Pop, Funk and anti-heroes: The SCHIRN presents the idiosyncratic painting of Peter Saul in a major survey exhibition.

From June 2 to September 3, 2017 the SCHIRN is presenting an extensive survey exhibition of the work of the American painter Peter Saul (*1934 in San Francisco, California). Long before “Bad Painting” became a central concern in contemporary art, Peter Saul deliberately offended good taste. Beginning in the late 1950s he developed his highly individual idiom blending Pop Art, Surrealism, Abstract Expressionism, Chicago Imagism, San Francisco Funk, and cartoon culture, one in which he managed to address complex political and social issues.

Saul shares with Pop Art an interest in the commonplace, in consumer society, and the cheerful pictorial worlds of the comics in glowing, appealing colors. Yet his work is also associated with the aesthetic strategies of the California counterculture. He produces an almost irate kind of painting when depicting the darker sides of the American Dream. In it he combines exuberant humor and playful but harsh criticism of the system. He makes use of jokes, slapstick, puns, comedy, and persiflage, and often crude humor in his caricature-like attacks on American high culture.

They tend toward exaggeration

Apart from the major artistic schools, Saul developed an extremely idiosyncratic oeuvre. Never really associated with any group or movement, he has been painting in his own way despite changing artistic fashions for more than fifty years. Saul’s paintings tell stories, tend toward exaggeration, and resist unambiguous interpretation. The SCHIRN has brought together roughly sixty works by this hitherto little noticed “artists’ artist,” among them groundbreaking groups of works like his "Ice Box Paintings", his comics narrations and Vietnam paintings from the 1950s and 1960s, as well as never exhibited drawings and selected late works from the 1980s to the 2000s.

Peter Saul began painting in one of the most exciting periods in American art history. In the mid-1950s a young generation of artists broke with the rules and values of Abstract Expressionism. They discovered a new parallel between art and life, one in which the traditional work of art had seen its day. In their engagement with the everyday they rejected middle-class notions of originality and uniqueness. Pop established itself as the leading culture, became a global phenomenon, and found its best-known representatives in Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Jasper Johns, and Robert Rauschenberg.

As a unique feature

Peter Saul’s paintings were often categorized as Pop Art. But despite similar motifs and an interest in everyday culture that link his works to Pop, they clearly diverge from it. The SCHIRN exhibition begins with his early "Ice Box Paintings" from the late 1950s and early 1960s. In postwar society the refrigerator was a symbol of prosperity and economic growth. Saul’s paintings present a chaotic excess of consumer goods, and tell of the promises they represent. At the same time they are settings for narratives of mass and consumer culture: in a weird formal language Saul packs whole lives into these Ice Boxes. With their complex pictorial structure they also have a certain similarity with the dynamic gestures in the Abstract Expressionism of a Willem de Kooning. In his painting Saul combines contrasting stylistic directions like Pop Art and Abstract Expressionism, and as a unique feature adds to his motifs the telling of stories.

As the characters in his narrations the painter frequently chose popular comic-strip heroes like Mickey Mouse, Superman, or Donald Duck. They were figures everyone knew, and with whom the public identified. In his works from the 1960s he used his comic characters in dealing with serious political issues. In the painting "Mickey Mouse vs. The Japs" (1962), for example, he lets a tiny Mickey Mouse, representing the average American, take on the Japanese. In doing so he was hardly thinking of the United States as a melting pot, but rather alluding to the cleavages and conflicts between cultures. In addition to Mickey Mouse, Superman—to this day the best known of all the superheroes—frequently turns up in his works. But Saul deconstructs the role of the flawless hero; he pictures him in banal settings, and concentrates on his darker moments of defeat.

Superman flattened by a monstrous steam roller

From this series the Schirn is showing "Superman and Superdog in Jail" (1963), in which the hero is sitting in a torn costume in jail, while below him Superdog is eagerly drinking from a toilet bowl; also "Superman’s Punishment" (1963), in which the hero is being flattened by a monstrous steam roller, his leg bent in the wrong direction, his arm squashed, and his face an ashen gray. In a whole series of other paintings Saul shifts to the main focus of his narratives and illustrates crimes and violence. He pictures a "Killer" (1964), a "Woman Being Murdered" (1964), a perpetrator who after a Sex Crime (1964) wants to dispose of the woman’s corpse, or a group of bank robbers, the "Super Crime Team" (1961–62). Saul illustrates where such crimes can end in the work "Crime Doesn’t Pay" (1963)—named after a popular American comic book series—and in "Man in Electric Chair" (1964), in which gangsters and villains are confronted with the law.

In the mid-1960s Saul increasingly included political messages in his works. His proximity to Funk Art, especially Junk Culture, a specific genre prominent on the West Coast and especially in San Francisco, is obvious. His artistic position, with a preference for everything bizarre, sensual, informal, and often even ugly, is visible in his works presented in the legendary Funk exhibition in 1967 at the University Art Museum in Berkeley. Funk Art was the expression of a strengthening counterculture with a passionate disdain for the enticements of consumerism, for bigotry, and for the world’s rigidity, vulgarity, and injustice.

Criticism of the political system

In 1965 Saul was one of the first painters to turn to one of the darkest chapters in American history with his Vietnam paintings. The SCHIRN is presenting "Yankee Garbage" (1966), "Vietnam" (1966), and the main work from this group, "Saigon" (1967), in which Saul takes a stand and expresses his rage at such atrocities as the torture and sexual violence perpetrated by the American military in Vietnam. Here too the artist employed the language of comic books: all the figures are caught up in a chaotic jumble, garishly colorful, and overdrawn. In these works one sees both a very dark, sarcastic humor and biting criticism of the political system.

In addition to subjects like the Vietnam War and the sexual exploitation of women, Saul deals in his works with racial conflicts and social discrepancies between poverty and wealth. The SCHIRN is presenting some of his most meaningful paintings, like "The Government of California" (1969), in which Saul stages a showdown between good and evil beneath the Golden Gate Bridge: the ultra-conservative governor Ronald Reagan against the human rights icon Martin Luther King Jr. In addition to King, Saul repeatedly painted the human rights activist Angela Davis. In the painting "San Quentin 1 (Angela Davis in San Quentin)" (1971) she is seen naked in front of the prison gates, being tormented by three little pigs named “Justis,” “Munny,” and “Powur.”

Contemporary American issues

In this work Saul’s love of word play and disdain for proper orthography and semantics is obvious. Violations against linguistic rules run through his entire oeuvre. Reagan returns as a motif in 1983: in "Ronald Reagan in Grenada" Saul pictured the former Western hero and then president of the United States as a dark anti-Superman wildly taking potshots with dollar bills in his hand. To this day Peter Saul’s painting deals with contemporary American issues, as in his "Bush at Abu Ghraib" from 2006.

The film to the exhibition: Hans Haacke. Retrospective

A legend of institutional critique, an advocate of democracy, and an artist’s artist: The film accompanying the major retrospective at the SCHIRN...

Non-human living sculptures by Hans Haacke and Pierre Huyghe

In his early work, HANS HAACKE already integrated animals and plants as co-actors into his art. In that way he not only laid the foundations for a...

CURATOR TALK. CAROL RAMA

SCHIRN curator Martina Weinhart talks to Christina Mundici, director of the Carol Rama Archive in Turin, editor of the first Catalogue Raisonné and...

Freedom costs peanuts

HANS HAACKE responded immediately in 1990 to the fall of the Berlin Wall and turned a watchtower into art.

The film to the exhibition: CAROL RAMA. A REBEL OF MODERNITY

Radical, inventive, modern: The film accompanying the major retrospective at the SCHIRN provides insights into CAROL RAMA's work.

Now at the SCHIRN: Hans Haacke. Retrospective

A legend of institutional critique, an advocate of democracy, and an artist’s artist: the SCHIRN presents the groundbreaking work of the compelling...

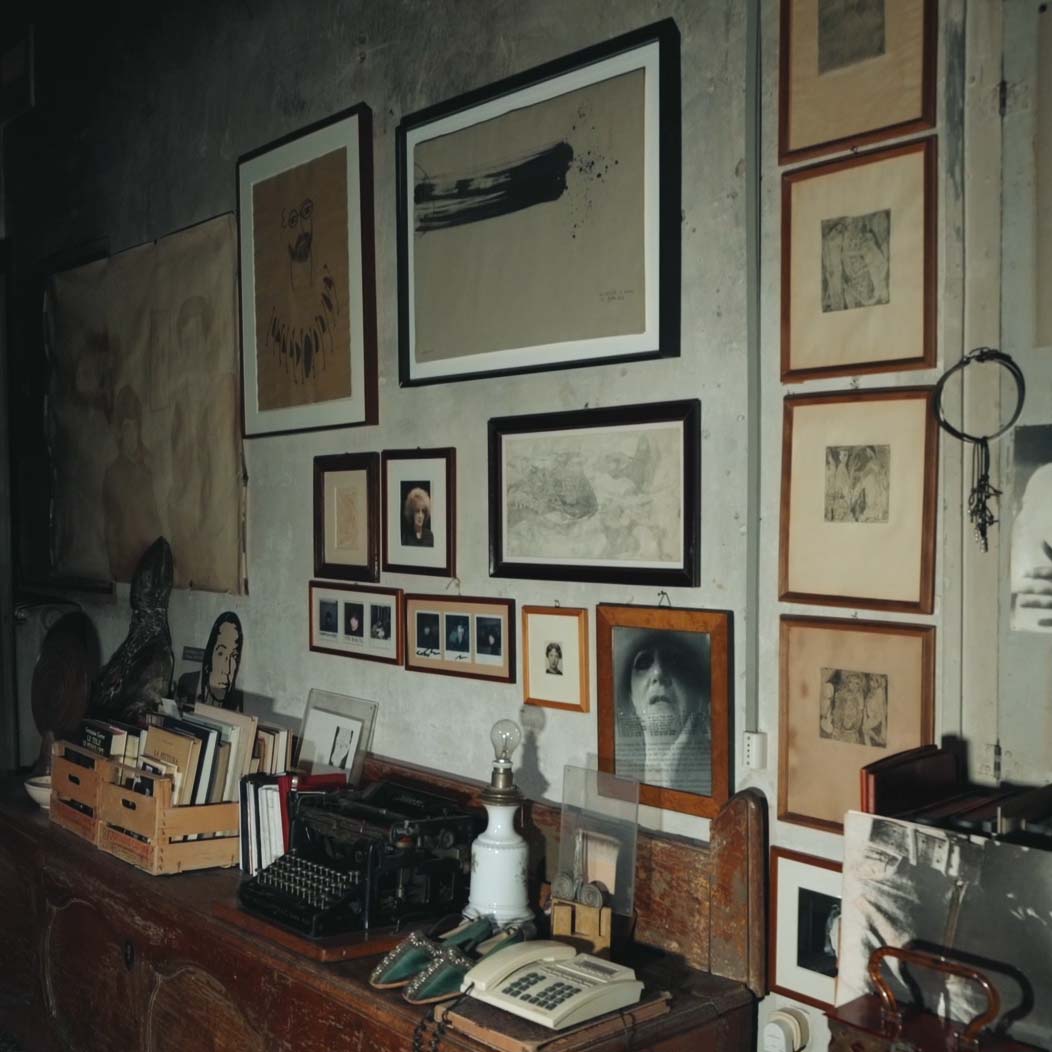

Carol Rama’s Studio: A nucleus of creativity

CAROL RAMA determinedly forged her own path through the art world. Her spectacularly staged studio in Turin was opened to the public only a few years...

PANEL: POLITICAL ACTIVISM BY SELMA SELMAN

Hosted by Arnisa Zeqo, Amila Ramović and Zippora Elders speak with the artist Selma Selman about her artistic career, the exhibition SELMA SELMAN....

Now at the SCHIRN: Carol Rama. A rebel of Modernity

Radical, inventive, modern: the SCHIRN is presenting a major survey exhibition of CAROL RAMA’s work for the first time in Germany.

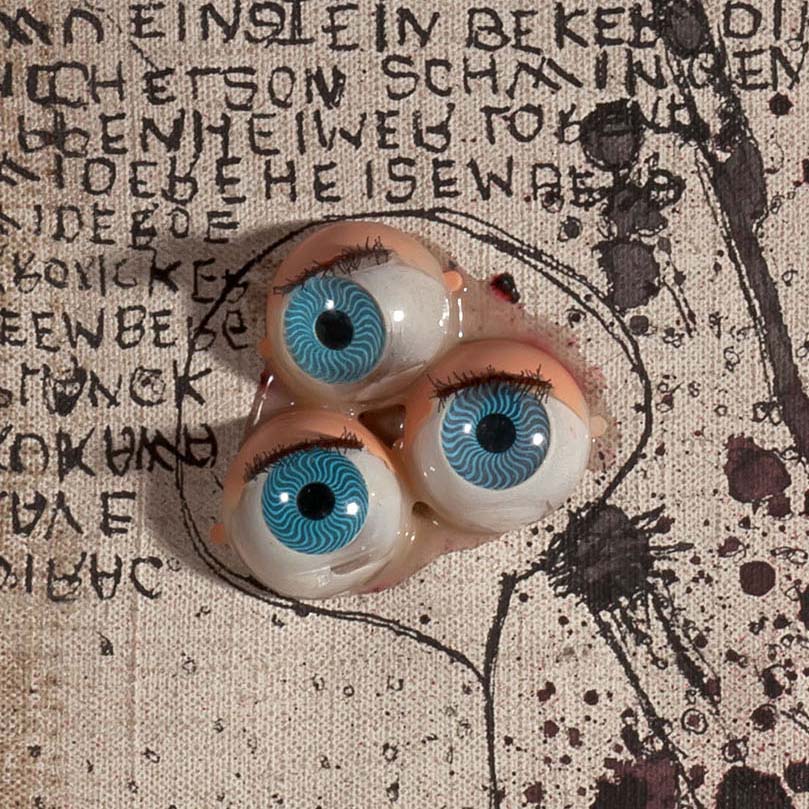

Carol Rama in 10 (F)Acts

CAROL RAMA was one of the most provocative female artists of the 20th century. With her explicit depictions of sexuality, physicality, and tabooed...