Fundació Pilar i Joan Miró on Majorca offers an insight into the work of an exceptional artist who valued simplicity just as much as the fantastical.

When we talk about the art space, we are generally referring to questions of presentation: white cube vs. public space, gallery vs. off-space. However, there is a different space entirely that exudes a far more mystical attraction, one without which the question as to the appropriate exhibition architecture would be wholly superfluous: the artist’s studio. Artists have themselves repeatedly focused their attention on this place; in 1855 Gustave Courbet painted “The Artist’s Studio” and let the world partake in it on two levels, namely as depicted protagonist on the overcrowded studio image and later as an observer of that very setting.

Beyond the canvas these insights are naturally rare. For during the work process artists must screen themselves off or at least carefully select the impressions and people that have access to their world. It is therefore not uncommon for artists’ studios to become accessible to the public only posthumously, if at all. A new opportunity to again experience the fascination of this pivotal place in the process of artistic creation will likely be presented at the latest in early March at the New York Armory Show. There visitors have the opportunity, as previously in London, to view a reproduction of Joan Miró’s studio on Majorca. Day tickets granting access to the show’s various exhibitions start at 45 dollars; long lines can be expected.

As though the pigments showed him special favor

That said, it remains a reconstruction, a very careful imitation, even though it does have real pictures and sketches and real furniture from the original studio. It may serve as a teaser however, an appetizer enticing people to visit the real spaces, hopes Joan Punyet Miró. The great painter’s grandson heads his grandfather’s foundation, nurtures his forbear’s artistic heritage and the studios dotted around at various locations. Miró particularly liked spending time on the Balearic island of Majorca; there are several buildings here in which he lived and worked.

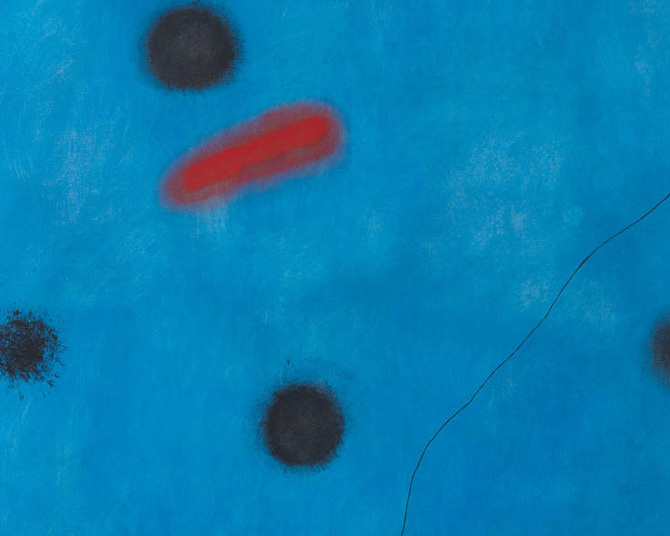

The tour begins in the café on the extensive complex, which sits above the small seaside resort like a fortress. The walls display a ceramic work, the template for which Miró once made for what is now the Terrace Plaza Hotel in Cincinnati. This one place alone is a concentrated reflection on so much about the artist: Miró’s penchant for large, even giant formats, his openness towards contract work (he loved the idea that as many people as possible would see his art), his unorthodox approach to themes and formats (from the sketch of every single compartment on the wall), the way he worked in series and of course those strong, bright colors, as though the pigments wanted to show him special favor.

An Egyptian cat goddess

On the opposite side hangs a picture of the young Joan Punyet, together with his brother and grandparents, Joan and Pilar Miró, at precisely this place. Today the grandson lives on the complex, above foundation and studio rooms, and you could hardly imagine a better guide through the sacred rooms than him. He remembers an anecdote about the carob tree on the way to the studio, or about life on Majorca during Franco’s dictatorship in general and chocolate production in particular, on the traditional Majorcan household paintbrushes that his grandfather liked to use for his paintings, and finally about the dead cat, which was at some point found mummified in Son Boter, the large studio building, after the artist had been away for some time. An Egyptian cat goddess: It was kept.

Speaking of Son Boter, the traditional 18th-century Majorcan farmhouse was located on the neighboring estate, which Miró bought in the late 1950s. He was intent on having more space for his works and so he made the owner at the time, a German-speaking woman who ran a guesthouse, a good offer. The painter left the old kitchen virtually untouched, and in the rest of the property too he preferred to work with the existing architecture and furnishings. He used the rough, sand-colored walls as a base for charcoal drawings, and the kitchen interior became a source of inspiration for him. Indeed, Miró was not afraid to use bric-a-brac and seemingly trivial items: What he liked, he added to his collection – regional folk art, found items, postcards and prints by artists he admired, even kitchen sponges can be found in Son Boter to this day.

The unofficial “Pollock Room”

His interest in the world, in the whole, was a universal one: “My grandfather was a believer, but he didn’t believe in a god – for him everything was divine”, explains Joan Punyet Miró. His artistic work can also be seen in this context: John Cage and Vincent van Gogh, Rimbaud and Duchamp, some were companions, but all of them inspired the artist. One room is unofficially called the “Pollock Room”; Miró admired the Drip Painting technique and used it in his own experiments. The seemingly inexhaustible creative drive, this curiosity about everything new (and what can be more undefined than the bare canvas?) becomes manifest in a highly symbolic way on the upper story of the building, which is normally closed to visitors: Here there are as many as a dozen canvases rolled up in a corner, and next to them countless stretcher frames with canvases on them ready to go. Even in his mid-80s he still had ambitious plans.

The Sert Studio, which the painter had moved into a few years previously, constitutes an architectural counterpoint to the Majorcan farmhouse. Miró wanted to get away from the city, where studio space was limited. Before moving to Majorca he commissioned architect Josep Lluís Sert with the design of a studio house. He was delighted with the spectacular building with its geometric shapes and bright colors – he had finally found an adequate studio where he had sufficient light (thanks to indirect daylight via the roof) and above all space. The photos of Sert Studio, of the painter surrounded by his pictures, became world famous. Here too a lot is unfinished, work in progress: Numerous canvases are unsigned, there is still paint clinging to the brushes.

Everything as it should be

When Miró was working, visiting his studio would have been unthinkable. Indeed, he needed absolute quiet; even his beloved children and grandchildren had to stay outside. As Joan Punyet recalls, his grandfather didn’t much like music in his studio either. And so the visitor inevitably becomes a little like a voyeuristic intruder, who can never be quite sure whether the artist might indeed suddenly stride into the room to make sure everything is as it should be.

This need by no means signal the end of the visit. In 1992 the grand Moneo Building was opened, designed by the Spanish architect of the same name and which today shows temporary exhibitions of the painter’s works – whereby Miró expanded the concept of painting at a very early stage to include all kinds of materials and techniques, to which the exhibitions here firmly attest. The foundation complex is not designed to be a lifeless open-air museum, which is why, notwithstanding all the necessary preservation measures, Miró’s print workshops for instance are used for summer workshops. Here, young artists can produce lithographs in precisely the place where the artist himself worked just a few decades ago.

The luxury of space

Of course the time then comes when one has to leave the Fundació, through the stone entrance, behind which there is no rural idyll, no expanse of fields, but apartment blocks built all the way up to the complex, at whose windows rags instead of net curtains waft in the wind. The luxury of space: Unlike the overall environment, the product of the last few decades, the spaciousness of the rooms that Miró found so important for his work is particularly striking. But who knows, perhaps the painter would have liked this – less aesthetic, to be sure, but as an expression of the reality of life that ultimately interested him at least as much as the fantastical realm of ideas.