From August 23 onwards, a unique project by artist Neïl Beloufa will transform the SCHIRN into a stage. Palais de Tokyo is currently hosting Beloufa's show “L’Ennemi de mon ennemi”, ending May 13. Curator Matthias Ulrich was already there.

The Palais de Tokyo in Paris is currently home to Neïl Beloufa’s overwhelming exhibition project “The enemy of my enemy” (in the French original: “L’Ennemi de mon ennemi”), in terms of both scale and substance. Here, all or almost all the crisis flashpoints in our media-delineated world parade. The supporters and their enemies are spread across the large hall like chess figures on a board and robots are constantly assigning them new positions, in this way and in line with some impenetrable algorithm, creating ever new constellations.

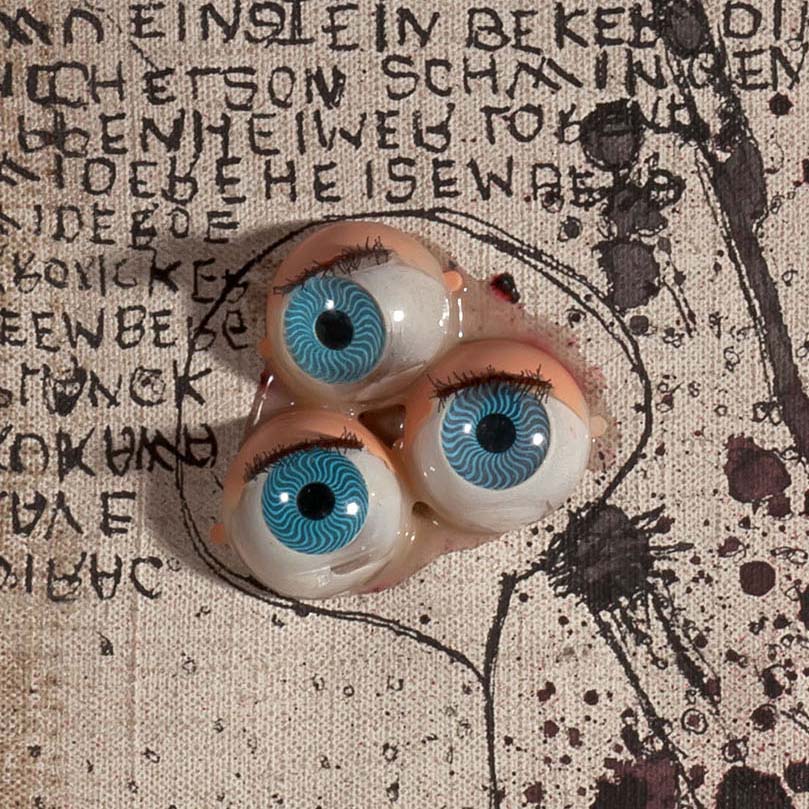

The robots are called either Marat or Sade, so named because video artist Hito Steyerl assigned them these two identities: Jean Paul Marat and Marquis de Sade. In the guise of these two protagonists Steyerl, or rather Beloufa, places violence center stage and also enquires as to their political or rather social legitimation. Alongside these automated pieces (placed on about 100 plateaus) – each of them a miniature stage with inter-communicating artefacts, posters, drawings and paintings, found objects, bric-à-brac, assemblages and all manner of other things – there hang, lie, or stand innumerable other exhibits that provide a set frame like fixed stars in a Milky Way.

How to unlearn knowledge

The psychedelic spectacle into which the exhibition objects are inserted and in which they adopt or insist on a constantly changing angle from which they be viewed, constitutes a set of instructions for how we can unlearn academic knowledge or insights gained in everyday life. For centuries this knowledge has bubbled away and flourished beneath the surface, and desperately lashes out as if seeking to put a final end to all the fun.

Exhibits that provide a set frame like fixed stars in a Milky Way.

The exhibition “L’Ennemi de mon ennemi” is a universal battle, a phantasy of Samuel Huntington’s Clash of Civilizations couched in images, taking place in art and in the sphere of language preserved in art. It is a voiceless and poetic picture book of the political after the end of politics. There will be no victors at the end of this battle, there will be no triumphant new beginning, and certainly not in art, which has learned so perfectly to live and live well in a bubble, transforming images of the enemy into forms of capital.

Which images can we trust?

This exhibition is also provocative with a brilliance that can give you a headache. At the symbolic level it explains the death of the image. And of course does so with an assertion made with images that repeatedly confront you with possibly the most nonsensical question as to which images you can or cannot trust. In so doing, it goes straight to the heart of the image with which the former consensus of a community evolved into constant suspicion, blunting images by degrading them into mere information.

Today, this is to be encountered in almost all exhibitions, a few centimeters to one side of the artwork, where a block of text hangs that tries to capture in words what is to be seen in the piece. Trusting yourself and your own perception has long since ceased to be a matter of course. Beloufa’s exhibition integrates the glut of information and has it slosh back and forth as if in an agitated basin.

An agitated basin full of information

In the middle of it all: static agents, for example two drawings of Picasso, with his leanings toward Communism, both dripping in irony for the addressee opposite, Josef Stalin. Or a baseball, signed by Tony Blair. Or the painting “Le chasseur allemande” by Gustave Courbet, who during a stay in Frankfurt/Main in 1858-9 discovered his passion for hunting. Or the model of an Algerian war memorial dating from 1928, which 50 years later an artist framed in concrete to transform it into a peace memorial. For their part, all these immobile agents represent idiosyncratic movements that only through movement, only by refusing to stand still, can go beyond what can be explained by delimitation.

The beginning and the end of the extended exhibition are marked by an installation by Beloufa with caterpillar-like machines scattered around the space and a scenographic unit, decked out with transparent, movable walls reminiscent of Duchamp or El Lissitzky. On monitors and on the opposite wall you witness a projection of Beloufa’s 2011 video “People’s Passion, Lifestyle, Beautiful Wine, Gigantic Glass Towers, All Surrounded By Water.” Here, success and freedom circumscribe radiant summery neighborhoods accompanied by birds’ chirping, whereby the off-screen voices reel off the positivity of this Occidental utopia eloquently and unquestioningly, as if advertising real estate.

ABOUT TIME. With Marie-Theres Deutsch

Marie-Theres Deutsch was born in 1955 in Trier at the central western tip of Germany, into a family of five women and a father who was an architect....

These boots are made for walking

Shoes are silent storytellers, revealing secrets about their wearer's personality, status and desires. No wonder, then, that artists like Carol Rama...

Seeing nature anew – through a cube

In his early work, HANS HAACKE addressed the relationship between art and nature as well as the social interest in the reciprocal relationship between...

What a festive spread!

Are artists especially creative when it comes to cooking? A glance behind the scenes of art-world kitchens. With the focus this time on festive meals...

Lifting the veil

In the coming DOUBLE FEATURE, Saodat Ismailova refocuses attention on the fate of Uzbek women who, by unveiling themselves, fell victim to femicide.

The film to the exhibition: Hans Haacke. Retrospective

A legend of institutional critique, an advocate of democracy, and an artist’s artist: The film accompanying the major retrospective at the SCHIRN...

A new look at the artist – “L’altra metà dell’avanguardia 1910–1940”

With “L’altra metà dell’avanguardia 1910–1940”, in 1980 Lea Vergine curated an exhibition at the Palazzo Reale in Milan that was one of the first...

Mining nature and humans to death

In the forthcoming DOUBLE FEATURE Florencia Levy offers insights into a dystopian world that is in fact our current world. Starting with a residency...

Non-human living sculptures by Hans Haacke and Pierre Huyghe

In his early work, HANS HAACKE already integrated animals and plants as co-actors into his art. In that way he not only laid the foundations for a...

CURATOR TALK. CAROL RAMA

SCHIRN curator Martina Weinhart talks to Christina Mundici, director of the Carol Rama Archive in Turin, editor of the first Catalogue Raisonné and...

Freedom costs peanuts

HANS HAACKE responded immediately in 1990 to the fall of the Berlin Wall and turned a watchtower into art.

The film to the exhibition: CAROL RAMA. A REBEL OF MODERNITY

Radical, inventive, modern: The film accompanying the major retrospective at the SCHIRN provides insights into CAROL RAMA's work.

The Season of the Witch

In our next DOUBLE FEATURE, artist Margaret Haines will present her video work “On Air: Purity, Corruption & Pollution” (2024). Drawing on the life of...

Now at the SCHIRN: Hans Haacke. Retrospective

A legend of institutional critique, an advocate of democracy, and an artist’s artist: the SCHIRN presents the groundbreaking work of the compelling...

Carol Rama’s Studio: A nucleus of creativity

CAROL RAMA determinedly forged her own path through the art world. Her spectacularly staged studio in Turin was opened to the public only a few years...

PANEL: POLITICAL ACTIVISM BY SELMA SELMAN

Hosted by Arnisa Zeqo, Amila Ramović and Zippora Elders speak with the artist Selma Selman about her artistic career, the exhibition SELMA SELMAN....

Now at the SCHIRN: Carol Rama. A rebel of Modernity

Radical, inventive, modern: the SCHIRN is presenting a major survey exhibition of CAROL RAMA’s work for the first time in Germany.

From studio to dining table: Art with a chef' hat

Are artists especially creative when it comes to cooking? A glance in the kitchens of the art world. This time with a short chronicle of artists’...

Carol Rama in 10 (F)Acts

CAROL RAMA was one of the most provocative female artists of the 20th century. With her explicit depictions of sexuality, physicality, and tabooed...

A lab for art in the public realm

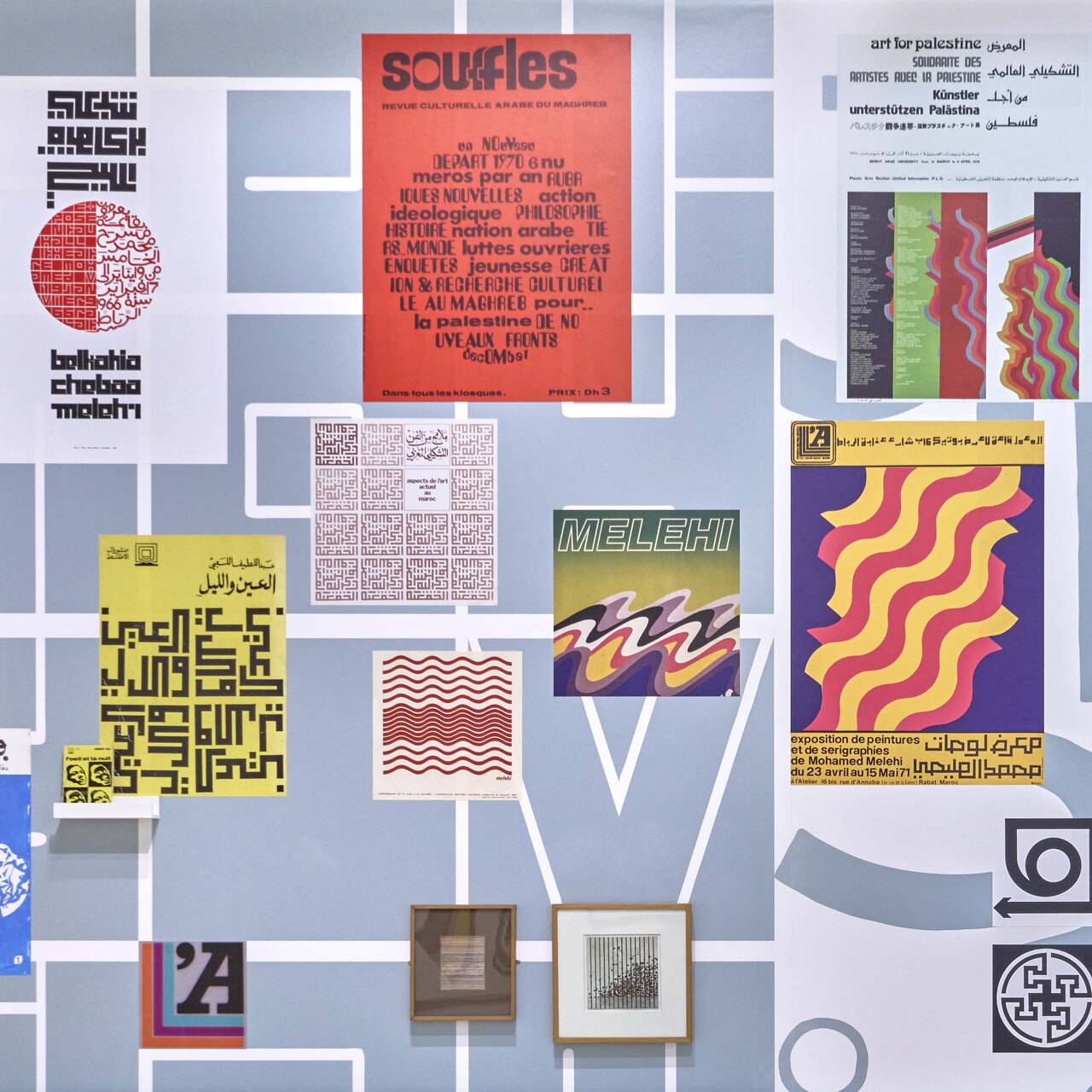

The CASABLANCA ART SCHOOL wanted to make art part of urban life, visible for all, and interacting with the everyday culture of the city. To this day,...

the lived experience of horror

The next DOUBLE FEATURE will host the artist collective Open Group. In their video work “Repeat after Me II”, they examine the extent of the Russian...

Art and the world of journals in the Arab 20th century

Many of the teaching staff at the Casablanca Art School contributed to the journal “Souffles”, an extraordinary example for the strong...

A question of listening

Selma Selman creates her poetry of the future from multiple generations of Roma heritage completed with her subjective family story and history from...

5 questions for Salma Lahlou

Salma Lahlou is an independent curator. Her exhibitions and research projects continuously engage with the CASABLANCA ART SCHOOL. We spoke with her...

ABOUT TIME. With Alfred Ullrich

The artist Alfred Ullrich has spent a sufficient number of decades in the art world and engaging with it to know that attributions can always change....

CURATORIAL TALK: CASABLANCA ART SCHOOL

The curators, Madeleine de Colnet and Morad Montazami, talk to SCHIRN curator Esther Schlicht and filmmaker Mujah Maraini-Melehi about the background...

Casablanca’s Art School and the Bauhaus heritage

The CASABLANCA ART SCHOOL revolutionized the Moroccan art scene and managed to liberate itself from its French colonial past. In some respects, it...

The film to the exhibition: Casablanca Art School. A POSTCOLONIAL AVANT-GARDE 1962–1987

What artists and teachers were the driving force behind the CASABLANCA ART SCHOOL? And what was so special about that new art movement? The film...

The World’s Superfluous Elements

Selma Selman’s art often revolves around recycling, something that places her in a long lineage of artistic transformations

Hidden perspectives on the city (history) of Casablanca

The video series “School of Walking” by Bik van der Pol shows Casablanca from the perspective of contemporary artists and cultural producers - and...

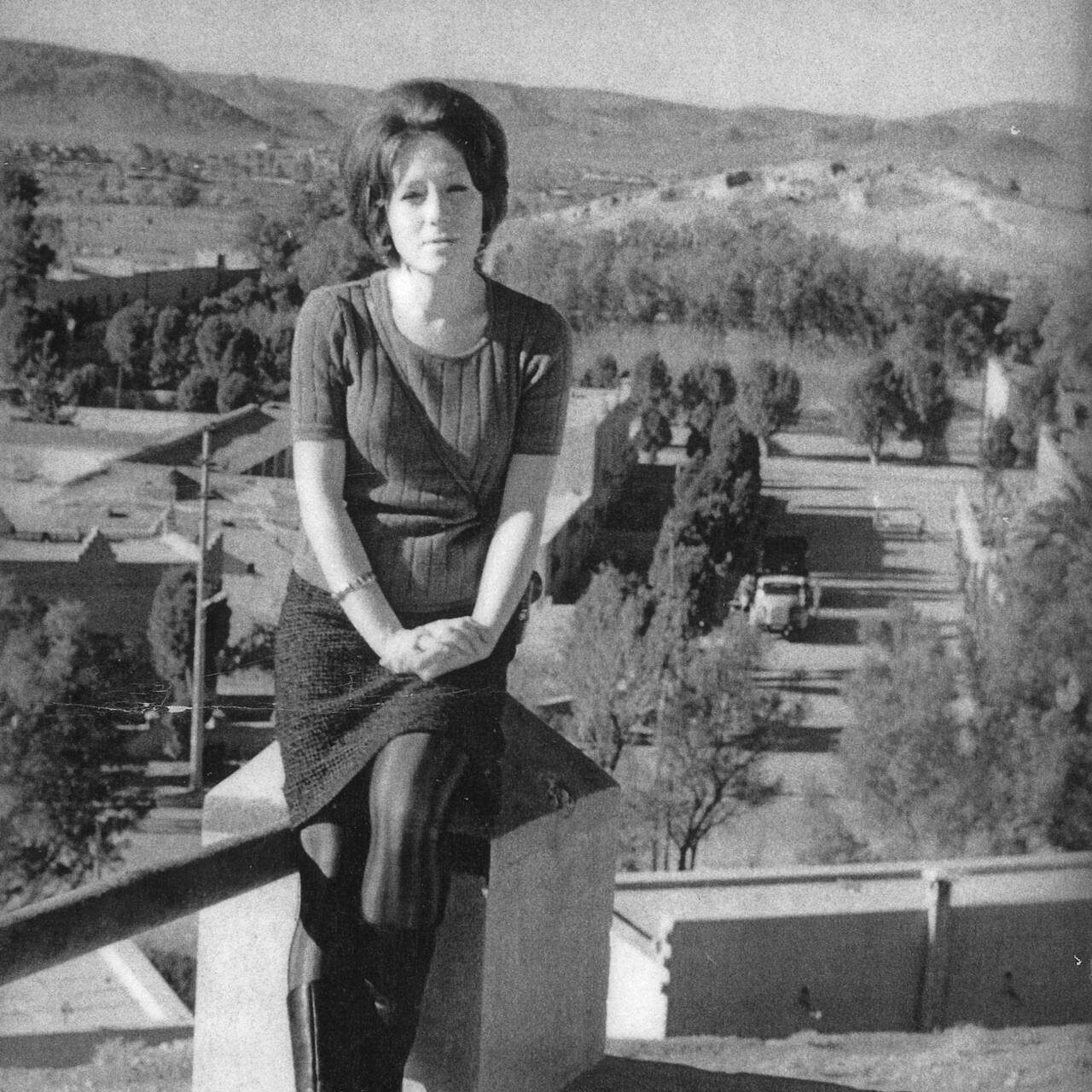

5 questions for Toni Maraini

Toni Maraini arrived at the CASABLANCA ART SCHOOL in 1964 and created the first art history program on Moroccan art from the prehistoric past to the...

ABOUT TIME. With Michaela Dudley

Language is the key to understanding Michaela Dudley’s approach. A polyglot who is comfortable in multiple languages, the Berliner is decisive in her...

ARTIST TALK. IN CONVERSATION WITH SELMA SELMAN

Selma Selman in conversation with SCHIRN curator Matthias Ulrich about her work and the concept of the exhibition "SELMA SELMAN. FLOWERS OF LIFE".

Outlines of tomorrow’s world – under the sign of capitalism

Be it as a sci-fi utopia in the context of the gig economy or as a documentary discussion of the dystopian notions underpinning the fake micronation...

Baby, you can drive my car

For many years now, the art world has had a (love) relationship with cars, be it as a way of representing speed or critical reflection on consumerism....

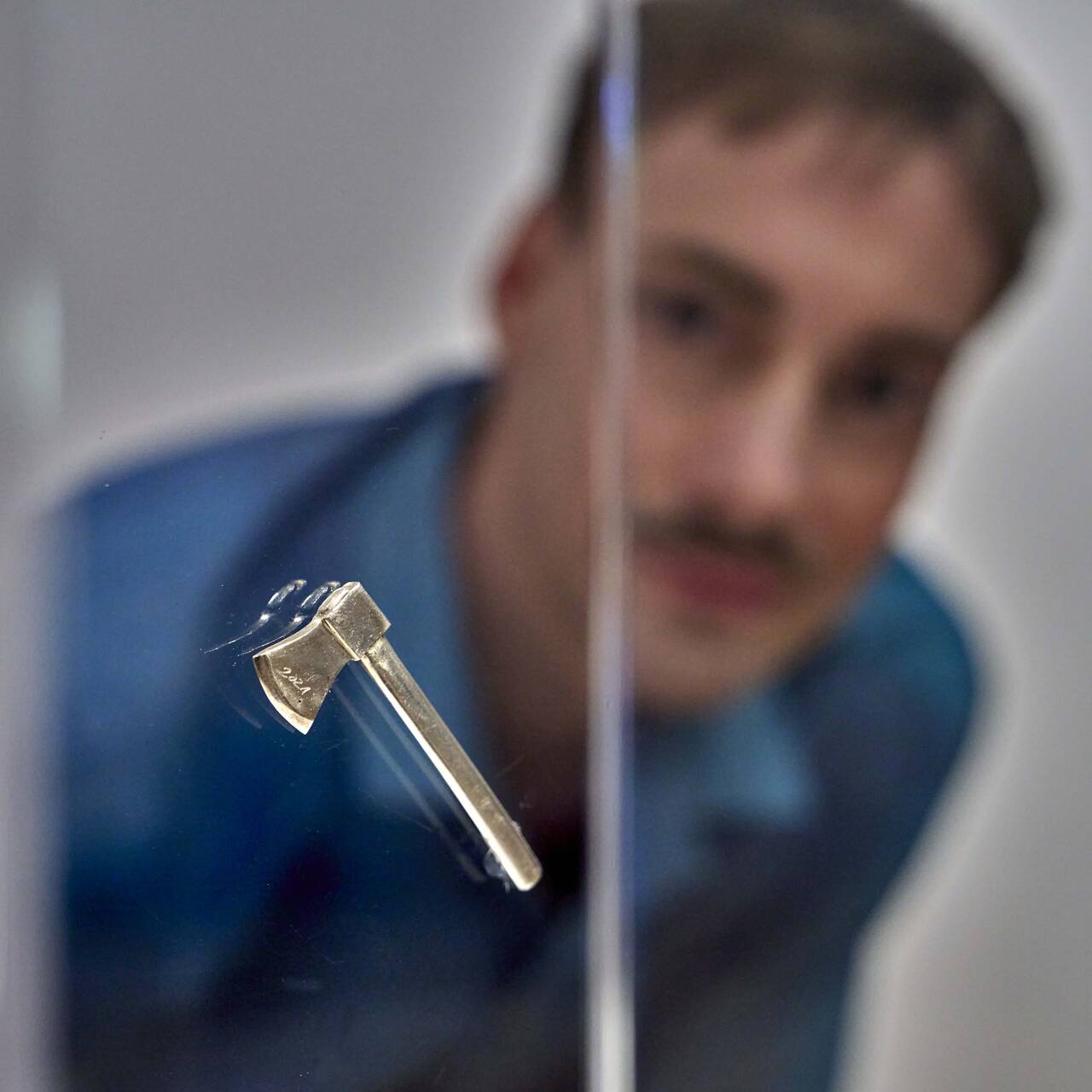

The Call – Städelschule Graduates Show

Until July 21, Städelschule is showing works by its graduating class in an empty office building on Schaumainkai. Various different artistic...

The film to the exhibition: Selma Selman. Flowers of Life

Only a few years ago, she boldly and confidently entered into the spotlight of the international art world. In this video interview, she talks about...

THE STRONGEST KARMIC CONNECTION

The people who surround us in our childhood impact us, regardless of how those relationships make us feel. Often, they make us seek other and new...

Selma Selman and the elastic fabric of the Self

SELMA SELMAN's artistic practice cannot be described as site- or situation-specific; rather, it seems to deal with the self and its constant...

Now at the SCHIRN: CASABLANCA ART SCHOOL. A POSTCOLONIAL AVANT-GARDE 1962–1987

The Moroccan “New Wave”: The SCHIRN presents the influential art scene around the CASABLANCA ART SCHOOL in a first major exhibition in Germany.

FIVE GOOD REASONS TO VIEW SELMA SELMAN IN THE SCHIRN

Poetic, confrontational, surprising: from June 20 to September 15, the SCHIRN presents two new works by the artist SELMA SELMAN in a large solo...

A Sicilian myth in a contemporary guise

What if women can resolve and heal dichotomies? In the coming DOUBLE FEATURE, Elisa Giardina Papa takes the Sicilian myth of the “donne di fora” and...

REVISITING DOUBLE FEATURE: FOCUS ON QUEER ART

Our DOUBLE FEATURE series presents a variety of artists who deal with queerness in their work. We have selected some of the best video interviews for...

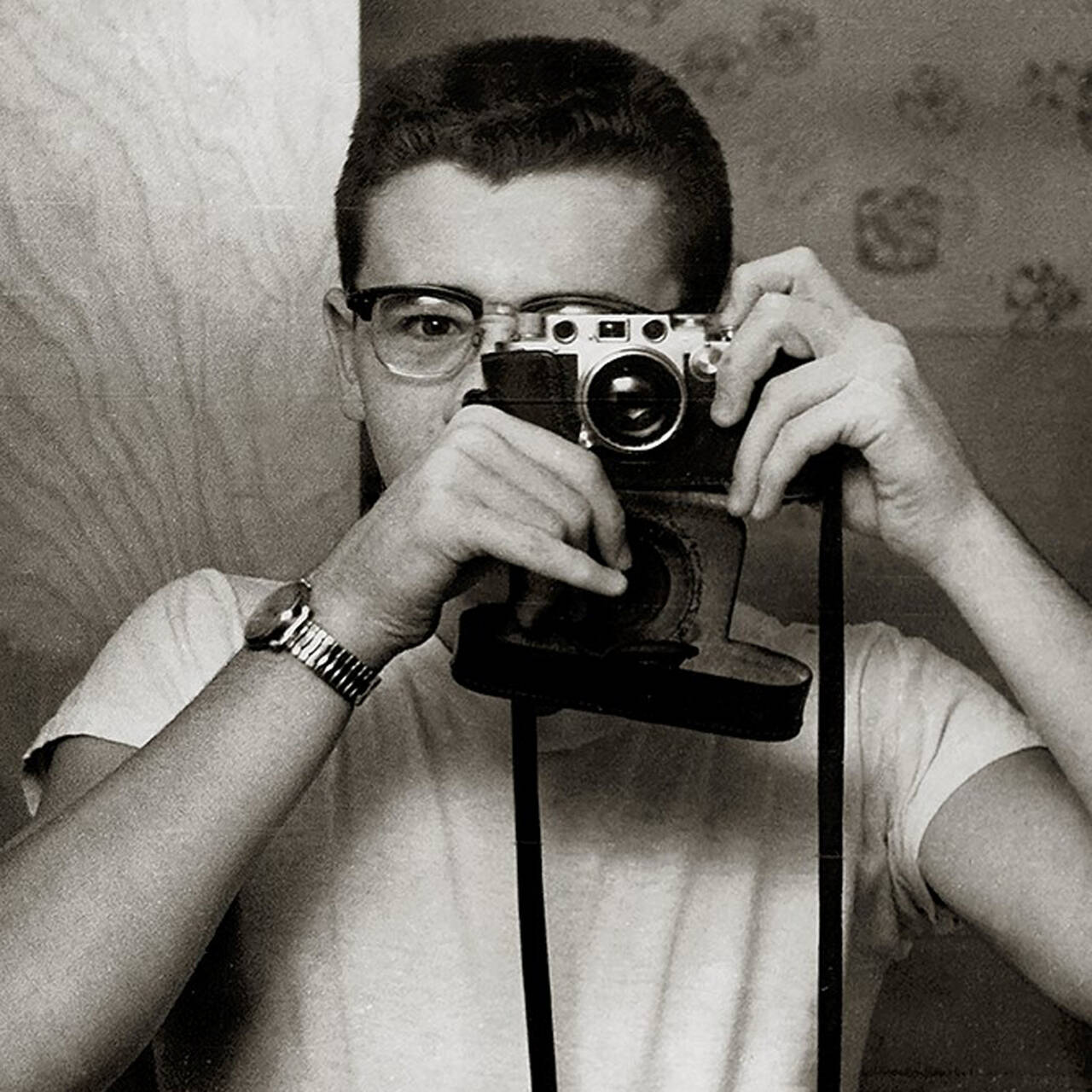

ABOUT TIME. With Abe Frajndlich

Abe Frajndlich can look back proudly on a career of over 50 years as a photographer. In conversation with us he speaks, among other things, about his...

A mix of meditation and leisure

What potential does leisure offer? What happens if nothing happens? In the form of “Untitled (Nothing Happens)” (2023), in the latest DOUBLE FEATURE...

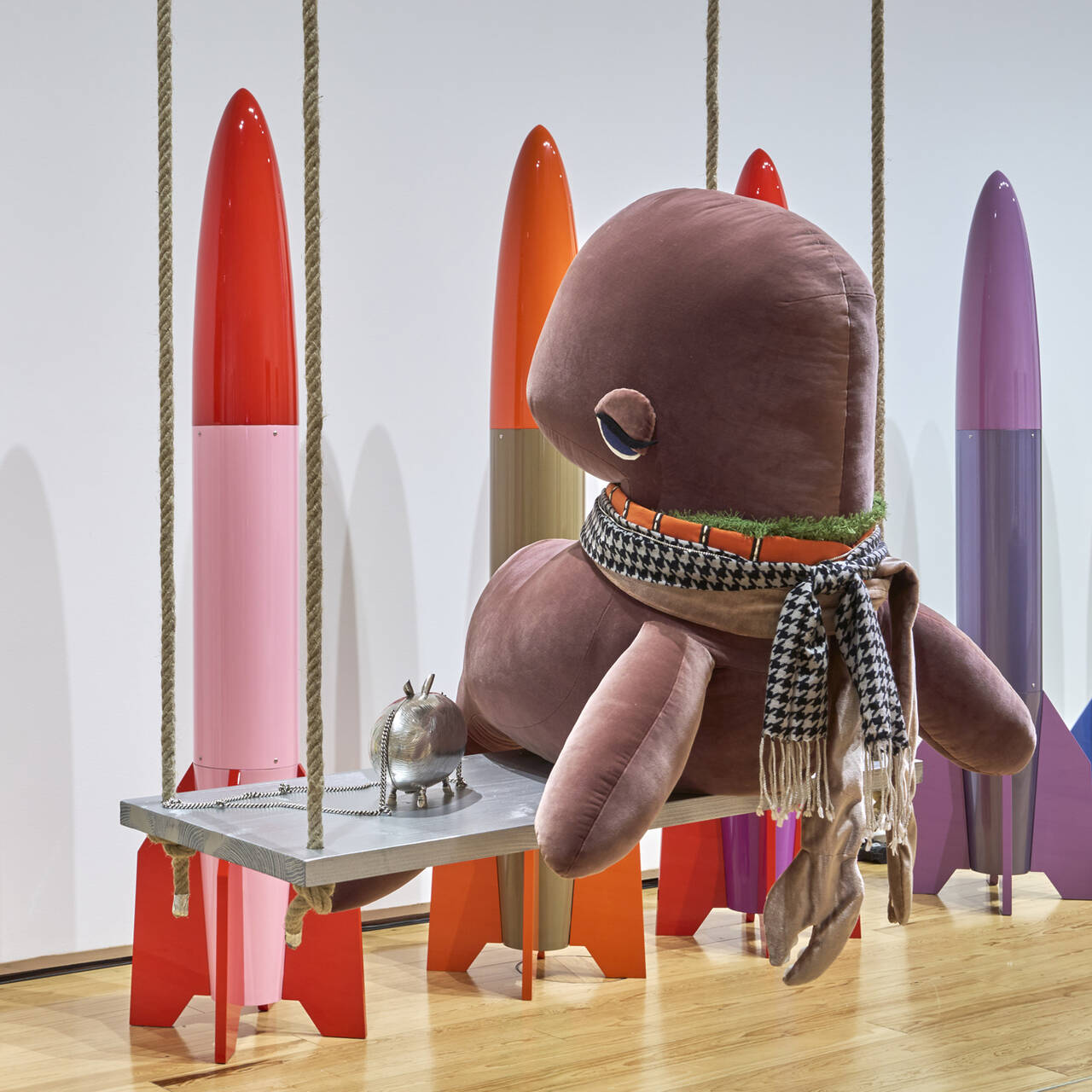

Doing nothing is (not) at the core of the work

Jovana Reisinger reflects on idleness in Cosima von Bonin’s work – is it a sign of luxury, slovenliness, or ultimately a much more meaningful and...

Toxic cuteness

Cuteness overload! Bambi is a recurring reference in COSIMA VON BONIN'S visual world. But such a saccharine appearance can be deceptive. What are the...

From studio to dining table: The (food) culture

Are artists particularly creative when it comes to cooking? We take a look around the kitchens of the art world, this time at the interface between...

Daffy Duck. Here’s to imperfection!

Daffy Duck is an integral part of COSIMA VON BONIN’s artistic oeuvre, but what’s the story behind this polarizing cartoon character?

Where are the hip hop Hotspots in Germany?

Hip hop culture has long since become an integral part of life in German cities. From Frankfurt and Heidelberg through to Bietigheim-Bissingen near...