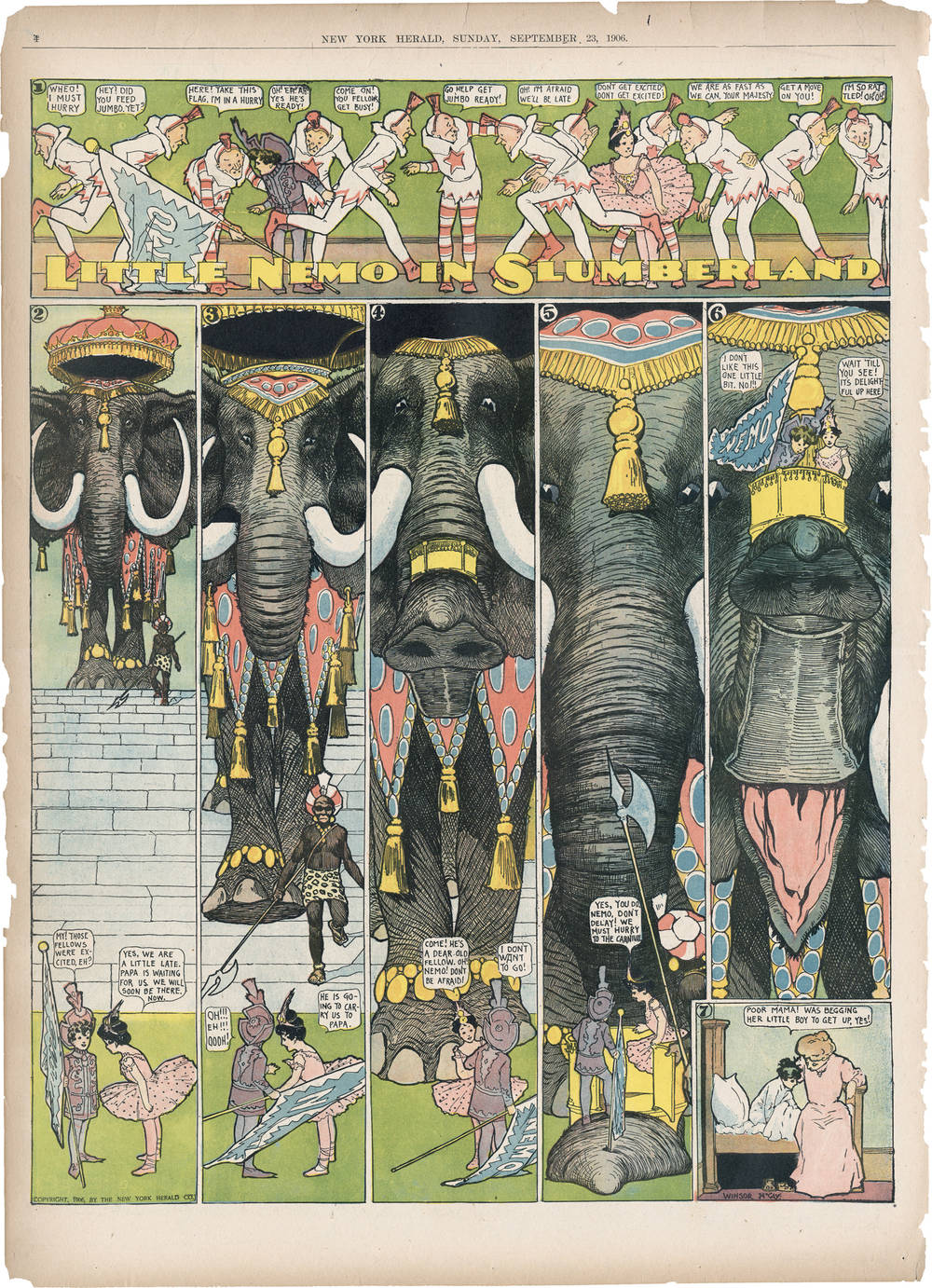

Dream, imagination and illusion: Winsor McCay pushed the boundaries of the comic format, regularly sending his hero Nemo to the end of the world and far beyond. Nemo’s marvelous adventures last until he wakes up from his dream with a start.

With “Little Nemo in Slumberland”, cartoonist and illustrator Winsor McCay (1836-1934) managed to create a visually impressive and extremely comprehensive work. Nemo’s adventures were printed over a full color page every Sunday between 1905 and 1911 in the New York Herald and became McCay’s best known comic series alongside “Dream of the Rarebit Friend”. They were also his most widely-circulated works, with McCay producing a total of 549 pages i during those years. In 1908 “Little Nemo in Slumberland” premiered as the most expensive and elaborate Broadway show that had ever been produced.

The figures actually begin to dance

After more than 100 performances in New York, the show went on tour around the country. Three years later McCay produced an animated short film titled “Little Nemo, also known as Winsor McCay, the Famous Cartoonist of the N.Y. Herald and His Moving Comics”. Here the illustrator refers to himself as creator of Nemo’s dream world and is presented as “the first artist to attempt drawing pictures that will move” in the opening titles. And indeed his figures do actually start to dance and skip after he has brought them to the paper with pen and ink.

McCay hereby tested and expanded the formal boundaries of the comic and experimented with arrangement and composition. He allowed his figures to break out of the confines of the image and devour the letters making up the title. The panels themselves were also freed of their static structure. By employing flexible arrangements and varying dimensions, McCay injected greater dynamism into his narration and played with optical illusions.

Tree trunks become rhinoceros horns

Thus scenarios stretch over several panels. Not infrequently, kaleidoscopic patterns emerge from icy landscapes, armies of soldiers or palace architecture. In terms of both form and content, dream, imagination and illusion are the determining themes in “Little Nemo”. And just as tree trunks become rhinoceros horns, a little girl is transformed into an old witch, or the pillars of the palace suddenly change into a dense forest, Nemo always wakes up in the final panel, either awoken by his parents or by falling out of bed.

With Lewis Carroll’s “Alice in Wonderland” (1865) and Sigmund Freud’s text “The Interpretation of Dreams” (1900, the English translation appeared in 1913), dreams became an important topic in cultural and scientific discourse around the beginning of the twentieth century and, with Surrealism, also a source of inspiration for fine art. The examination of the subconscious, the absurd and the fantastical offered insights into suppressed desires or disturbances, as in the case of psychoanalysis, or made it possible, as with Surrealism, to tap into new forms of perception and experience.

The boundaries between image and life

The ambivalent fascination with dreams is uniquely expressed in McCay’s work. Nemo frequently wanders through his disturbing dream worlds much more timidly than his female companion, the adventurous princess, and in the end wishes he didn’t always have bad dreams.

Ultimately, in “Little Nemo in Slumberland”, it is not only the boundaries between image and life that are fluid. Dream and reality also overlap and bring Nemo to places that appear to exist outside of space and time. As the year 1906 comes to an end, Nemo and the princess find themselves in a bleak landscape. “It looks horrible here!”- “This is the end of the world!” Here they meet an old man with a long beard and a torn robe. “Don’t look so sad, Mr. 1906. You did your best!” Old Father Time appears in a carriage and hands them a small, blond baby: “Here is the new little 1907. There, you take him” – “Oh! You little darling! Look Nemo, it’s the new year!”