In times of alternative facts, Damir Očko’s films seem more relevant than ever: reminiscent of Bertolt Brecht’s call for truth and exposing the lack of content of political slogans.

While two wrestlers fight to overpower each other, struggling visibly and audibly, a seemingly endless string of so-called “safe words” are read out from somewhere in the background of Damir Očko’s “Dicta II”: “Red, ceasefire, Gemüse, Mayday, Bazinga, Kassetten-Player, Pakistan, Taco, Justin Bieber, Pistols, butterfuck, green, safeword, Schroedinger, Teletubbi, lactose, chiffon, Tesla, marry me, Oppenheimer, jelly bean, pineapple, Kaugummi, lawyer, stop, attack attack”. Mainly familiar from BDSM practices, safe words guarantee that whatever is currently being done will be broken off as soon the agreed word is uttered.

And thus, in the guise of the two wrestlers, Očko has found an appropriate image, one that could not be more apt – in submission wrestling, a particular kind of martial art, the contestants use various holds to attempt to force their opponents to capitulate. And if they succeed, the defeated contender indicates his “submission” by means of a “tap out” – tapping his hands on the ground several times – and the soon-to-be winning competitor relinquishes his vice-like grip. The camera zooms in on this show of controlled force in its countless close-ups that allow viewers to experience these immensely physical proceedings, the wild tangle of sweaty bodies slapping against each other just as vividly as the barrage of words on the audio track.

Giant painted eyes stare at the viewer

“Dicta I” (2017) and “Dicta II” (2018) from the still incomplete series of works of the same name by Damir Očko, born in Zagreb in 1977, are now being presented in the SCHIRN Double Feature. In “Dicta I” – the plural of the Latin word dictum – the artist took his inspiration from Berthold Brecht’s 1935 piece entitled “Five Difficulties in Writing the Truth” which was written under the impression of the Nazi regime.

Brecht’s text was directed principally at those writers who had remained in Germany, demanding that “a writer should write the truth in the sense that he should not suppress it or keep it to himself and that he should not write anything untrue. He should not bow down to the powerful, he should not betray the weak.” A part of this edition was circulated in Germany as a camouflage publication under the title of “Satzungen des Reichsverbandes Deutscher Schriftsteller” (Statutes of the Reich Association of German Writers).

In “Dicta I” a man in theater greasepaint recites bits of Brecht’s work. Giant painted eyes stare at the viewer, although the actual lids remain permanently closed. Očko ran Brecht’s powerful words through Google Translate. The resulting text is almost impossible to follow as it is recited in fragments and the syntax has been alienated so as to render it incomprehensible.

He should not bow down to the powerful, he should not betray the weak.

The spoken sentences are reminiscent of political slogans, their content becoming more and more meaningless through constant repetition and because of the fact that their presentation always aims at a dramatic effect. As he recently explained in an interview with Metal Magazine, for Dicta I and II, the artist used techniques borrowed from Dadaism. In polit-speak, Očko continued, it is possible to recognize a kind of mimicry, by means of which in the age of “alternative facts” both untrue and meaningless assertions are presented as logical and true.

Close-ups of bodies and eyes increase the feeling of perplexity

That tricky dimension of language is also to be found in “Dicta II”, in which individual codes carry the kind of message that is the exact opposite of their actual meaning – “attack attack” as a safe word, for example. The close-ups of tapping hands and pleading eyes used in both works also reinforce the feeling of perplexity experienced by the viewer. The explanatory long shot which would allow for a more objective outside view of the proceedings fails to materialize.

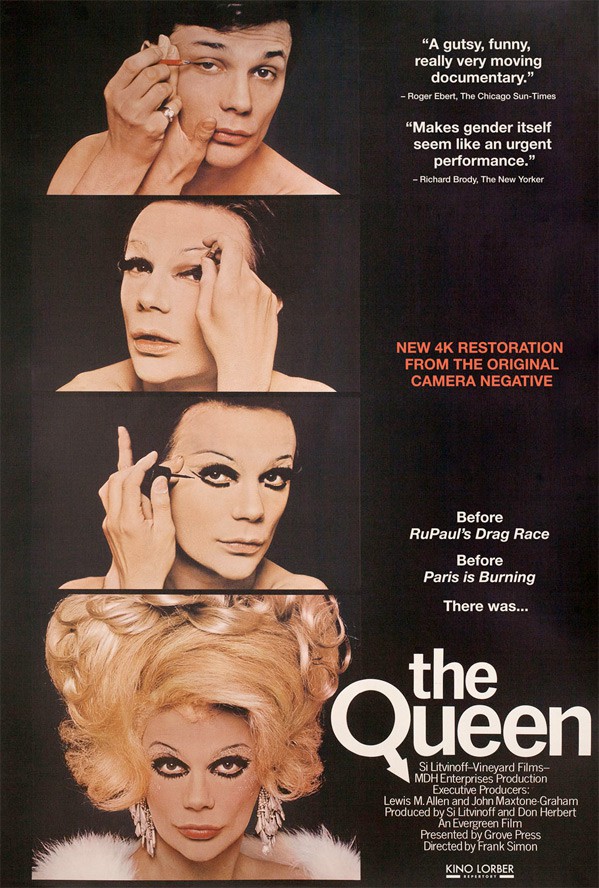

The second film Očko will be presenting is Frank Simon’s documentary “The Queen” from 1968. At the time, the film was shown at the Cannes Film Festival, in the section “Semaine de la Critique”, and a newly restored version of it was republished only recently by Kino Lorber. “The Queen” accompanies the organizers of and participants in the 1967 “Miss All-American Camp Beauty Pageant” competition in New York.

The life of the drag queen scene two years before the Stonewall Riots

Jack Doroshow, better known under his drag queen name of Flawless Sabrina, comments from the off on the circumstances of the competition’s genesis, while the camera shows the participants in a casual manner – as they arrive in New York, at the preparations in the hotel, as they exchange everyday experiences – until eventually the competition itself is shown. “The Queen” is an impressive historical document, one that provides insights into life on the drag queen scene; two years before the Stonewall Riots, in which, for the first time, members of the LGBT community rebelled on a grand scale against the arbitrary and violent raids conducted by the police.

Frank Simon, The Queen, 1968, movie poster, Image via aintitcool.com

At a time when the American Medical Association still classified homosexuality as a mental disorder and TV shows such as “RuPaul’s Drag Race” appeared unthinkable we see, in touching scenes, how the participants in this beauty pageant casually swap notes about their everyday lives – small-town experiences; their relationships with their parents after coming out; their thoughts about their own sexual identities; their homophobic rejection by the military, even though they want to serve their country. Meanwhile, the competition itself, at which guests are present of the likes of Andy Warhol, Pop Art founding father Larry Rivers, or writer George Plimpton, is a spectacle bursting with a lust for life, a little oasis in a world in which an end to discrimination still seemed a long way off.