Toni Maraini arrived at the CASABLANCA ART SCHOOL in 1964 and created the first art history program on Moroccan art from the prehistoric past to the international movements of the 20th century. In this exclusive interview, she shares her memories and provides insights into her teaching.

1. Toni Maraini, you arrived at the Casablanca Art School in 1964 and, together with Farid Belkahia, Mohamed Melehi and Mohammed Chabâa, soon formed the "core" of the school. But you were already familiar with parts of the trio before that. How did you first meet Mohamed Melehi and Mohammed Chabâa?

Toni Maraini: When Mohamed Melehi and I entered to teach at the Casablanca Art School invited by its newly appointed director Farid Belkahia, Mohammed Chebaa (nowadays spelled ‘Chabâa’) had not yet come to teach at the School; he joined us in 1966 and Mohamed Ataallah in 1968.

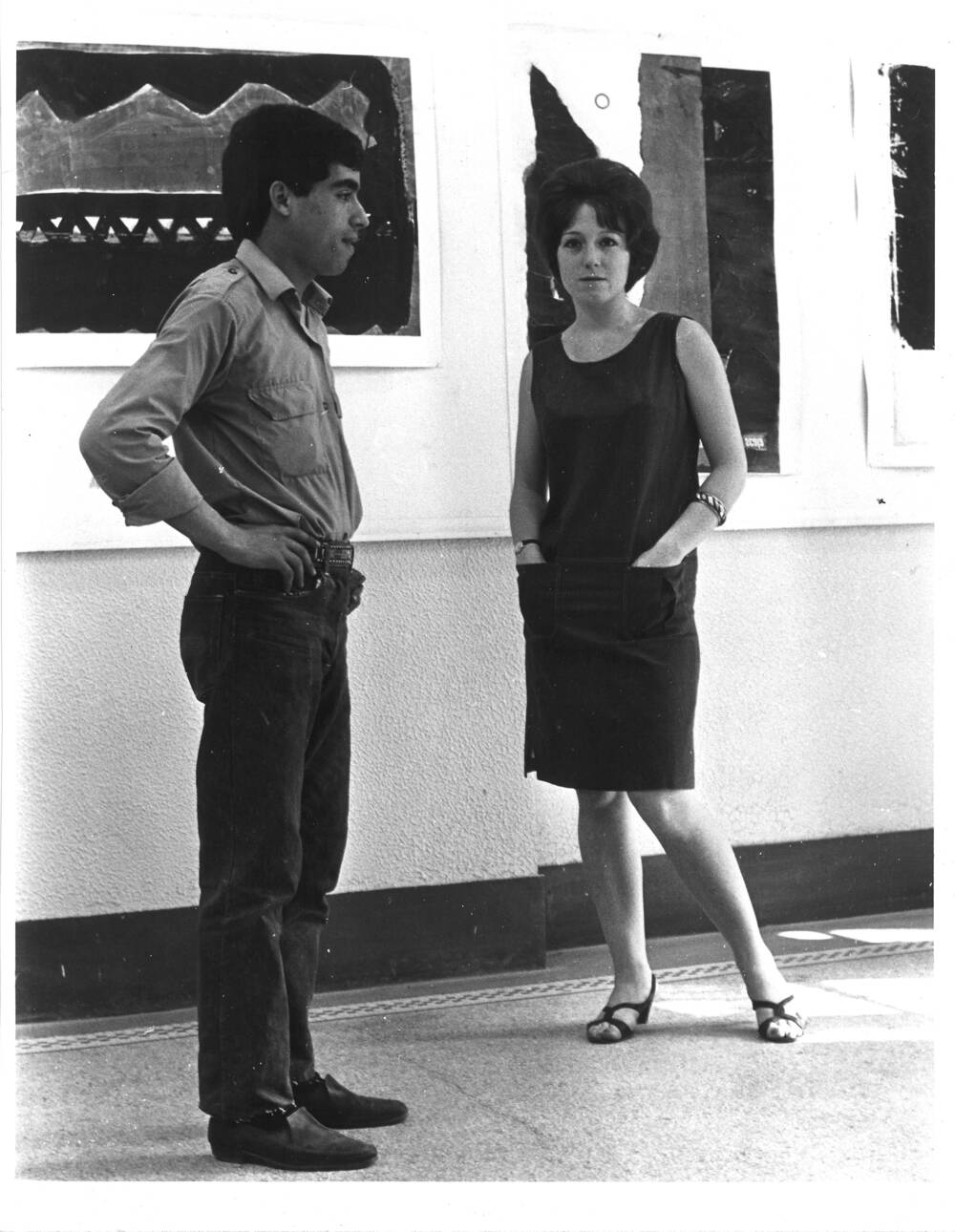

In 1964 the pioneer ‘core’ was still very small, but soon in action thanks to Belkahia’s enthusiasm and institutional commitment. He wanted to change the still strongly colonialist programs and spirit of the School, establish new courses (among which the one on Art History), apply new pedagogical teaching and fully open it to Moroccan students. We shared views, ideals and projects, and since new teachers and Ateliers were needed, we introduced our friends Chebaa and then Ataallah to Belkahia.

Melehi and I had known them when they were studying art in Rome and had become good friends. We used to gather together with other young artists, share experiences and ideas, and meet at the “Trastevere Gallery” of Topazia Alliata – my mother – where, in 1959, Melehi had inaugurated his first personal exhibition and where I first met him.

Chebaa’s works were later included in some collective shows of the Gallery, while Ataallah had in the meantime moved first to Spain then to Morocco.

When they joined us at the Casablanca Art School, our team (which in the meantime also included the artists Mohamed Hamidi and Mustafa Hafid) was more consistent and could realize some ambitious projects (manifestos, public independent actions and exhibitions in open spaces etc.) in friendly solidarity.

2. In 1963, you were in Tangier with Mohamed Melehi, Mohamed Ataalah, and Mohammed Chabâa and founded the artists' group “Algebra”, which is considered by researchers to be a kind of precursor to the School of Art in Casablanca. What was the background to this, and to what extent did Algebra's self-image differ from the future attitude of the Casablanca Art School?

Toni Maraini: Yes, our desire to form a group and engage in the art situation can be considered somehow precursor to what we later concretely realized in the School. During our meeting in Tangier in the summer of 1963 - where we met again in the summer of 1964 - my friends had taken a very critical stance on the Moroccan art situation. At that time, enhancing exotic and folklorist productions, Western cultural policy was still much conditioning local art world and market. My friends wanted to change that and assert their independent research and identity.

In solidarity with their cultural claims, I wrote an article for the local Tangier magazine “Mawaqif”. They had first mentioned the word “Algebra” in Rome; it evoked a particular legacy of rational thought. In Tangier, it was chosen as a metaphor. In the foreword to the collective Rabat 1965 exhibition which included Melehi and Chebaa paintings I wrote: “Tout un patrimoine millénaire arabe d’amour pour le rationnel et l’harmonie algébrique se manifeste dans les toiles, tout y est construit et équilibré” [“A thousand-year-old Arab heritage of love for rationality and algebraic harmony is evident in the canvases, where everything is constructed and balanced”.].

Once in the School, problems, art works and theories were certainly more varied and complex, yet the question of identity and “self-image” was still much relevant and the commitment to engage in a renovation process was not different but more concretely formulated and applied.

3. In your texts and essays, you expressed the visionary ideas of the School. At the same time, you wrote for the magazine “Souffles” and co-founded the literary and artistic magazine “Intégral”. What role did theory play within the Casablanca Art School, and was there a core message or function that could be used to summarize your writings?

Toni Maraini: During the 60s, “Souffles” was a very important breeding ground of innovative ideas, political engagement and creative collaboration among artists, poets, musicians, movie makers, intellectual etc. An altogether new innovative period of “visionary ideas” was in the making...

The group of the Casablanca School participated to it, and so did I with them. What I expressed in my writings was in tune with our teamwork, a ‘road map’ open to challenges and a concrete pursuit of “visionary ideas”. For me, it was important to document all of this. A core message?... Deconstruct colonial ideology, create conditions and act for cultural and social changes, turn to research and collaborate for a better knowledge and new perception of history, arts, tradition and modernity.

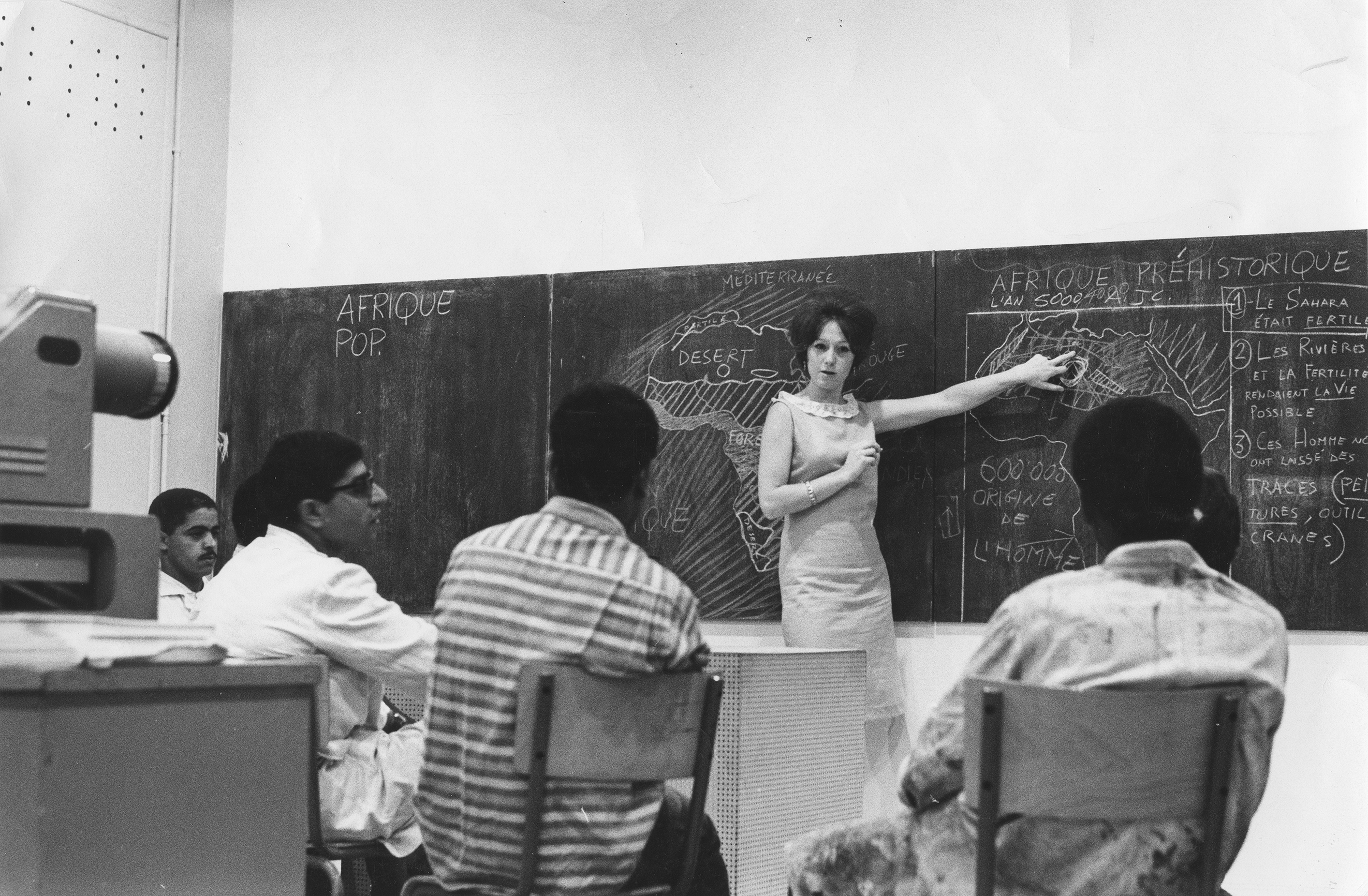

Toni Maraini teaches art history at the Casablanca Art School, 1965, Courtesy Toni Maraini Archive, Photo: Mohamed Melehi, Image via kw-berlin.de

4. With your focus on African and Mediterranean Art from the prehistoric past to the international movements of the 20th century, you were the first in Morocco to establish such a modern and forward-looking art history program. What did your classes typically look like?

Toni Maraini: Having - after the war - lived and studied for a period of my adolescence in my mother's native Sicily, I was familiar with Mediterranean society and culture. Once the family moved to Rome - which at the time (‘50s/‘60s) was a cosmopolitan city - meeting there students and artists from different Mediterranean countries (Near East, North Africa, but not only), helped me to better know the ongoing phase of modern inter-mediterranean productions; when pursuing my studies abroad (France, England, USA), I was aware of their bridging exchanges with Western artists and universal modernity. Strengthening friendships with Afro American artists - in particular Bob Blackburn, Camille Bellops and Sudan born Mohamed Omar Khalil who later all joined us collaborating with the Asilah Moussem - was particularly instructive and important.

My classes? In the beginning, there was nothing for my lessons in the small classroom... Not a slide projector, nor slides or books on Morocco, Maghreb, Africa in the School Library. I made a list of books and documents, Belkahia provided to get them and bought a good slide projector... Thanks to Melehi - who was also a photographer and had installed a photo laboratory in the School - we started to create an art slide collection. For that, Melehi and I - sometimes joined by the Dutch ethnographer Bert Flint - spent every spare minute traveling through the country and up into the remote areas of the Atlas Mountains to take pictures of sites, monuments, art works.

My lessons were initially attended by the small number of students then frequenting the School. Soon many new students, girls and boys, joined the establishment which, having become a municipal public institution, was no more an expensive elite institute. My classes were then full. Since a proper textbook was lacking, I would typewrite and print photocopies of the lessons to distribute to the students.

To better understand what they were particularly interested in, Belkahia had organized weekly reunions between them and us teachers. Students were interested in knowing Moroccan arts and traditions as well as Western modern movements and arts, practice painting and sculpture, learn about graphic design, publicity, arts applied to architecture and some art crafts such as ceramics. I dedicated some lessons to the Weimar Bauhaus; that was for the first time in Morocco.

Meanwhile, students were encouraged to organize their workshops semestral exhibitions in the hall of the School. There was thus not a “typical” Art History class but an agenda moving forward along the years! This lasted from 1964 until the beginning of the ‘70s when our group left in polemic with the new municipal political management and Belkahia had resigned from being the School Director.

5. Is there a memory of your time at the Casablanca Art School that you would like to share with us - for instance, in relation to the cultural festival Asilah Moussem Culturel, founded in 1978, in which you were heavily involved?

Toni Maraini: Difficult question!... those years are full of memories that I have tried in various ways to share (in books, articles, essays, and even short stories and poems…) and still would share, but it would be too long to do it here... and what would I choose? The Asilah Cultural Moussem was born years after we had left the Casablanca Art School... yet it somehow pursued its pioneer work and also the concept of “Présence Plastique” in public spaces.

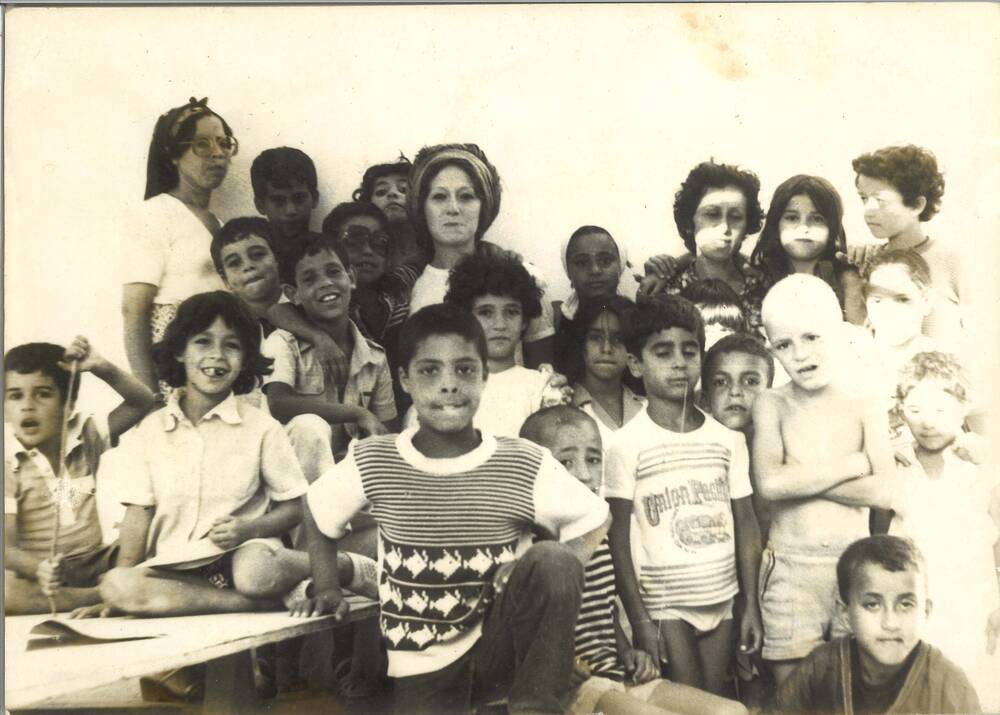

A particular memory? The Asilah summer open door Free Art Workshop (1978/1986) I organized - with tables, chairs, distribution of art materials and the help of an assistant - in the garden of the “Palais de la Culture” for children and youngsters, girls and boys of different age (from 8 to 14). Some were on vacation from school, some local children were not going to any school, some were street children with problems...they all came and mixed and worked with an extraordinary enthusiasm and desire to draw, paint, mold forms, invent and communicate! Their works were beautiful, we exhibited them. Some of the children and youngsters who had attended the Workshop have later become artists or art teachers and still write me. It was a great experience that confirmed that free art group work and expression can be an enriching therapeutic and educational practice for the young.