SELMA SELMAN's artistic practice cannot be described as site- or situation-specific; rather, it seems to deal with the self and its constant transformation. May we instead speak of a self-specific practice? What does this mean and how is it expressed in her works?

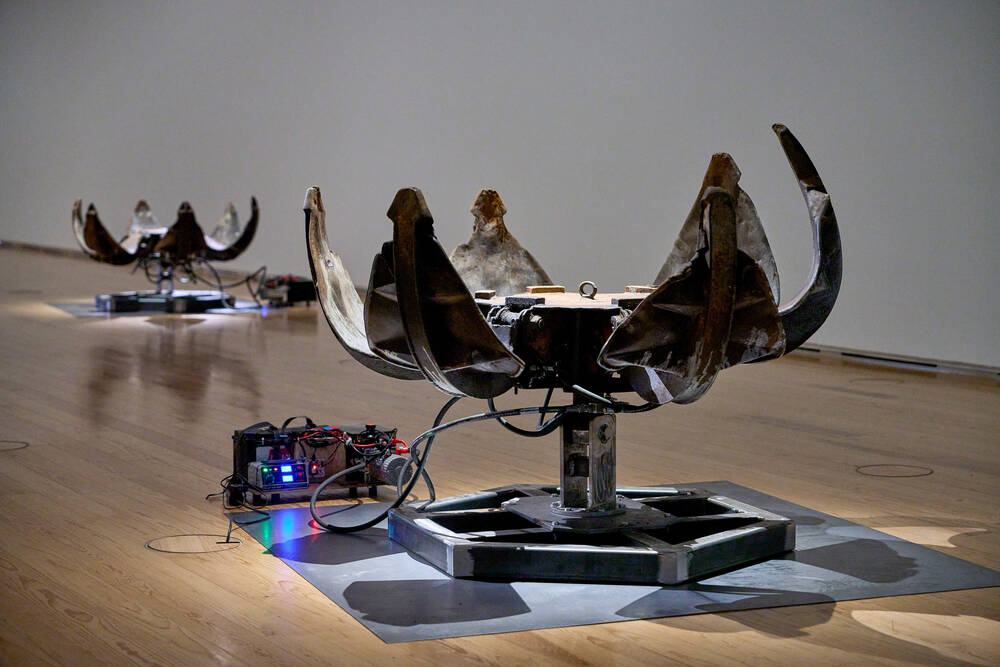

For her solo exhibition at SCHIRN, Selma Selman instills mechanical life into multi-tine grabs to make them open or close like flowers; in a video, she re-enacts the crossing her mother performed during the war in Bosnia on a bridge that was covered with dead bodies; at the height of her own forehead, she drills into the wall a nail coated with the gold she extracted from computers.

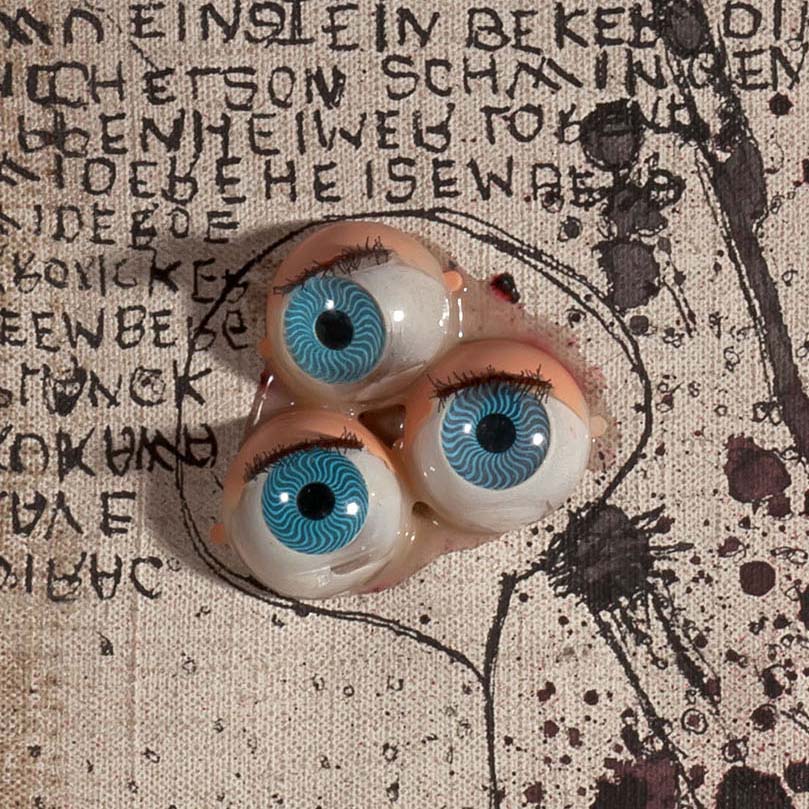

Selman’s artistic practice is inspired by her own experiences, daily scenes of Bosnia and the life of her family, revealing by extension the tensions surrounding topics of identity, stereotypes and expectations. The discrimination her community faces, as well as the obstacles she encounters being a woman of Roma origins from Bosnia condensate in her art into questions of labour, value, inequality and segregation. Her works often take the form of harsh and ironic reflections on her position in the whirlpool of global capitalism, sensitive and eerie text-based confessions or disquieting depictions of female body parts elongated in a spidery way. However, in order to understand the complexity of this bold, defiant, singular artistic voice that both embraces and blasts stereotypes with baffling permeability, this definition might be simplistic.

A self-specific practice

Selman’s practice can neither be qualified as site-specific (a practice which relates to the idea of space, takes into account the characteristics of a particular location and develops in close interrelationship with it) nor as situation-specific (a practice which explores and reflects upon a set of circumstances, a state of affairs, and therefore relates to events in time), but – may we say so? – as self-specific. If the term ‘self’ is firstly understood as identity, character, essential qualities, and secondly as a communal, social and biopolitical context in which the self evolves, then ‘self’ does not reduce to a set of innate characteristics and to origin that determines it; It includes acquired qualities, as well as the idea of evolution, imagination, goal and future. In her artistic practice, Selma Selman interweaves both these realms into an elastic fabric that she shapes and wears freely. She both is her present self and her possible future selves in a transformative self-specificity.

“I gave myself value and created myself […] I make my own narratives” – does she say in a video interview from 2022 at the occasion of her solo exhibition at Kunstraum Innsbruck.

Indeed, Selman entitles and considers many of her works as “Self-portraits”, should they take the form of drawings, performances or paintings. These works condense different layers of Selman’s self, allowing us to catch a glimpse of her past experiences, her present situation, her possible or imagined future, and at times, a fictional-realistic blend or superposition of these, which, unlike the comparably self-specific art practice of Joseph Beuys, does not culminate in myth. What links “Self-Portrait I“ (2016), a performance in which she destroys a washing machine with a fire axe in the streets of Rijeka wearing a flowery dress, her painting “I’m a Lady like my Mother“ (2020) in which her own traits and those of her mother indiscernibly melt, and her project “Motherboards“ (2023-ongoing) in which she and male members of her family destroy CPUs to extract their motherboards and ultimately, the gold it contains?

Selma Selman, "Self-Portrait I", 2016, Image via pinterest.de

I gave myself value and created myself […] I make my own narratives

“Transformation is at the core of my practice: scrap metal into gold, stigmatised labour into prestigious labour, incapacity into invention” – she states in a recent interview to Frieze on the occasion of her exhibition “Her0“ at Gropius Bau in Berlin (2023-2024). In order to do so, she herself also keeps transforming, undoing and weaving again the fabric of her discursive visual production in a permeability between mediums allowing her to ask questions in ways they were never put and shape statements in ways they were never screamed.

Constant transformation

In the film “Crossing the Blue Bridge“ (2024), Selma re-enacts the memories of her mother crossing a bridge with Selma’s sister during the war in 1994 in Bihać, her native town in Bosnia. The mother covered the eyes of her child so that she does not see the dead bodies scattered on the bridge, while wind blew her hair in her eyes during the crossing, which, taking only three minutes, seemed never-ending. In the 27 eerie and insistent minute film, shots are superposing and overlapping in a loop blending reality and fiction; the wind keeps blowing Selma’s hair in her eyes, reincarnating her mother but also her sister whose eyes were covered by her mother. She is both the mother and the child, transforms into them, and then back into herself in a staged ambipotency in which the cathartic re-staging and the transcendence of a traumatic event indiscernibly melt.

“Motherboards (Golden Nail)“ is a piece pertaining to a multi-layered large-scale project comprising a performance, a video, four portraits painted on Mercedes car hoods, an installation of destroyed computer CPUs and a nail coated with gold. Motherboards are the central parts of computers that connect all other components – processor, memory, hard drive and video card – and therefore act as their “mothers”. Metaphorically, Selman draws a parallel between motherboards and Roma women who, by belonging to men as wives and mothers, remain invisible in society, as motherboards inside computers. These boards are not only a metaphor, they also serve as raw material from which the artist extracted gold with a non-toxic technique she elaborated on the basis of a revived, thousand-year-old process. With the gold obtained from 200 motherboards, Selman coated one nail, as a symbol of Roma women’s essential role in their family, yet invisible social status.

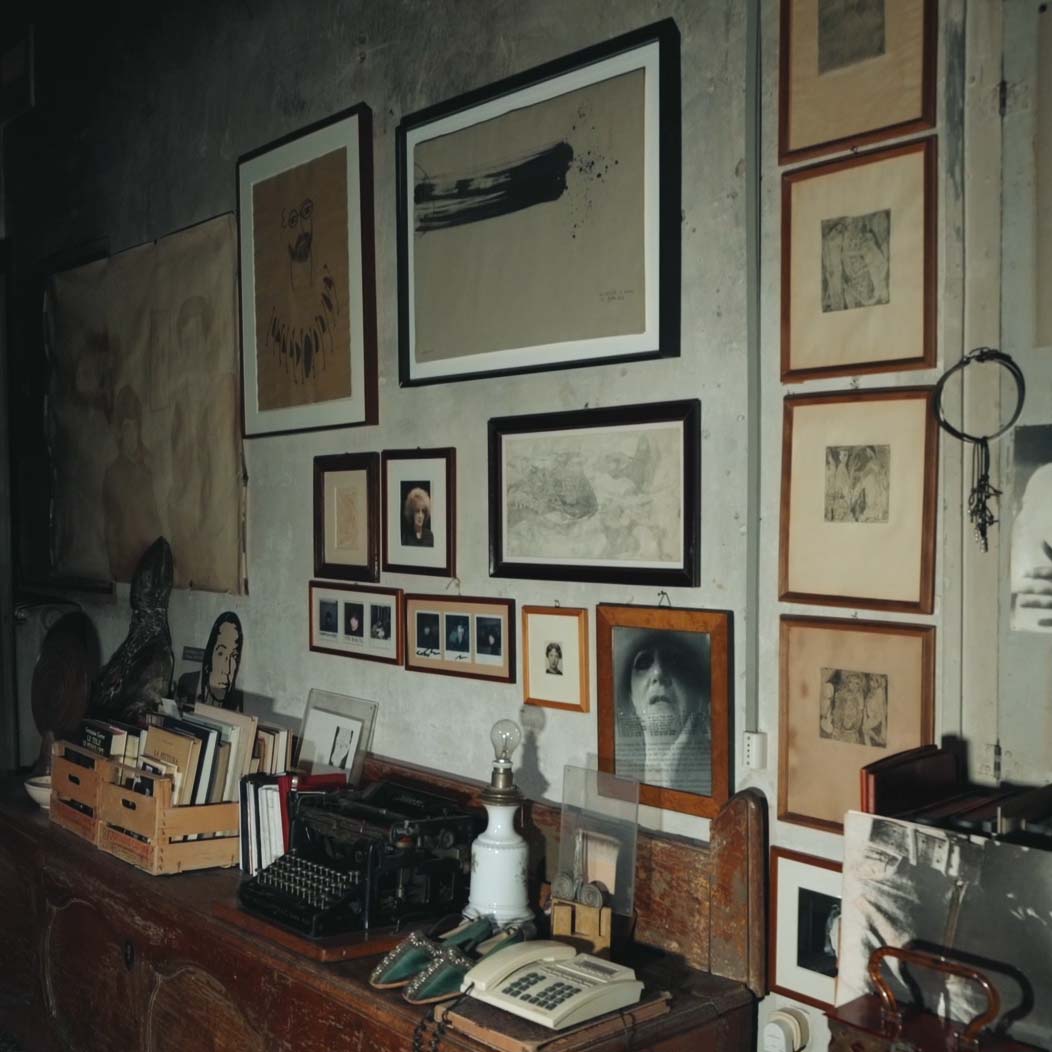

Selma Selman, "Motherboards (A Golden Nail)", 2023. Open Studios, Rijksakademie van beeldende kunsten, Amsterdam, Photo: Sander van Wettum, image via neroeditions.com

Selma Selman, "Motherboards", 2023, performance, Krass Kultur Crash Festival, Hamburg. Courtesy: the artist; photo: Mario Ilić, Image via frieze.com

“We will not be free until we’re worth more than gold” – does she repeat in her performance “Motherboards“, referring to the importance of the precious metal in Roma culture, but also the fictional power of alchemy.

To bloom in a Loop

Turning scrap metal into art, transforming discarded machines into gold, transcending stigmatised labour into value; The artist’s intention unfolds both in an (up)cyclical and spiral way. Drawing upon her identity, origins and biopolitical context, she gives back to her own community in a transformative economy of inspiration. Empowering Roma girls through education with her project “Get the Heck to School” or transmitting the knowledge of extracting gold from scrap metal to her community in order to lift them out of poverty, her activism is fuelled by the power of transformation and aiming at turning stigma into recognition and legitimacy.

Selma Selman’s intention is twofold: to reverse the stigma surrounding the Roma community and reappropriate territories that have historically been masculine: technology, money, writing and speech. Nevertheless, her fight cannot be massified; her freedom does not express in the masses of oppressed minorities, nor in her community specifically. It is not in her fight against oppression that her freedom unfolds truly, but in her self-specific, transformative creativity, in her constant visual and conceptual metamorphosis as well as the way she succeeds to bloom and awaken as a different creature again and again.