The Brazilian artist Igor Vidor knows the effects of German arms deliveries from personal experience. In his video work “A Praga” (2020), he confronts the sleepy town of Oberndorf am Neckar, home to Heckler & Koch, with the deadly consequences of arms exports.

In 2008 Victor Anatolyevich Bout, the so-called “Merchant of death”, was arrested and sentenced to 25 years in prison. Since the beginning of the 1990s, Bout had circumvented several UN embargoes and supplied various conflict parties on the African continent with weapons – often selling armaments to both sides of a civil war to keep the conflicts going.

BYPASSING THE EXPORT BAN: WEAPONS FROM HECKLER & KOCH

While the outrage over Bout’s exports made waves in this country as well, the events are not as far removed as you might think: The list of countries where weapons from the German company Heckler & Koch have cropped up, in spite of the existing export ban, is frighteningly long. Despite the existing embargo, they were delivered to Serbia during the Yugoslav War, just as they previously had been, for example, to Nicaragua, Sudan, Chad, or the GDR. Later on, they likewise went to Libya, Mexico, and Saudi Arabia, while Heckler & Koch weapons were also used in mass shootings in Thailand and Brazil. Regarding their deliveries, meanwhile, a company press spokesman bluntly summed up as late as 2007: “Egypt and Saudi Arabia are difficult at the moment. Africa is impossible, and Thailand can also be forgotten since the unrest.” South America and parts of the Arab world, he said, are “difficult, but ongoing”.

PANELS IMPASSIVELY PROCLAIM WEAPONS DELIVERIES

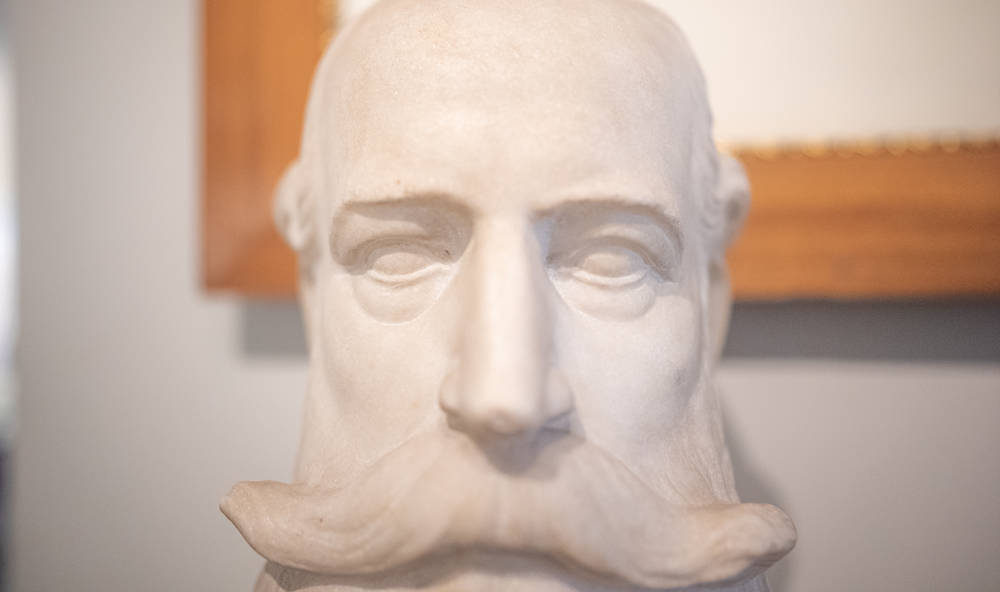

The Brazilian artist Igor Vidor knows the effects of those German arms deliveries from personal experience. In his full 30-minute video work “A Praga” (2020), he confronts the sleepy town of Oberndorf am Neckar, home to Heckler & Koch, with the deadly consequences of arms exports, combining narrative elements with archive material and self-shot footage. The camera provides a glimpse into the town’s museum which, amidst all the local color, tells the story of the Mauser brothers who founded the arms manufacturer of the same name, predecessor to Heckler & Koch, in the second half of the 19th century. Its panels impassively proclaim weapons deliveries to various South and Central American countries around the turn of the century – yet there is no mention of the purpose for which the weapons were used there. The same goes for the suffering of the forced laborers under National Socialism and the full equipping of the Wehrmacht.

Vidor then cuts to the quiet streets and peaceful houses of this small town in Baden-Württemberg. “When I was there, I was shocked by the silence that surrounded the town,” says the artist in an interview with SCHIRN MAG. The images of Oberndorf are suddenly overlaid with archival footage from Brazil: Clips of police operations, passersby fleeing, and bloody shootings break over the tranquil place from which the deadly weapons originally came.

When I was there, I was shocked by the silence that surrounded the town.

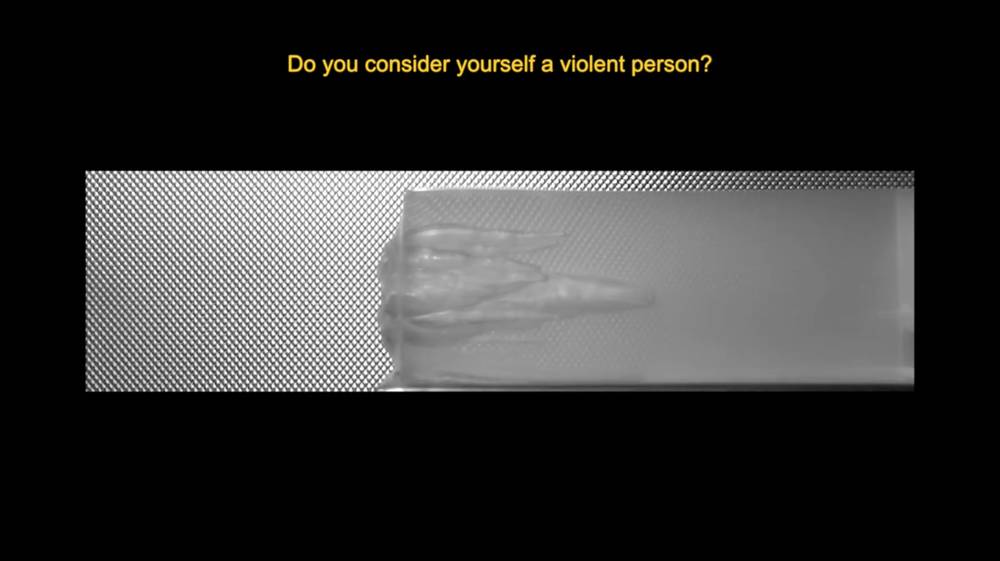

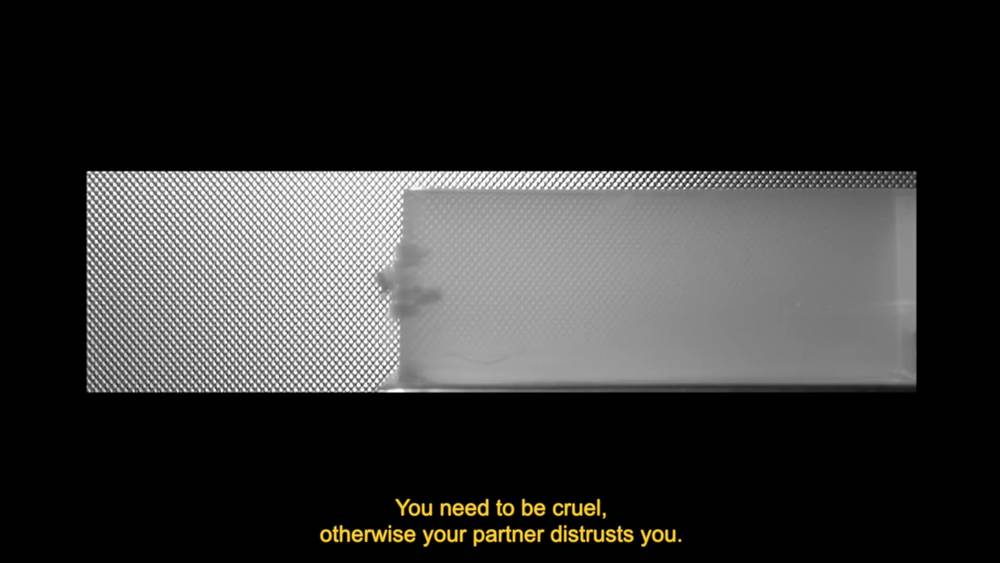

In his works, Igor Vidor repeatedly addresses the state’s monopoly on the use of force and its effects on the everyday lives of the Brazilian population, especially poor, marginalized groups. “v.a. 4598 (Rio Olympics)” (2016), for example, addresses the demolition of thousands upon thousands of apartments in poorer neighborhoods in Rio de Janeiro, which had to make way for sports facilities for hosting the Olympic Games. The work “Carne e Agonia” (2018) shows high-resolution, slow-motion footage of weapons testing. The artist subtitles these with interview statements from police officers and drug dealers, without the viewer being told exactly to whom the words can be attributed. The answers reveal the deadly madness of the so-called “war on drugs,” in which the respective antagonists are now impossible to distinguish.

PERSONAL EXPERIENCE

After the work was published, Vidor received such massive death threats that he ultimately had to leave the country. The artist also integrates the personal scope of violence in Brazil into the work in a very concrete way by means of text panels at the end of “A Praga”: In 2016, his childhood friend Rodrigo was shot dead by police officers with a Heckler & Koch gun after horrific torture. In Oberndorf, meanwhile, it is calm and tranquil, and the streets are adorned with the names of the weapons’ inventors.

As his other film, Igor Vidor has chosen the feature film “Bacurau” by the Brazilian director duo Kleber Mendonça Filho and Juliano Dornelles. The film, released in 2019 and winner of the Jury Prize at Cannes, can be classified under the genre of the Weird Western, a mixture of horror and sci-fi westerns. With the help of a large ensemble of actors, the film shows the daily life of the fictional Brazilian town of Bacurau, where the matriarch has just died. Her granddaughter Teresa (Bárbara Colen) returns to her home village for the funeral, and over the next few days learns about the problems facing the village community. The corrupt mayor of the region has turned off the water to the community; access roads are cut off by armed gangsters. At the same time, rich Western tourists led by the sinister Michael (Udo Kier) go hunting for people in the region, highly armed. The villagers prepare for the worst.

movie poster: Bacurau, 2019, Image via kino-zeit.de

A VICTORY WITHOUT A HAPPY ENDING?

Directors Filho and Dornelles stage their violent, dystopian film as an allegory of the disastrous power relations in Brazil, which here, however, brings about the unconditional solidarity of the oppressed among themselves. “Bacurau” deliberately dispenses with central heroes or heroines and instead focuses on the diversity of the village community. Colonialism, everyday violence, capitalist exploitation, marginalization – all of this culminates in the solidary uprising of the oppressed, who, however, seem to realize in the end that their story does not necessarily conclude with a happy ending just because a battle has been won.