Until July 30, artist Lena Henke is presenting an installation in the SCHIRN Rotunda. We asked her about her links with Frankfurt, her life in New York, and the challenges of walk-on sculpture.

Schirn Mag: In 2010, you were a member of Professor Michael Krebber’s master class at the Städelschule. You then moved to New York. How do you view Frankfurt now, seven years on?

Lena Henke: I actually only came to New York via Frankfurt. As a student of the Städelschule I was always very active and organized small-scale exhibitions in Frankfurt. For example, my fellow students and I created an apartment gallery in which we exhibited smaller works from renowned private collections in Frankfurt, so I had my little network. I ran the press desk at the Portikus and it was there that I was able to meet the exhibiting artists Dan Graham, Trisha Donnelly, Sergej Jensen and Rachel Harrison, who each spent one or two weeks in Frankfurt preparing their shows. I met up with them again when I visited New York on a tourist visa after the Städelschule, and that’s when I had a stroke of luck: Sergej Jensen needed somebody who could sew and to support him in the studio. Hence I spent the first year in New York without a salary, grant or support but somehow made it work. In any case, my time in Frankfurt was unbelievably intense. The Städelschule itself can be hard of course, it’s not for nothing that it’s sometimes known as the “cutthroat Städelschule”, but I benefitted a great deal from being around Michael Krebber. I have fond memories of that time and I’m looking forward to coming back now. I also think now is the right time.

How did you find New York initially? What did you think of the art scene there?

The first year was pretty difficult, but in New York you get to know people really quickly. Everyone is unbelievably considerate. I once heard that this period is called “the blazing first 18 months”. That actually applies to anyone who comes to New York: 18 months of action. You quickly find yourself invited to take part in group shows and you then need to keep up that level of energy. That’s not the case in Frankfurt where things work differently and you first have to prove yourself over a period of three years. In New York things often move much faster.

You are a sculptor in everything you do and produce impressions made of epoxy resin and heavy aluminum cubes, but also walk-on sculptures made of sand, smaller objects made of ceramics and very lightweight plastic boxes. How does your focus shift when you create works for the public space?

I think sculptures belong outdoors. In my opinion, they should always work outside. The openness of an urban space with its systems and structures has always interested me more than a white cube. In 2014, for example, I worked with Marie Karlberg to organize “Under the BQE”, an illegal exhibition with sculptures in the outdoor space under the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway. We wanted to use the city quite literally as the underlying medium, as a “canvas” as a painter might say; for me it works like a huge plinth, like a background against which you can judge whether the sculpture still works or not. How does it appear on the ground? How do observers perceive its weight or dimensions? What happens when you walk around it? With my new production for the SCHIRN, I had to ask questions like this quite specifically, because the Rotunda is a sensitive urban space, both anteroom to the art gallery and at the same time the sole, heavily frequented connection between the lively Römer Platz and the Dom. The “ambiguity” of this space: not inside and not outside, not public and not private, puts particular demands on my work.

How do you respond to this public character? Is that a conflict?

No, I thought about the “monads”, so to speak, at great length, the smallest details. “You have to zoom into the small scale, your own body, AND into the big scale, society, to realize that each contains the other. The actual state is noted in the detail”, Thomas Bayrle once said. People are monads. The Rotunda is the brain, or the egg-timer; like a painting by Hieronymus Bosch, the people swirl through it. It’s only now, with Frankfurt’s Old Town being reconstructed, that the Rotunda has become a thoroughfare. Everything is very tight, very boxed in, and works as if it were on a street – as if it were on a pavement. I aim to block this passage, to link the inside with the outside and thus to bring the greater whole into play. The Rotunda thus becomes the head of the SCHIRN that the visitors enter and change. The cylinder can likewise be considered a walk-in sculpture in which the pillars represent the skeleton of the body, as it were. I placed two aluminum sculptures in the shape of eyes in the entrance area, which are filled with sand from the top, from the walk-round concourse. The eye as the human organ of sight and recognition appears in two different forms, and the pupils are also different sizes, as if they were looking at different things or reacting to the light streaming in from the glass roof above. Yet the sand robs them of their sight and possibly the visitors in the Rotunda also get a little sand in their eyes or end up taking a bit of sand back home with them in their jackets or on their shoes …

Does this work also reflect your interest in artistic sculpture parks in which the private sphere and nature become one?

Yes, exactly. I think it’s great to have visitors walking directly on and through my sculptures, to get them moving – really as if they were walking through a sculpture garden. A few years ago, I started to examine sculpture parks more closely and, more precisely, those places that somebody has already developed, in order to own a garden, a home that aligns precisely with their preconceptions and to realize that dream. I began my research journey in Oslo, where the sculptor Gustav Vigeland created his own sculpture park. I subsequently travelled to Rome to see “The Garden of Monsters”, which Pier Francesco Orsini had created for Giulia Farnese, his already deceased wife, in the sixteenth century. What I found so interesting there was that after all those centuries the forest had reconquered the park. There was a similar situation in Mexico City in the “Las Pozas” park created by Sir Edward James, who began to build quite a number of sculptures, then stopped and left them half-finished so that plants and nature could occupy them. There, for example, you find cement pillars with palm leaves growing out of them, and the difference between nature and sculpture suddenly disappears. The idea in the SCHIRN is for people to walk over the sand, over my material, to get it moving, to make it trickle out of the windows into the sculptures and to leave their own footprints behind.

Conventional sand – beige and coarse – has been a central theme of your work for quite some time. Recently you created a breast made of sand for “Ascent of a Woman” for New York’s High Line plinth, a work which has to be continually remolded. What is the significance of sand as a material for you?

For me, sand is material and production. Sand is closely related to the history of bronze casting, because sand is required to produce bronze. I work not with bronze, but with sand, which itself is sculpture for me.

As in your exhibition “Available Light” (2017) at the Kunstverein Braunschweig, light also plays a key role at the SCHIRN Rotunda. What inspired you in this regard?

Light in combination with the colors pink, blue and yellow is a source of inspiration for the architect Luis Barragán, whose house I visited in Mexico City. But I was also influenced by Mathias Goeritz, an artist and architect, who emigrated from Germany in 1941 and then lived in Mexico City. Barragán worked very intensely with indirect, natural light, and in the SCHIRN Rotunda too I integrate the light that falls through the glass dome onto the installation. In any case, it is loud.

5 questions for Salma Lahlou

Salma Lahlou is an independent curator. Her exhibitions and research projects continuously engage with the CASABLANCA ART SCHOOL. We spoke with her...

ABOUT TIME. With Alfred Ullrich

The artist Alfred Ullrich has spent a sufficient number of decades in the art world and engaging with it to know that attributions can always change....

5 questions for Toni Maraini

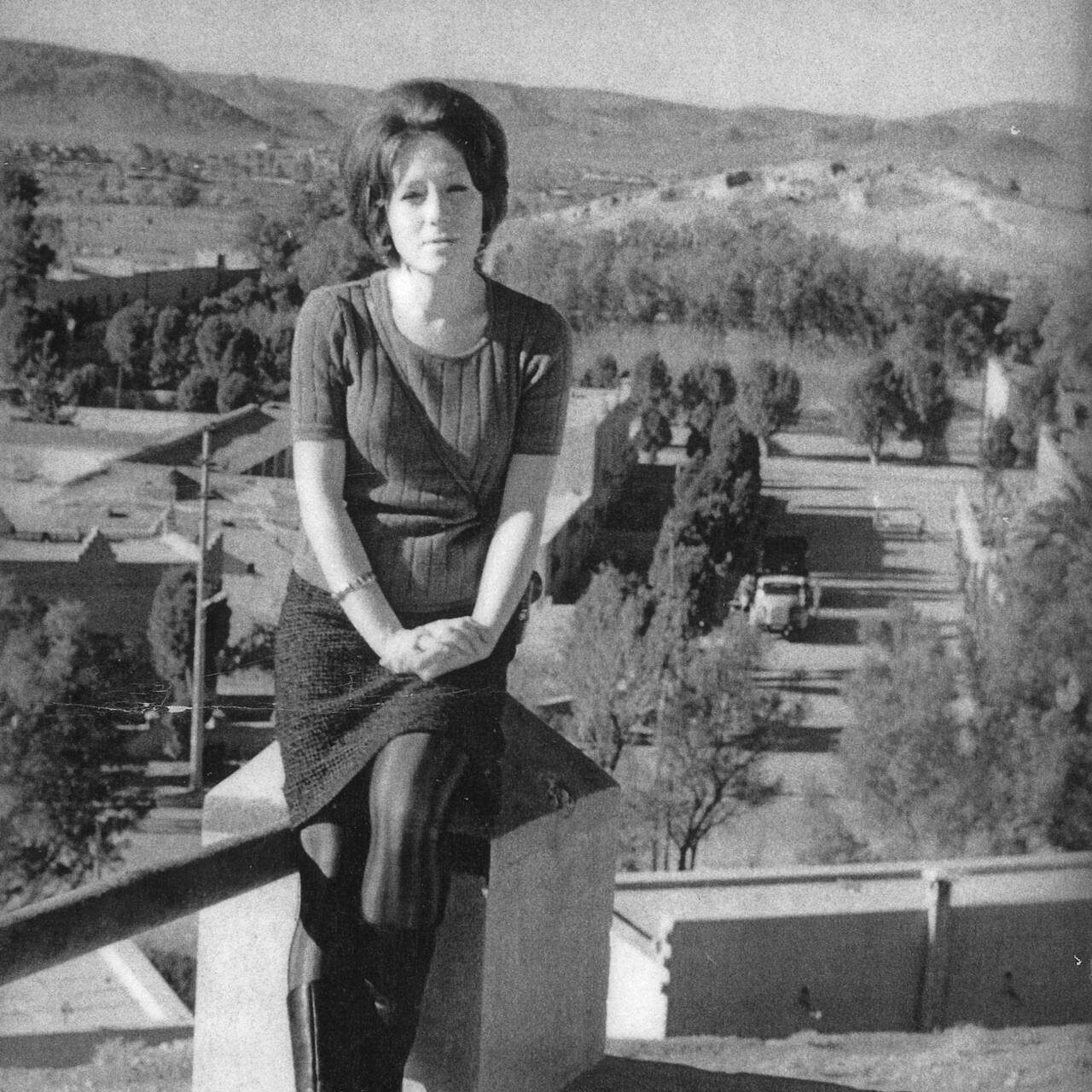

Toni Maraini arrived at the CASABLANCA ART SCHOOL in 1964 and created the first art history program on Moroccan art from the prehistoric past to the...

ABOUT TIME. With Michaela Dudley

Language is the key to understanding Michaela Dudley’s approach. A polyglot who is comfortable in multiple languages, the Berliner is decisive in her...

ABOUT TIME. With Abe Frajndlich

Abe Frajndlich can look back proudly on a career of over 50 years as a photographer. In conversation with us he speaks, among other things, about his...

5 questions for Mary Messhausen and proddy produzentin

With the performance "Thonk piece: Hungry for Stains", drag queens Mary Messhausen and proddy produzentin will open the exhibition COSIMA VON BONIN....

Lyonel Feininger and the Harvard Art Museums. Part 2

The Harvard Art Museums host the largest Lyonel Feininger collection in the world. The directors Lynette Roth and Laura Muir chat about Feininger’s...

Lyonel Feininger and the Harvard Art Museums. Part 1

The Harvard Art Museums host the largest Lyonel Feininger collection in the world. How did that happen and how was the relationship between the artist...

Empathy, but how? Julia Grosse talks to Elisabeth Wellershaus

What role do empathy and emotions play in the cultural world of today and tomorrow? In the first part of the interview series, curator Julia Grosse...

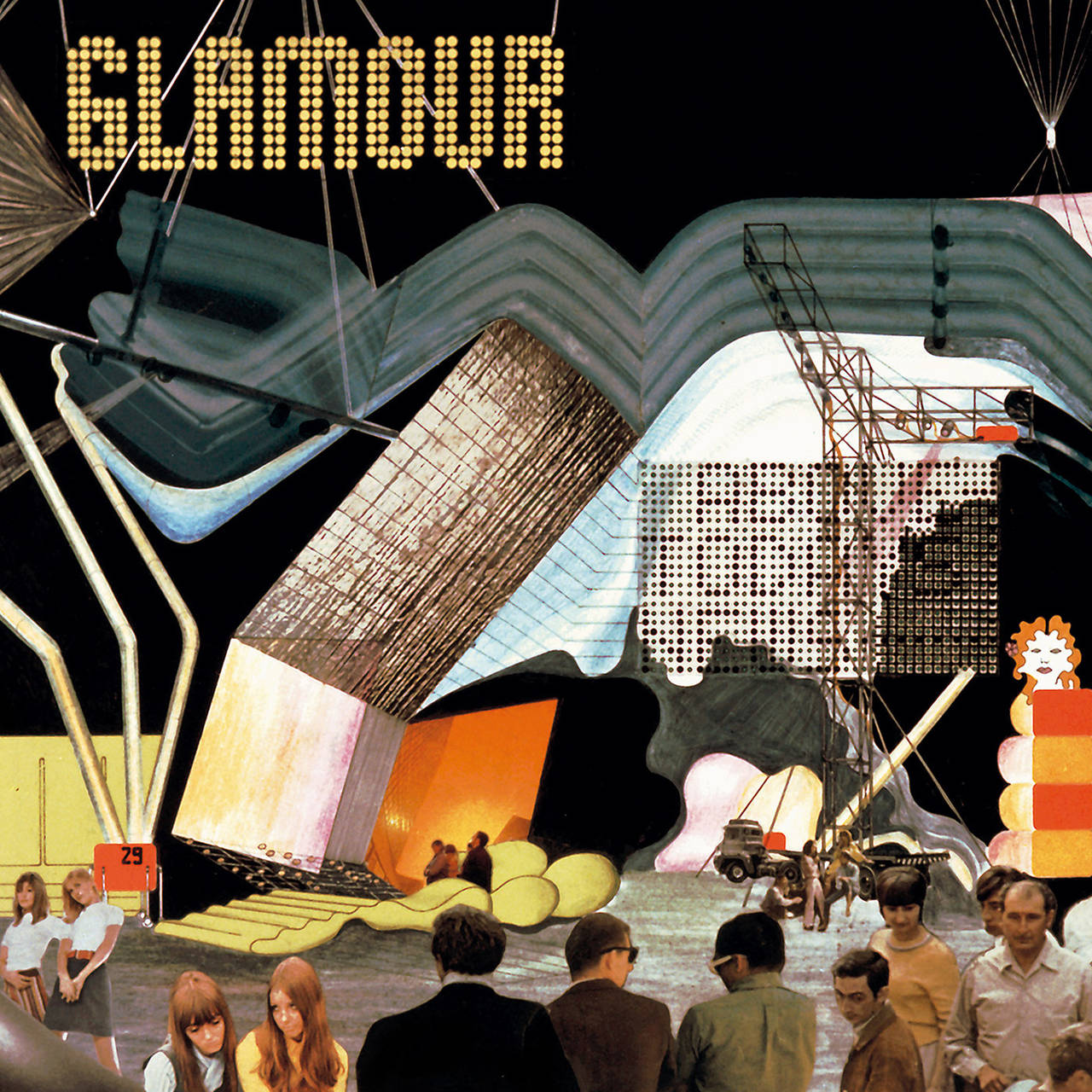

The eventful history of plastic in design

The collection of the Design Museum Brussels consists entirely of objects made of plastic. No wonder, that some of the works in PLASTIC WORLD, which...