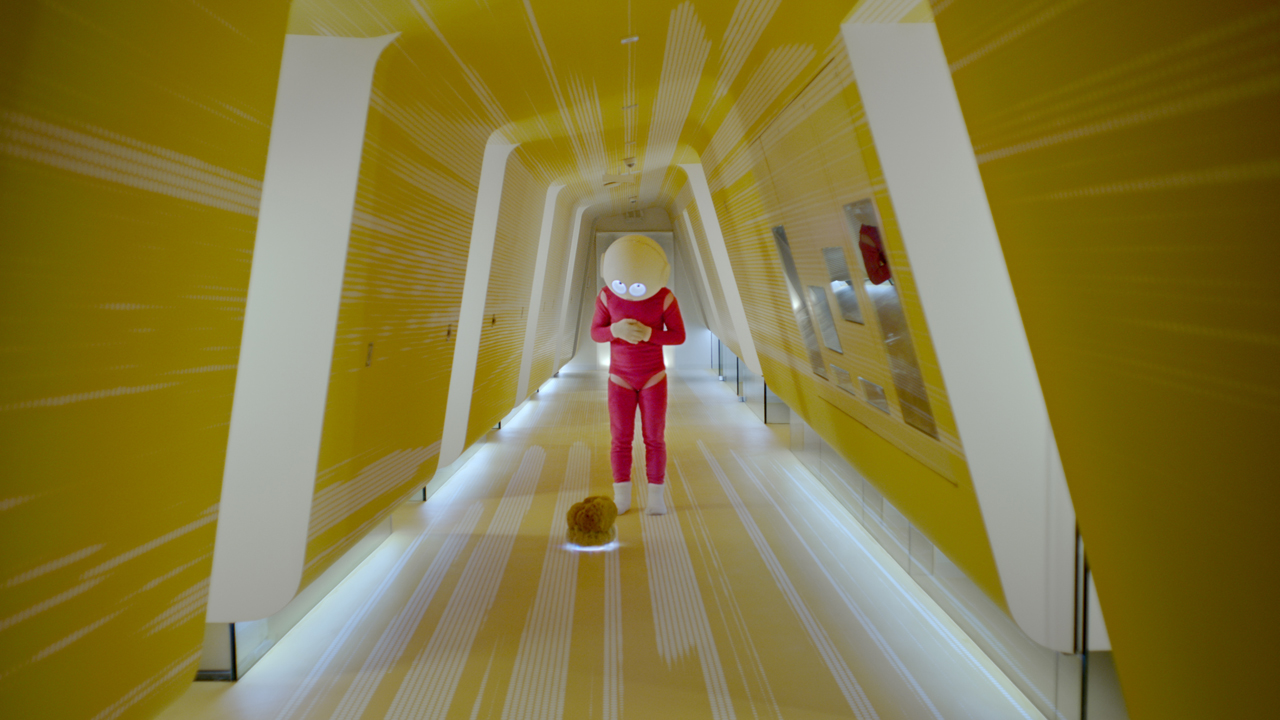

Between thing and being: In his film shown in the December DOUBLE FEATURE, the artist Paul Spengemann documents a creature from an in-between world.

What exactly distinguishes a living being from a thing? The fact that it consists of cells that are separated from the outside world by biomembranes? The ability to self-reproduce? Metabolism and genetic variability? Intelligence? You can choose to be more exclusive (awareness!) or more inclusive (a being that somehow is able to move) and yet ultimately end up facing questions such as whether viruses are living beings, or whether artificial intelligence ever counts as such.

This still says nothing, however, about abilities, of whatever kind: The Biological Cybernetics research group in Bielefeld demonstrates, for example, how something highly complex like a robot is still, in the truest sense of the word, lagging miles behind something apparently unremarkable like a stick insect. The researchers are meticulously analyzing the insect’s gallant, sure-footed locomotion and are hoping to be able to apply the operating principles to the machine’s movement. Paul Spengemann’s “Walking Stick” also presents viewers with a stick insect – or is it a robot after all?

Thirteen twigs in total

At the beginning of Spengemann’s work all we see is a sun-lit room and a few plants. Is that something rustling in the branches? What follows is a subjective tracking shot through the stems of the plant without us really knowing exactly what perspective is being adopted here. Eventually the camera appears to have recognized something under the radiator in the room; gingerly zooming in, it ultimately identifies a stick insect. This initially remains motionless, as if caught, but then climbs adventurously onto the camera lens. It is at this point at the latest that we realize this is not a “real” stick insect.

The legs are held to the body as if by an invisible hand, and the creature has no face or antenna. Spengemann took the individual parts of the stick insect from the plant in his room, 13 twigs in total, and these dead parts of a living being, the plant, were given new life in digital form. Like countless YouTube amateur wildlife filmmakers, the camera tries time and again to capture the dead yet lively being, by day and by night, complete with loud camera zoom noises on the soundtrack, as well as the creaking and rasping noises of the apartment.

The universe, one’s own four walls

“Walking Stick” could be viewed as a form study of a film genre, namely (amateur) nature documentary films, but nature and documentation do not feature at all here. Brought to life digitally by Spengemann, the dead twigs mutate into the “walking stick” the ambiguous title refers to, a stick to help you walk, and wander in a carefully planned and programmed way through their set universe, the four walls that surround them.

In the work, the protagonist, which continually disappears in the surroundings, is shown once in slow motion on the floorboards, where it performs a choreography of letters: “Oh dear” the stick insect, which in the animal world is classified as a ghost insect, forms with its body. Is this a case of a being becoming aware that it is a thing, or rather a thing become aware of that it is a being? Ultimately the camera is no longer able to find the animal and the gaze falls on the desk, also made of wood, while the ticking of a clock gets louder and louder.

Thoroughly normal life

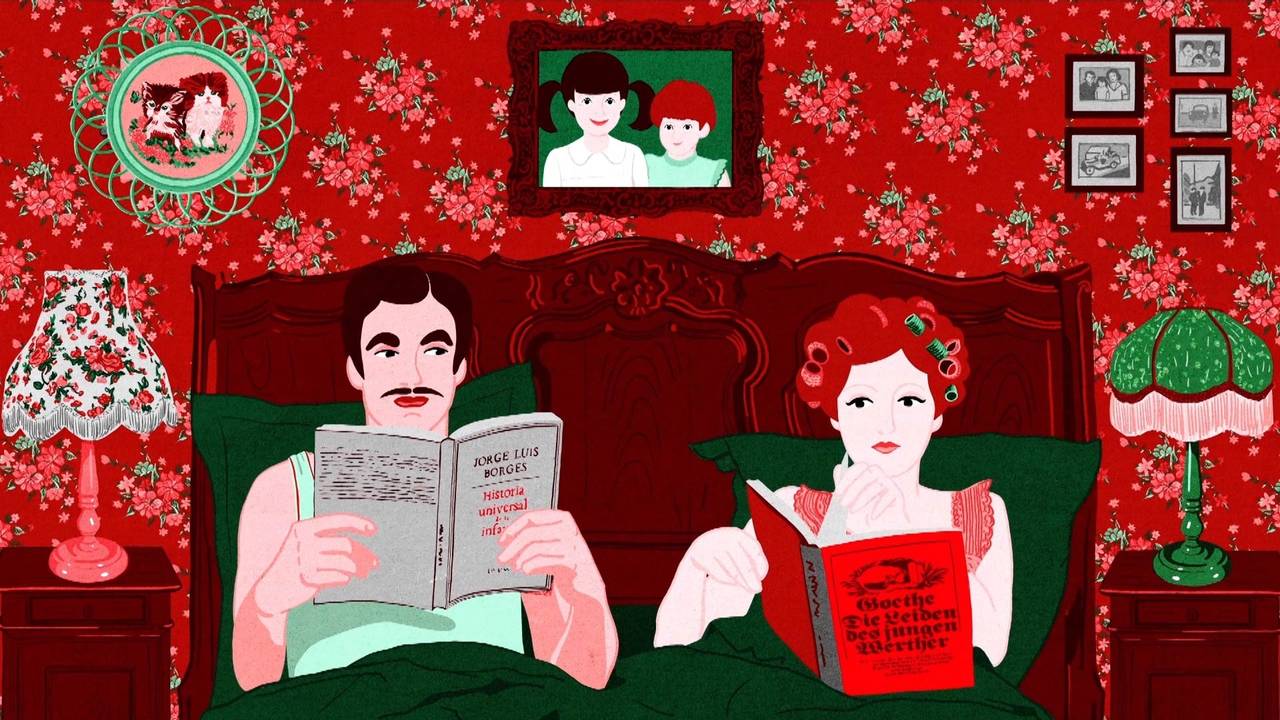

Also for Israeli filmmaker David Perlov (1930-2003) highlighting one’s own universe, and perhaps that of others, began in his own living room. “Yoman” (“Diary”) is a kind of journal, in which Perlov initially documented the period 1973 to 1983 on film, and then continued in further instalments up to 2002. In the beginning the director himself is heard on the soundtrack: “I want to start filming, by myself and for myself. Professional cinema does no longer attract me. To look for something else. I want to approach the everyday. Above all in anonymity.” Perlov begins in his own living room: He films his family, films through the window looking out onto the city, films thoroughly normal life. He continually comments on the image, narrating laconically that he now has to decide whether to film the soup or whether he’d rather eat it himself. He wrangles with his detached position, but ultimately heads out into the world with his camera after all.

The cinematographic diary of the years 1973 to 1983 covers a total of 330 minutes. It is bookended by two military conflicts: the Yom Kippur War of 1973 and the Lebanon War of 1982. As much as Perlov focuses on private, ordinary, everyday matters, there is no way to escape war, which penetrates daily life and indeed becomes daily life. Via television it penetrates living rooms, and with his camera Perlov captures a window on the world from his living room.

At the same time, the filmmaker processes his own history, following his daughters as they grow up, meeting Claude Lanzmann and Klaus Kinski, observing everyday life in Tel Aviv, travelling to Paris, where he lived for a long time, to London, and eventually to Brazil, the country of his birth. “Yoman” is an astonishing work, in terms of length and intensity, the spontaneity of the snapshots and in the pigeonholing and considered background commentary. Perlov portrays in detail his own life, both private and political, and thus at the same time creates a chronical of crisis-ridden democracy in the Middle East.

David Perlov, Yoman, Image via filmfesthamburg.de

At the mercy of waiting

Artist Bani Abidi is dedicated to the dark absurdities of everyday life. In her video work "The Distance from Here" bureaucracy takes over and waiting...

“Please don’t make a film about Godard!”

A film about filmmaking sounds a bit meta. But Kristina Kilian’s video work takes us on a ghostly journey through Godard’s Germany after the fall of...

Black is not a Color

In a film series, Oliver Hardt combines the themes from Kara Walker’s work with the perspectives of Black people in Germany. In conversation with...

How do we Remember?

In which places does history become visible? And what do we remember at all? Maya Schweizer begins her search for clues in the sewers and slowly feels...

Film highlights from South and North America

How can we break with the power relations of the past and create a decolonial future? A look at the representation of Indigenous women in film.

Must See: The World of Gilbert & George

Eccentric, fascinating, repulsive, entertaining and full of symbols: “The World of Gilbert & George” is a collage about the artifice of everyday life...

Spring is coming, and so is Magnetic North

For the first time in Germany, principal works from Canada’s major collections are on view at the SCHIRN. At the same time, the exhibition examines...

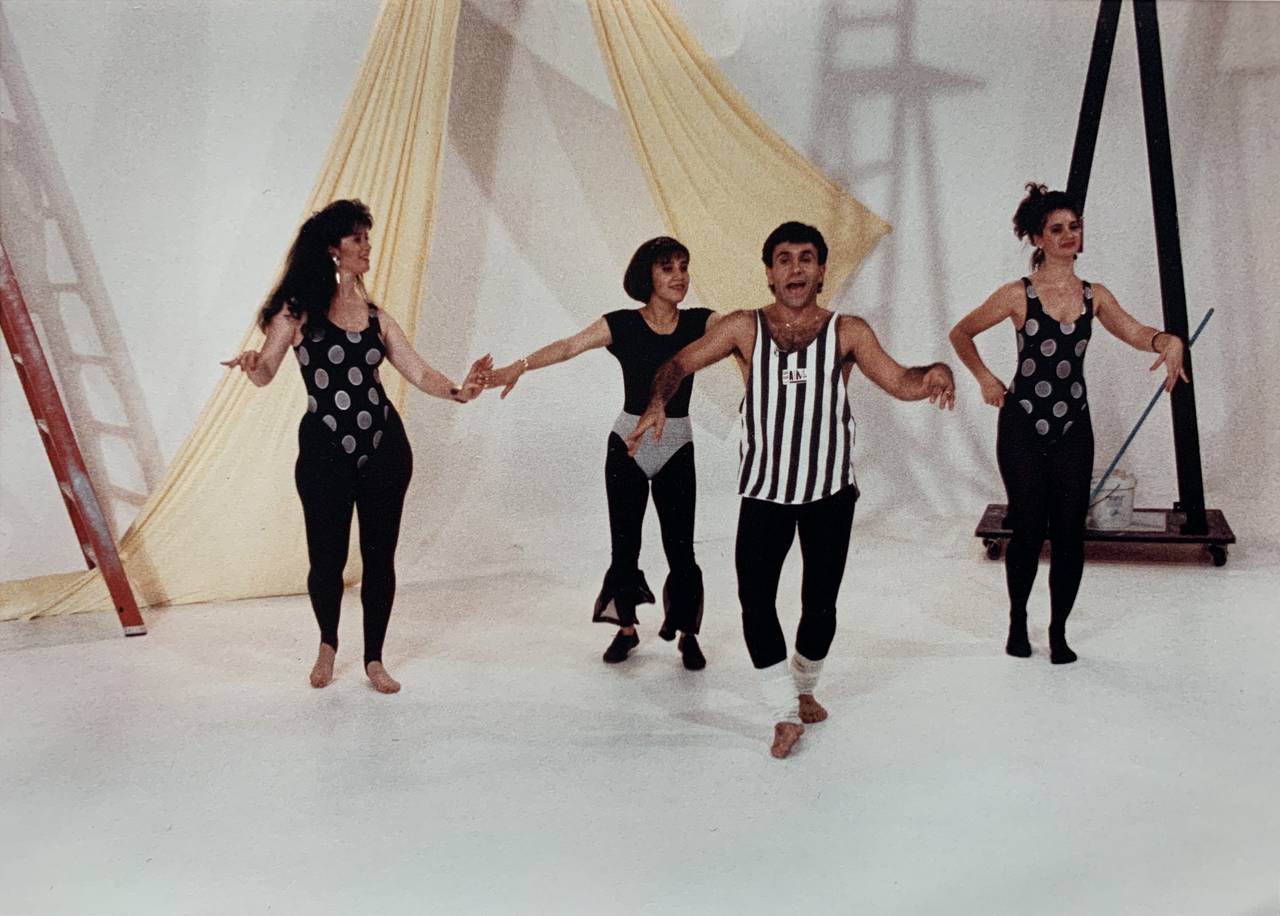

A Revolution in Iranian Dance

After the Iranian Revolution a nationwide dance ban was issued. It was subverted by smuggled video cassettes of dancer-in-exile Mohammad Khordadian,...

How to perform painting

This is perhaps the best way to describe the work of video artist Angel Vergara: Art history meets pop culture, the artist himself appears as a...

About the resistance of our bodies

Hypnotic dances and hybrid beings in cyberspace: Video artist Johanna Bruckner transforms the human body into digital matter.

More than a Honeypot

Young, beautiful and dangerous: the prototype of the Bond Girl still shapes the cliché of spies. Author Chloé Aeberhardt on the reality of espionage...

How to create the unexpected

About life in exile, anarchic art, and the “black milk” of the earth: The art historian Media Farzin met her old friends Ramin and Rokni Haerizadeh...

Why so cryptic?

What lies behind the title of the exhibition by Ramin Haerizadeh, Rokni Haerizadeh and Hesam Rahmanian. And why humor is sometimes the best criticism....

Schirn Preview: Ramin Haerizadeh, Rokni Haerizadeh and Hesam Rahmanian

Exuberant, funny, eccentric and full of allusions: The Schirn presents the Iranian artist collective's first solo exhibition in Germany.

The Future of Video Art

Six international video artists present their new works. An exchange about new trends and forms of expression in film.