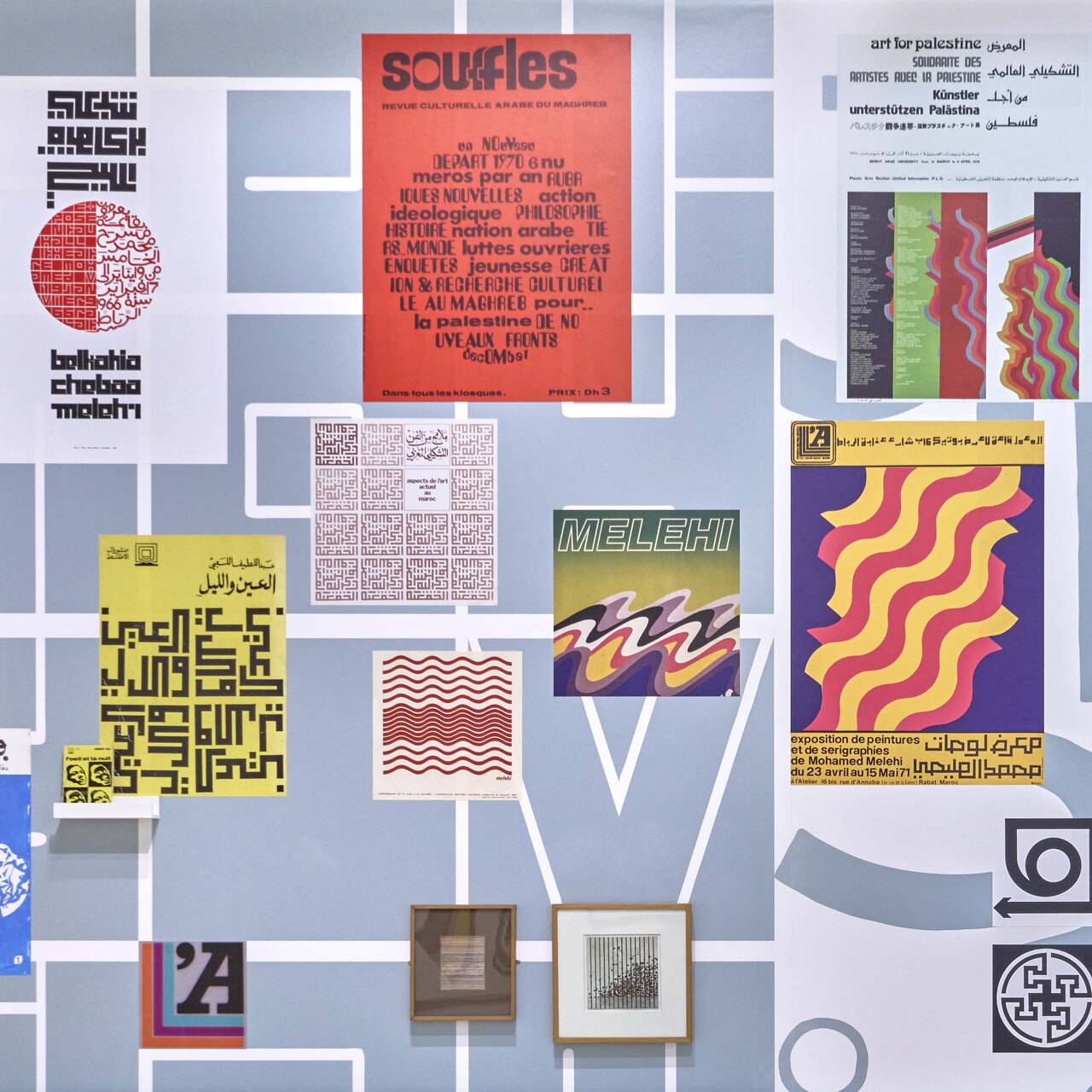

The end of World War I in November 1918 meant a break with the past, but also a new beginning for Germany. Around two million men had lost their lives on the battlefield, and now they were sorely missed in the labor force. By anchoring the equality of men and women in the Constitution of the Weimar Republic and giving both sexes the right to vote, women were suddenly offered completely new possibilities: They received better educational opportunities, could even study at an art academy. The professional image of the “young lady on the typewriter” was created and women became less dependent on men. What liberty!

With the end to the restricting corset came likewise an end to many inhibitions: Hems were shortened, ankles became visible, women wore feathers in their hair and danced the Charleston until the early hours, dressed in the “garçonne” look with tails and monocle, concealed their true gender, and practiced same-sex love. And because money lost value at an incredible speed during the inflation that lasted until 1923, people spent money like water and had lavish parties. The image of the “New Woman” was created; in 1932, Fritzi Massary sang about her in an operetta by Louis Verneuil: “I am a woman who knows what she wants, I have my pace, I have my style, I have my inhibitions firmly in my hand, a bit of emotion, a bit of reason.” It was an image that was also reflected in the art of the Weimar Republic, particularly in that of the “New Objectivity” movement.

Individuality in passing as it were

During World War I and shortly afterwards Expressionism still held the upper hand: We find distorted, exaggerated depictions of women in a subjective, transfigured view in Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Erich Heckel, Karl Schmidt-Rotluff and Otto Dix; among other things the artists wanted to portray dreams, emotions and social criticism. That was not the case in New Objectivity, which was already palpable from 1919 as a kind of “post-Expressionism”, but was only given the name it is known by today in 1924: When you pared back pathos and exaggeration what remained was the down-to-earth, intrinsic nature of the motif, a kind of sober and primarily emotionless stocktaking of what remained after a decade of war and inflation. There was an objectification of the depicted person, whose individuality is only barely visible yet simultaneously produces a universal type.

Especially in the depictions of the “new woman” artists did not bother with those traits typically thought of as female: And so “The Portrait of the Journalist Sylvia von Harden (Das Bildnis der Journalistin Sylvia von Harden)” by Otto Dix portrays the androgynous figure of a woman, who is sitting in a cafe with bobbed hair, monocle and cigarette corresponded to the image of the day of an emancipated woman – a woman who did not care less about the prevailing social notion of beauty and gender roles, and instead pursued her goals in a confident manner. “Ideally, the garçonne by Berlin definitions is a girl, who looks like a man, who looks like a girl, who looks like: Renée Sintenis,” writes Silke Kettelhake in her biography of sculptor Renée Sintenis, who with her boyish appearance and success as an artist turned heads in Berlin’s Bohemian world.

A palpable coolness

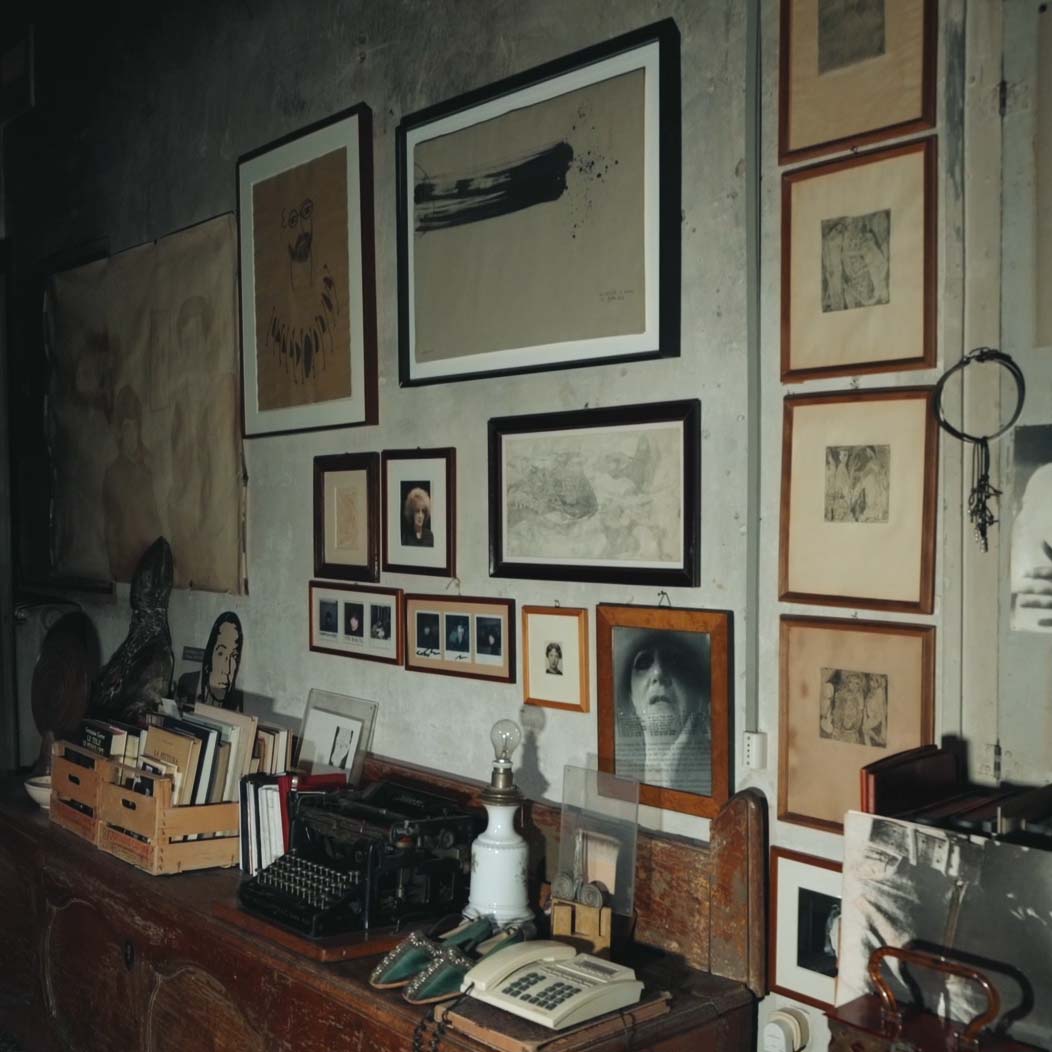

The portrait “Margot” painted by Rudolf Schlichter in 1924 also exudes a great deal of confidence. The famous prostitute appears tired but dignified, and above all ready to defend her profession with pride against her critics – such charisma is not, for example, to be found in the milieu studies by Otto Dix. In the 1920s, the ruthless gaze of the early Expressionists does not omit a single detail of the deteriorating, deformed and dissipated body of the aging woman. The city of Berlin not only brought with it a wild nightlife, but also meant anonymity and alienation, expressed in the images of New Objectivity as a palpable coolness. They show the “hard, unsentimental shell” people were obliged to develop in order to survive the dark days of the war.

The new gender roles also brought a change to the relationship between men and women, which was also frequently addressed by artists. From the depiction of women as loyal and caring wives, via the eager lover through to the morally weak, sex object available for money, in the paintings and drawings by male artists the changing “balance of power” is a frequent topic: The “Conquest (Eroberung)” by Rudolf Schlichter, painted around 1927, shows a woman in a negligée wearing pointed boots, standing on the back of a cowering man – the growing autonomy of women is also viewed with concern.

Where women met like-minded women

However, women expressed their view of the situation in the inter-War years differently. In particular Berlin artist Jeanne Mammen painted confident women who look out from the painting in a provoking manner, ready to face a world that is still dominated by men or to elude it all together in favor of same-sex love. The latter had – above all in the guise of sexual encounters between women – found their Eldorado in Berlin. Increasingly, meeting places come about where women could meet like-minded women, and (though this was still openly ostracized by society) could live out their inclinations. Jeanne Mammen was in the midst of it and painted tenderness between women from a clearly female perspective, while the other sex was automatically pushed into the role of observer. Studies by men on lesbianism, such as “Girlfriends (Freundinnen)” by Christian Schad, come over as cool and hackneyed – are especially objective.

The image of the “new woman”, her provoking abandonment of previously traditional roles and her newly acquired confidence are manifested in the Weimar Republic both as a blessing for the sex concerned but also as an attack on masculinity. This ends at the latest with the advent of the Third Reich, when emancipated women were ‘put back in their place’ and degraded more or less to a breeding machine and housewife – an image also portrayed in art.

DIGITORIAL

The free digitorial provides you with background information about the key aspects of the exhibition “Splendor and Misery in the Weimar Republic”.

For desktop, tablet and mobile