The Harvard Art Museums host the largest Lyonel Feininger collection in the world. How did that happen and how was the relationship between the artist and the world famous institution? A conversation with directors Lynette Roth and Laura Muir of Harvard Art Museums.

It is unseasonably warm for early December when I rush down the Cambridge sidewalk on my way to meet Lynette Roth and Laura Muir of Harvard Art Museums. I’ve been to the Harvard Art Museums a couple times before but have always used the main entrance on Broadway. To meet Lynette and Laura in the Art Study Center for our conversation about Lyonel Feininger, I was told to use the side entrance left of the loading dock driveway which of course I’m having trouble finding with 5 minutes to spare on the clock.

Architecture made of glass and light

Relief floods me when I spot the large grey shutters at the back of the massive brick building that was once the Fogg Museum and the unassuming glass door next to them that very simply reads: Staff. When entering the foyer, I’m met by a very friendly receptionist that already knows my name, hands me a printout sticker to wear visible on my sweater, and tells me to wait for Jennifer, the public relations manager, to pick me up. As usual in any public building in the US since 2001, my bag is searched, and a handheld scanner makes sure I’m coming in peace. Jennifer appears through the glass doors in front of me and asks me to follow her to the fourth floor. When exiting the elevator, she asks me to store my bag and my jacket – I’m only allowed to bring my phone and my notebook into the study center to preserve the integrity of the art works and the space. We’re even washing our hands thoroughly at the sinks set up in the corridor. When I finally make it into the Art Study Center I’m flashed by the space – metaphorically and literally. Instead of walls the space is surrounded by glass panels, some of them darkened by white shades to avoid direct sunlight onto the artworks displayed on the build-ins that run around the outer glass walls.

In 2014, the three major Harvard art institutions – the Fogg Museum, the Busch-Reisinger Museum, and the Arthur M. Sackler Museum – were united under one, very see through roof, the brainchild of star architect aka “the master of light” Renzo Piano. In combining the old with something fresh and new, Piano added a glass canopy on the top of the massive brick building of the Fogg Museum, creating a covered courtyard in the middle that is now the heart of the museum space and lets visitors sneak a peek of each floor all the way up to the sky. The galleries are organized chronologically with contemporary art on the ground floor working back through time on the second and third floor. The Art Study Center sits right under said angled glass roof, the brains of the Harvard Art Museums reserved for close-up research and art classes for students, scholars, and art industry peers alike.

THE BUSCH-REISINGER MUSEUM: A FOCUS ON GERMAN ART IN THE USA

There are graphite sketches and watercolors, comic strips, ink drawings and wood prints spanning Lyonel Feininger’s work from as early as 1892 way into the 1950s. For the first couple seconds I’m just blown away by the diversity of pieces in the room. I am welcomed by Lynette Roth, the director of the Busch-Reisinger Museum, and Laura Muir, the Director of Academic and Public Programs. Both are super nice, especially after I directly break one of their graphic pens – I’m not allowed to use my own ball-point pen to avoid accidents not surprising with all that amazing artwork so close by.

Alright, let’s get started. I have a couple of questions to get us going and to learn a little bit about the Busch-Reisinger Museum from you, Lynette. What is your focus here? How does the Feininger collection fit into it?

Lynette Roth: “The Busch-Reisinger Museum is unique in the United States because it focuses on the art of German-speaking countries and especially on Germany. It was founded in 1903 as the Germanic Museum and I often think about Feininger’s relationship to the museum: He's a German American artist, who spends pretty much his entire career until he no longer can in Germany and is often only considered in that context. But for me it's that transnational relationship that is the whole reason for the existence of the museum. And because we are a teaching and research institution, we're the ideal place for this kind of archive, and it really is the Feininger archive.”

So, you have students come here to do research?

Lynette Roth: “Oh, yeah. So, we see this (gestures around) in many ways as the heart of the museum. When we opened this building in 2014, the idea was to give a lot of space to what we call the art study room to make the collection accessible for teaching and research, we hold a lot of classes here constantly.”

Laura Muir: “Harvard faculty, as well as other local universities and colleges bring their students here all the time. And it's not just art history students, there are students across disciplines from economics to sociology and more. It's important for us that our collections are seen as a tool for students across the university. There's only a very small fraction of our collection on view in the public galleries, about 2%, but we have vast collections in storage that are only accessible through this space. It's a place where you can take a closer look at art works without glazing in front of them, a kind of slow looking that we really value here at the museums. We also do public programs; we call them arts study center seminars. There was one this morning where they were looking at the backs of paintings at all the stickers and labels that one can use to trace the history of a work of art. I pulled this out (opens a book and starts to flip through pages until she finds an old black and white photograph): This is in the Adolphus Bush Hall, which was one of the earlier homes of the Busch-Reisinger Museum.”

Lynette Roth: “It's a fascinating space because it was built for the then Germanic Museum and still houses our plaster cast collection. The museum actually started as a museum for reproductions rather than original works of art. It was sort of a teaching laboratory: If you couldn't go to Germany to see the originals like cathedrals and churches you could see architectural elements of them in form of plaster casts right here in Cambridge. This picture shows how far back the relationship with the Feiningers goes and how what we do today is already in our DNA.”

Feininger visited Harvard and the Busch-Reisinger Museum regularly starting in the early 1950s when his son T. Lux worked at Harvard and his former colleague Walter Gropius taught at the university.

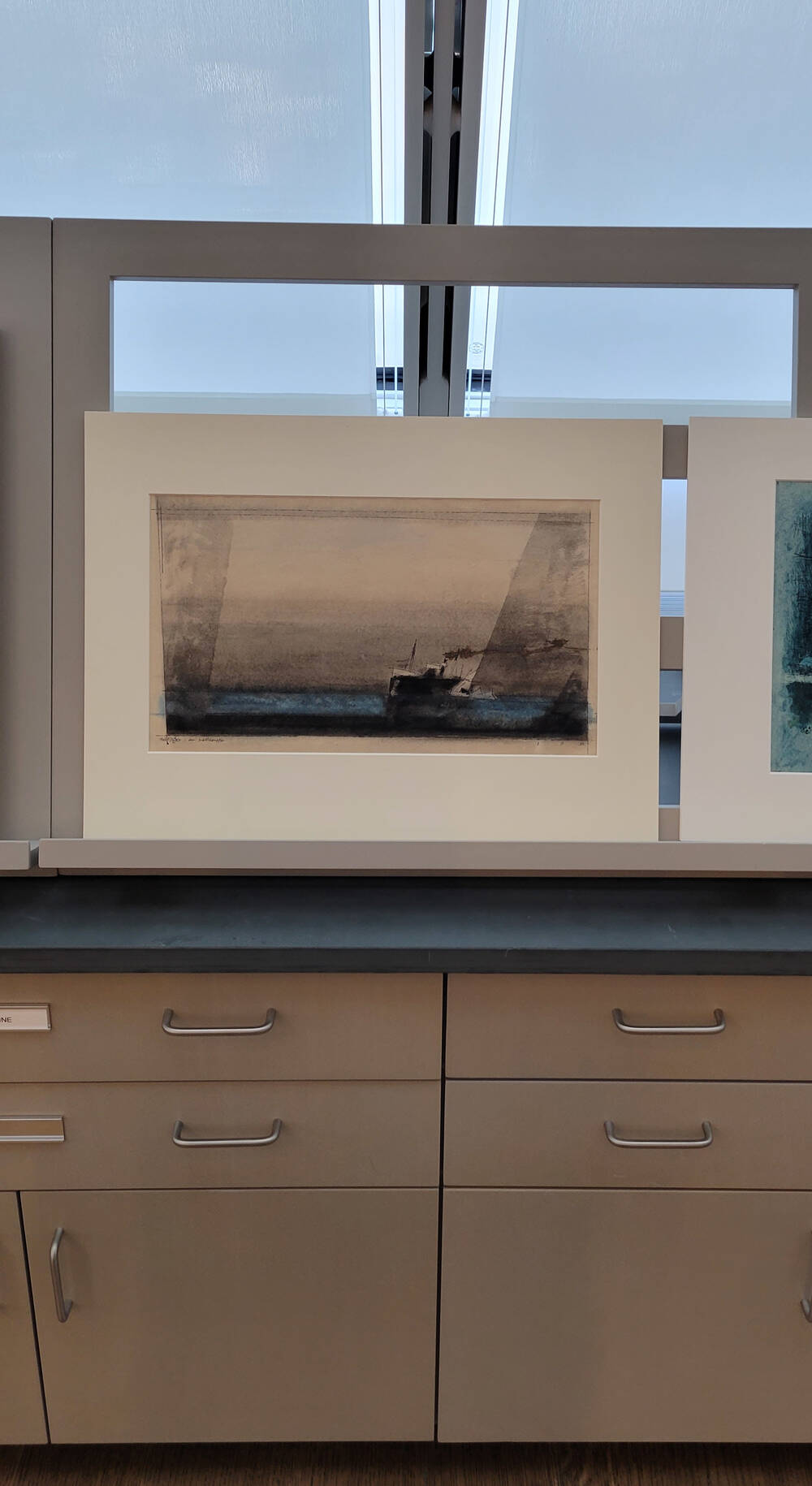

Laura Muir: “As Lynette was saying, the early collection was all reproductions. It was around 1930 when the Busch-Reisinger Museum started collecting originals. Feininger’s work was some of the earliest original works to be collected by the museum. This picture was taken in the 1950s, it's a photograph by Feininger and shows his wife Julia and the curator of the Busch-Reisinger Museum at the time, Charles Kuhn. There are some Bauhaus related objects on the table but also the earliest acquisitions of Lyonel Feininger: illustrations from a ghost story, which unfortunately are at our Somerville site right now, but that beautiful seascape over there the “Freight Steamer” from 1932 (points to one of the watercolors propped up against the outer wall of the study space) was acquired in Berlin by Charles Kuhn as maybe the first original art work of our Feininger collection.”

Lynette Roth: “Charles Kuhn was going to Germany in 1934 and buying works by artists who were already considered degenerated art - they didn't necessarily use the term specifically at the time, but that was the path things were already on in Germany for a while. The entire history of the museum is connected to the history of Germany, the transnational relationship between Germany and the United States, how the cultural and political events affected art and artists alike. I always say this art collection doesn't exist without thinking through those historical events and what happened, not just exiles and emigres after the war, but already before the war. For example, what motivated the focus on modern art the beginning in 1930? That was a very important shift for the museum as well and Feininger is there through it all, well Feininger’s work.”

Laura Muir: “The Feininger family knew early on that Harvard and this curator, Charles Kuhn, were establishing a collection focused on German art. So, when Feininger had to return to the US and he miraculously was able to bring so much of his work back to the United States with him, they were really looking for a place where this could live and where students could learn from it. At the same time Gropius was arriving in the US and connected to Harvard which then started the whole Bauhaus initiative in the US. So, it really made sense to the Feininger family, to Lyonel and after he died to Julia, and especially to their sons to continue to make gifts and really create this research center focused on his work.”

LYONEL FEININGER: RETROSPECTIVE

October 27, 2023 – February 18, 2024