In his early work, HANS HAACKE addressed the relationship between art and nature as well as the social interest in the reciprocal relationship between creatures and their environment. These issues are as topical as ever. Many artists continue to focus on the relationship between art and nature, or are doing so all the more given the escalating climate crisis, and one of these is Amy Balkin.

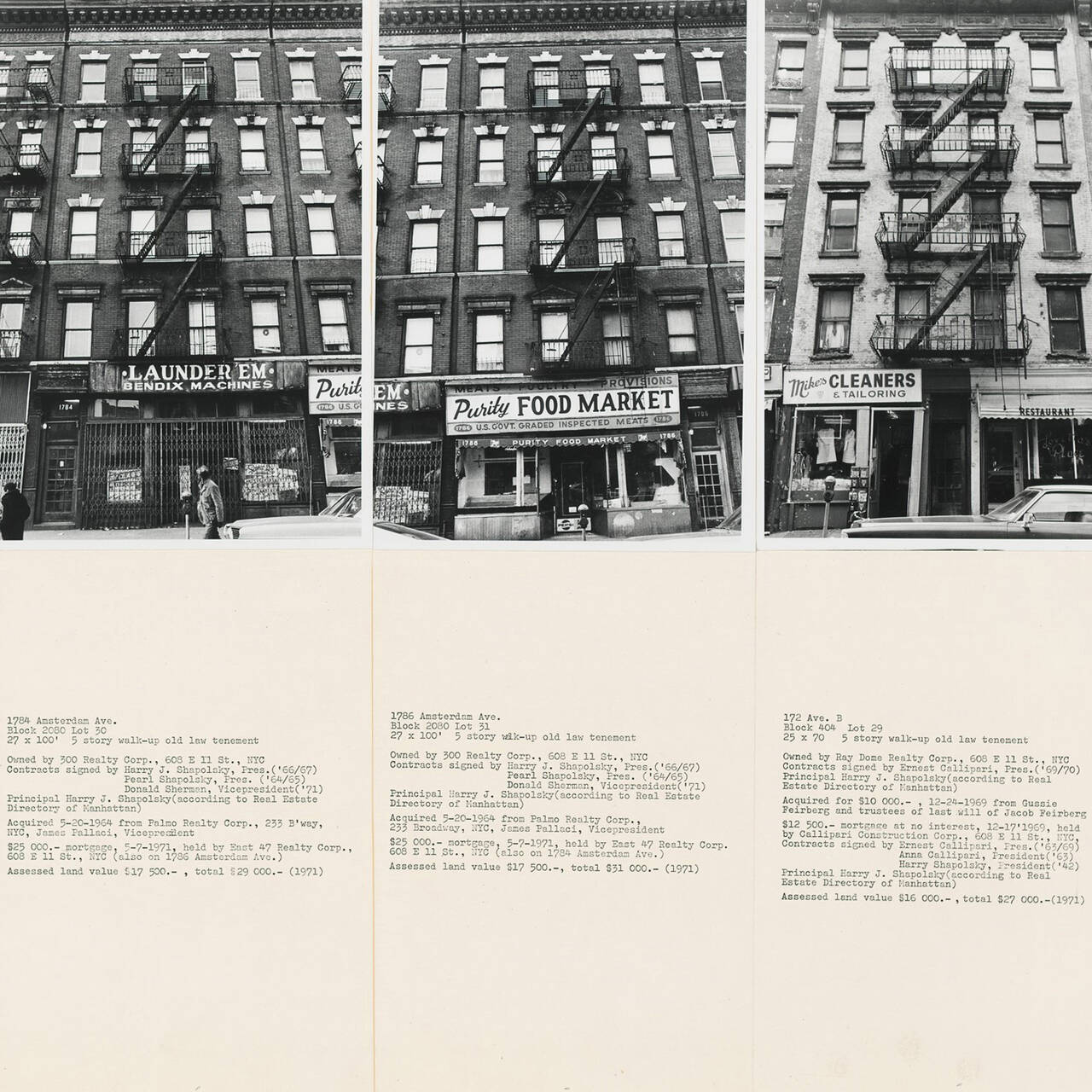

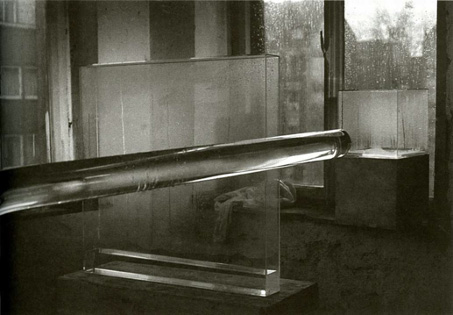

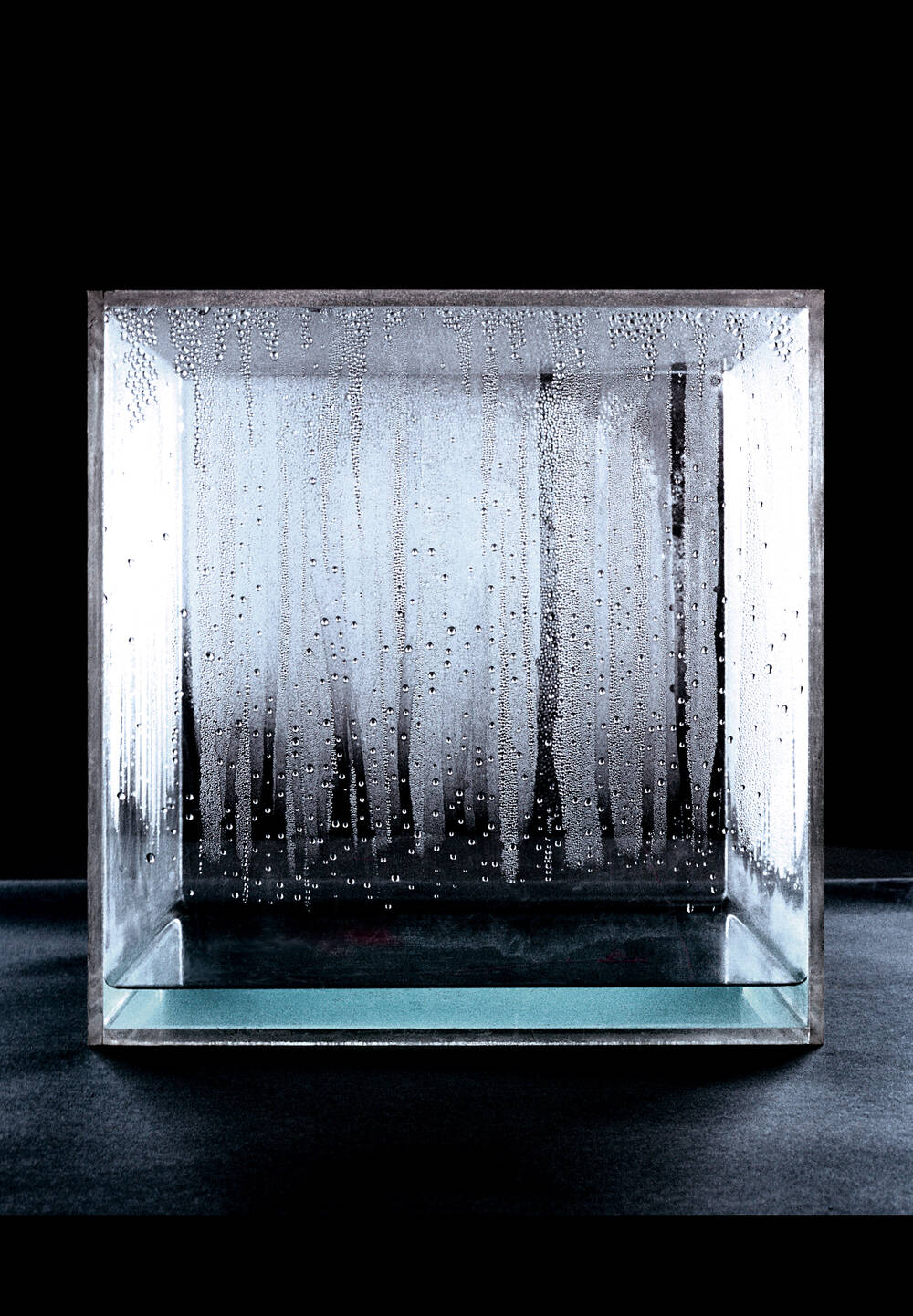

A photo taken in Hans Haacke’s Cologne studio in 1965 shows the diversity of shapes he created at the time by combining Perspex and water. On view are a total of three works: the “Large Spirit Level” (1964–5) hanging in the space, and two “Condensation Cubes”. Haacke started building such cubes in 1963 in various different versions. The version with identical sides and entitled “Condensation Cube” is currently on display in the retrospective at the SCHIRN and is probably the best known. He made it in two sizes, and there is also a far taller “Condensation Wall” and a flattish rectangular “Condensation Floor”.

What they all have in common is that they enclose a small volume of water and thus, in their interior, trigger the infinite cycle of condensation and re-condensation. On each side of the box the condensation causes a filigree veil of droplets, a poetic performance presented on a transparent proscenium stage.

A cube in the museum

From the very beginning, it was key to Haacke to grasp biological, physical, and social systems as equals and emphasize how they are interwoven. In terms of its composition, the photo from the studio pinpoints nothing less than this artistic approach: The cylinder of the “Large Spirit Level” combines the tall cube with the equilateral cube visually, where the image takes the window as its vanishing point. Moreover, Haacke consciously chose a rainy day to take the photo in order to create an analogy in the image between the drops on the windowpane and those on the transparent Perspex surfaces. With this visual referencing of interior and exterior, of the space of nature and that of art, Haacke makes it clear that what takes place inside his artworks is a natural process identical to that which plays its part in the global climate.

The “Condensation Cube” is, however, clearly designed for use in an interior: Through their physical presence, each person directly influences the speed of the condensation process, as for that matter does the heat of the sun or from central heating.

With the choice of a radically simplified, rigid shape (the cube), which he then confronts with the processual character of the water, almost in passing Haacke comments on the US Minimal Art movement that was making such a splash at the time. The latter’s exclusive use of stereometric basic bodies generated a completely new concept of sculpture. Here, too, often plastics that visually resembled glass were used, as their transparency and/or reflective properties explored issues of perception and space. How do the viewers relate to the cubes in the space that purportedly possess no qualities whatsoever?

With his condensation cubes, Haacke was likewise interested in the viewer’s physical relationship to the work, but not only as regards the real surrounding space; rather, what he had in mind was an expanded artistic and social context. This can be seen from the influence that the audience quite manifestly has on the condensation. Haacke does not intend for our presence, our actions, and our gaze to simply bounce off the smooth surface finish, as was the case with minimalist sculptures. Instead, any person who looks through the cube can become aware of the role they play in our society with regard to the climate process.

Haacke’s early works are part of those art currents in the 1960s and 1970s that explore the relationship between art and nature and reflect the growing social interest in the interrelationships between creatures and the environment, along with the new insight that this relationship is out of kilter. These issues are as topical as ever, and many contemporary artists continue to focus on the relationship between art and nature, indeed this emphasis has intensified specifically in light of the escalating climate crisis.

A cube in the air

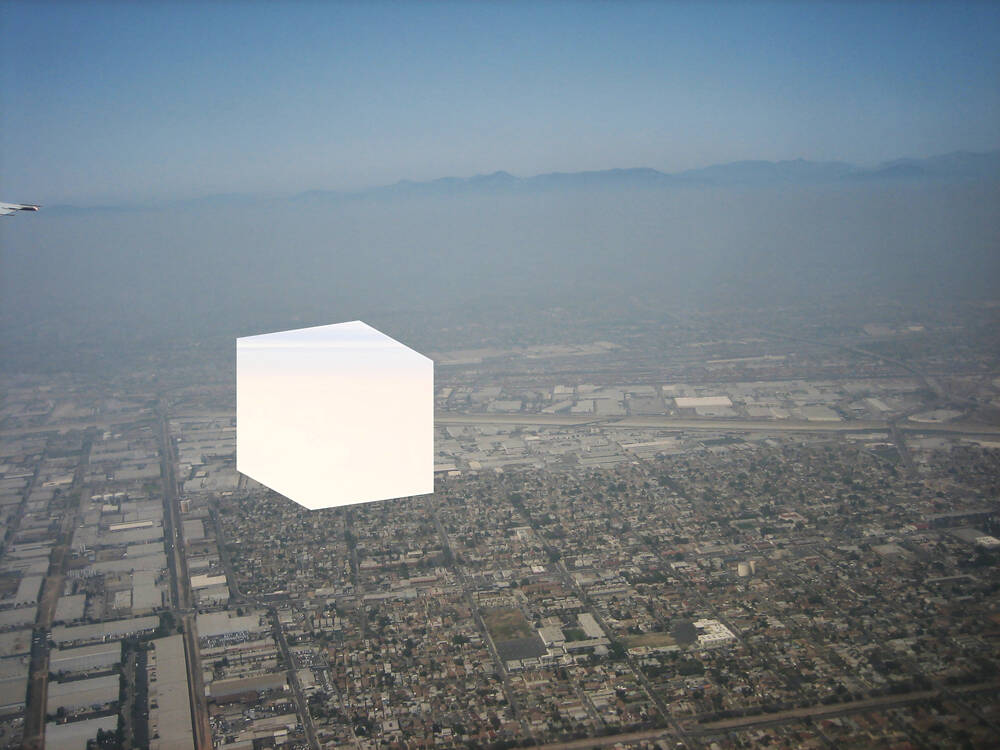

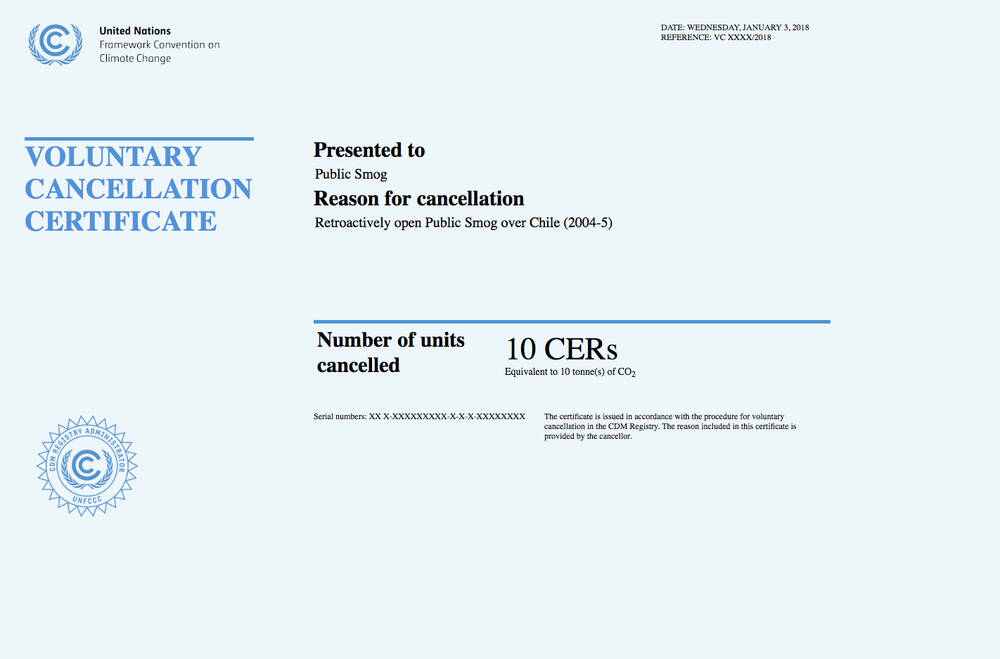

A prime example is “Public Smog”, a project by US artist Amy Balkin, which has continually evolved since 2004 with her deploying an array of different activities and visualization strategies to address issues relating to global air pollution. One important image in the “Public Smog” project is a photomontage in which a milky-white cube hovers over an image of Los Angeles shrouded in smog.

The cube symbolizes a park for everyone, which is being created by Balkin’s purchasing of emission certificates, retaining them, and thus placing them outside the reach of the polluting industrial companies keen to acquire them. The volume that thus arises over the area in which the certificates are traded and bought constitutes an ideal square space in which you can inhale something that is a matter of course, namely pure and thus non-toxic CO2.

All the complex administrative, legal, and financial processes behind “Public Smog” are summarized, documented, and updated on the attendant website, including the attempt to have the Earth’s atmosphere added to the World Cultural Heritage list and thus protected. Among all the documents, graphics, and images on the website, what really catches the eye is the photomontage with the white cube, if only because the simple shape in the space renders the invisible air tangible – not in the sense of it being tangible material, but as the “air” that is the basis for our lives – and also highlights how it has been included in a capitalist logic of exploitation.

In this regard, the two cubes in the final analysis align in more than just their analogical shapes, for both pieces show that, as regards our actions in the climate crisis, processes of nature are inextricably bound up with culture and with all of us, even if this is all too often hard to discern.

Back in the early 1960s, Haacke already recognized how different spheres interlocked in thinking about nature. Today, he can be considered one of the most important pioneers of socio-critical art.