Out and about in Brussels on the trail of René Magritte: SCHIRN MAG discovers the Surrealist side to the Belgian capital.

“Are you sure you want to come to us?” You wouldn’t expect quite so much understatement from the former home of the country’s most famous artist and its employees. Indeed while the Magritte Museum crops up in every compiled list of recommendations from hotels and tourist information offices, you will still need to be quite persistent in enquiring about the artist’s home. The similarity of the names does not help, and even Google Maps is unable to distinguish between House, Huis or Maison. The Magritte Museum, opened in 2009, is a tourist magnet in the city center, exhibiting hundreds of pictures by the Belgian painter – but the much quieter René Magritte Museum in the Jette district shows where these originated.

Anyone who so wishes can embark on the little treasure hunt that takes you to René and Georgette Magritte’s former home: If you take the bus a few kilometers out of the city, discreet signs appear shortly before the destination. A mosaic high up on a house wall shows a portrait of the painter, while on the fence there is a laminated printout showing a little running man and an oversized Magritte hat. A few houses further on and you’re finally there.

A modest home

Magritte is what you read above the doorbell at Rue Esseghem 135. This is one of just a few details that do not correspond to the original state of the dwelling because, in fact, the Magrittes lived only on the bottom floor of the multi-story brick house. “You can see that the Magrittes lived a very modest life here!” An employee opens the door to the museum, which is largely and primarily a former dwelling.

You immediately find yourself right in the middle of it, directly behind the front door begins the corridor that leads to each of the rooms: To the left is the spacious living room, through the double doors you get a glimpse of the small bedroom, and to the right on the coatrack hang a walking stick and hat, as if Monsieur Magritte had only just put them there. Once around to the left and on the other side of the corridor is the kitchen and bathroom, and before them the dining and work room – Magritte preferred painting here to in his studio, just as his habits in general contradicted much-repeated artistic clichés in certain regards.

Brought to life

While it is estimated that he created a good half of his total body of work in this location, it was his wife who earned a large proportion of the monthly household income. It was only much later that he was able to make some money out of his art; when the couple were no longer quite so young, they treated themselves to a spacious apartment in the Schaerbeek district (where you can now visit the graves of Magritte and certain other surrealists). The second financial mainstay: Studio Dongo, a mini agency for advertising and film posters, which René Magritte founded together with his brother from a base in the garden shed, aka the studio.

In the exhibition rooms on the upper floors you can later discover photos of artist friends staging theater scenes in the garden studio, or with the Magrittes having fun in their living room. Everything in this apartment seems lived-in, even manifested or brought to life, and the colorfully painted walls generously offer the very essence of the decades captured here.

Chess with Duchamp

Several details bring the Surrealist pictorial vocabulary back into today’s reality: Magritte’s windows with sky were inspired by precisely this view from the sky-blue living room on the Rue Esseghem. The dogs and birds in the garden aviary served as inspiration for images, as did the staircase, and the train in scenarios like “La Durée Poignardée”, “Time Transfixed”, appears to directly intersect the homely fireplace with its curved black heater.

A few kilometers further towards the city and you can visit a couple of places that look exactly as they did when René Magritte would frequent them: Hence, at one time, the artist faced a rejection of his paintings in the opulent art nouveau surroundings of the “Greenwich” chess café – he came here, for example, for a game with Marcel Duchamp and was met with derision both for his chess playing and for his painting style (although not by Duchamp).

24 hours of freedom

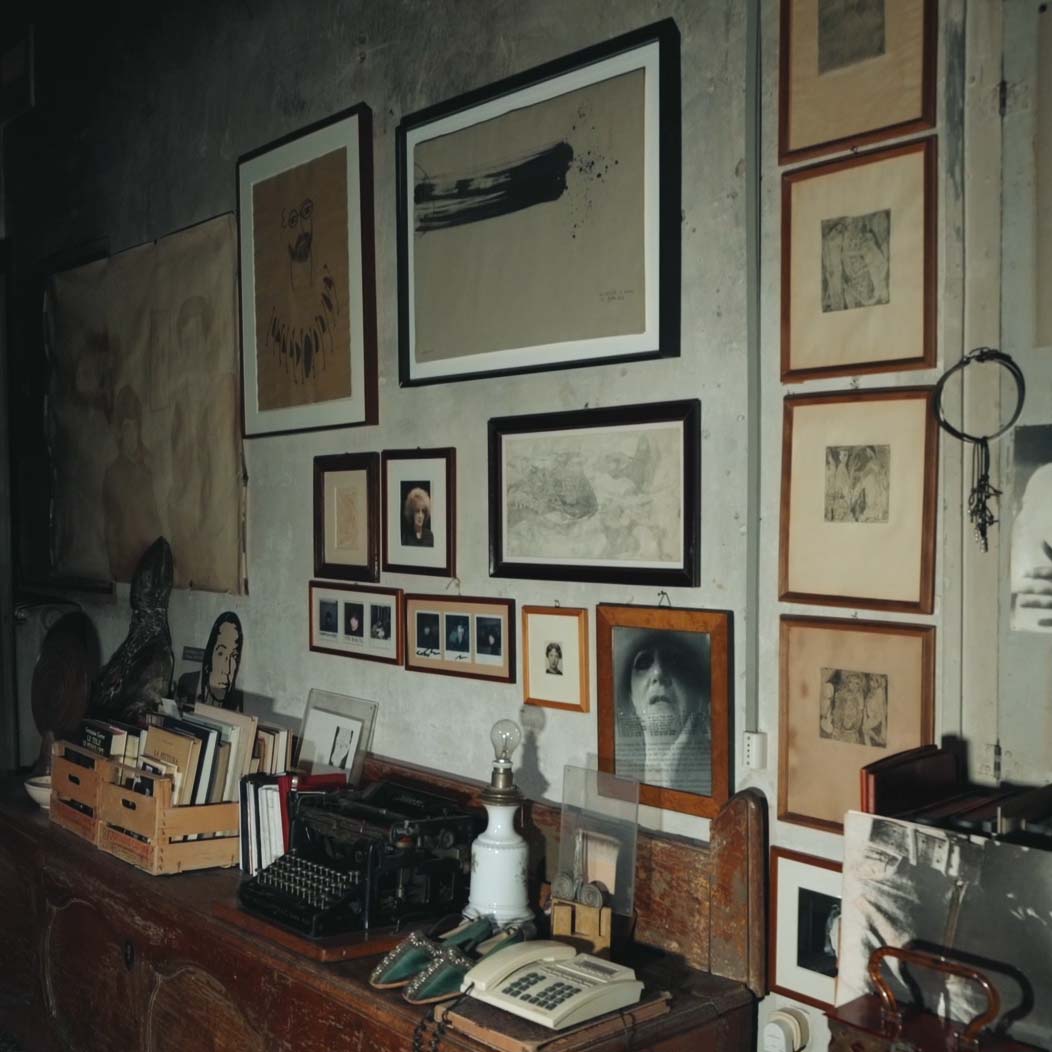

The hub of Surrealist Brussels, however, was a café-cum-bar which, like many in this city, has two names: one elegant French name (La Fleur Papier Doré) and a cutesier Flemish one (Het Goudblommeke in Papier). Here, the tradition of the artist group surrounding the then owner and gallerist Geert van Bruaene, to which René and Georgette Magritte belonged along with ELT Mesenes, Marcel Marien, Camille Goemans and a few others, lives on to this day.

On the yellowed walls, which are part of the overall monument and which, like the café, are now under special protection, can be found hundreds of originals by those artist patrons; scribbles, absurdities and small paintings, borne by van Bruaene’s motto: “Tout homme / a droit / a vingtquatre heures / de liberté / par jour.” – Every man has the right to twenty-four hours of freedom a day. A Belgian beer or a rode wijn to go with it – only smoking is no longer permitted here of course. Any fears that all that would remain of the debauchery and anecdotes would be a sad tourist trap are thus quickly assuaged: The place is magical even in 2017. Later you can take a quick look at Place Dinant, in which a few surrealist “bon mots” have been etched into the stone floor.

No photos, no photos!

With all the picturesque places that still appear as they did 50, 60 or 70 years ago, the divide could hardly be greater: Belgium still finds itself in a state of emergency which, with regard to public life, unavoidably places restrictions on the art to be found there. Everywhere you see soldiers, police and private security services on patrol, including in the Bourse Metro, the station beneath the stock exchange. It is here that you find one of the biggest Surrealist paintings you will probably ever have the chance to see: ancient streetcars suspended in a soporifically lit scene above the heads of Brussels subway users, painted by Magritte’s artist colleague Paul Delvaux.

Just enough time for a few snapshots, before the security service accosts me: no photos, no photos! I’m allowed to keep those I have already taken. With a bit of convincing, you may then also be able to get a glimpse of two further frescoes by the Brussels surrealists, in an area that is neither public space nor artistic sphere: In the Square Brussels Meeting Center, two large-format wall paintings face each other – one is by Paul Delvaux, the other by René Magritte.

Seeing nature anew – through a cube

In his early work, HANS HAACKE addressed the relationship between art and nature as well as the social interest in the reciprocal relationship between...

The film to the exhibition: Hans Haacke. Retrospective

A legend of institutional critique, an advocate of democracy, and an artist’s artist: The film accompanying the major retrospective at the SCHIRN...

A new look at the artist – “L’altra metà dell’avanguardia 1910–1940”

With “L’altra metà dell’avanguardia 1910–1940”, in 1980 Lea Vergine curated an exhibition at the Palazzo Reale in Milan that was one of the first...

Non-human living sculptures by Hans Haacke and Pierre Huyghe

In his early work, HANS HAACKE already integrated animals and plants as co-actors into his art. In that way he not only laid the foundations for a...

CURATOR TALK. CAROL RAMA

SCHIRN curator Martina Weinhart talks to Christina Mundici, director of the Carol Rama Archive in Turin, editor of the first Catalogue Raisonné and...

Freedom costs peanuts

HANS HAACKE responded immediately in 1990 to the fall of the Berlin Wall and turned a watchtower into art.

The film to the exhibition: CAROL RAMA. A REBEL OF MODERNITY

Radical, inventive, modern: The film accompanying the major retrospective at the SCHIRN provides insights into CAROL RAMA's work.

Now at the SCHIRN: Hans Haacke. Retrospective

A legend of institutional critique, an advocate of democracy, and an artist’s artist: the SCHIRN presents the groundbreaking work of the compelling...

Carol Rama’s Studio: A nucleus of creativity

CAROL RAMA determinedly forged her own path through the art world. Her spectacularly staged studio in Turin was opened to the public only a few years...

PANEL: POLITICAL ACTIVISM BY SELMA SELMAN

Hosted by Arnisa Zeqo, Amila Ramović and Zippora Elders speak with the artist Selma Selman about her artistic career, the exhibition SELMA SELMAN....