The feature film “Leaning Into The Wind” about British land artist Andy Goldsworthy is a successful meditation on transience.

Sometimes there are those moments when you leave the cinema, and reality and film briefly coincide. When the darkness of the movie theater seeps through, only to quickly disappear again behind the closing door. After the full 90 minutes of “Leaning Into The Wind - Andy Goldsworthy” there is precisely such a moment, when the extremely leisurely paced portrait of the artist Andy Goldsworthy, who is filmed primarily in nature, is suddenly followed by the traffic noise of bustling reality. It’s in moments like this that one is briefly inclined to agree with the statements like “I like grey, calm days”, that Goldsworthy comes out with.

Following on from “Rivers and Tides – Andy Goldsworthy Working With Time”, “Leaning Into The Wind” is the second film that cameraman and director Thomas Riedelsheimer has dedicated to the artist, who is among the best known champions of Land Art. More than ten years passed after “Rivers and Tides” before the two men met once again in Scotland in 2011 and decided they wanted to make another film together. As a result, here a proven formula is reestablished, as Goldsworthy remains the likable eccentric and Riedelsheimer knows how to capture the aura of extraordinary artistic figures and their works with a calm gaze, as he also demonstrates in “Breathing Earth” and “Touch the Sound”.

Dropping out of the world

“Leaning Into The Wind” is thus something of a documentary sequel, which shows the hyper-sensitive nature-lover and romanticizer Goldsworthy and his work in a later phase of life. Riedelsheimer and the artist meditate on transience to the sounds of a similarly sedate soundtrack by Fred Frith. In visual terms the theme is manifested right at the beginning, when in time-lapse we see ruptures – one might almost say wrinkles – form in a tree Goldsworthy has encased in clay. This theme continues throughout the film when, on multiple occasions, Goldsworthy lies on the ground in the rain, leaving behind a quickly disappearing rain shadow, or retreats to his favorite place in the forest, where he decorates a dead tree stump he has been working on for some time with leaves and branches.

At no point is any secret made of the fact that Goldsworthy is someone who has dropped out of the world, who lives the slow movement with every fiber of his being. Occasionally his anecdotes and reminiscences seem like the stuff of sentimental calendar maxims, setting an awkwardly romanticizing tone for the film overall. This is forgotten, however, as soon as Goldsworthy – be it in the city or in his rural Scottish homeland – again climbs like Spiderman through a long hedge or tackles his next work with childish curiosity and manual dexterity. His existing works made of stones, branches or leaves never fail to be visually impressive and moving.

Clarity in chaos

It is a downright one-sided utopia that Riedelsheimer and Goldsworthy formulate here, since the actual art world plays no role whatsoever in their film. Yet it’s precisely this detachedness that gives “Leaning Into The Wind” a fable-like quality: Namely, the film gets its title from a work that involves Goldsworthy leaning into the wind on a Scottish hillside and trying to maintain his balance. He tries to find the precise point at which the wind carries him and for a second everything is held in balance. For Goldsworthy it’s a brief moment of clarity amid the chaos. Just like in real life.

At the mercy of waiting

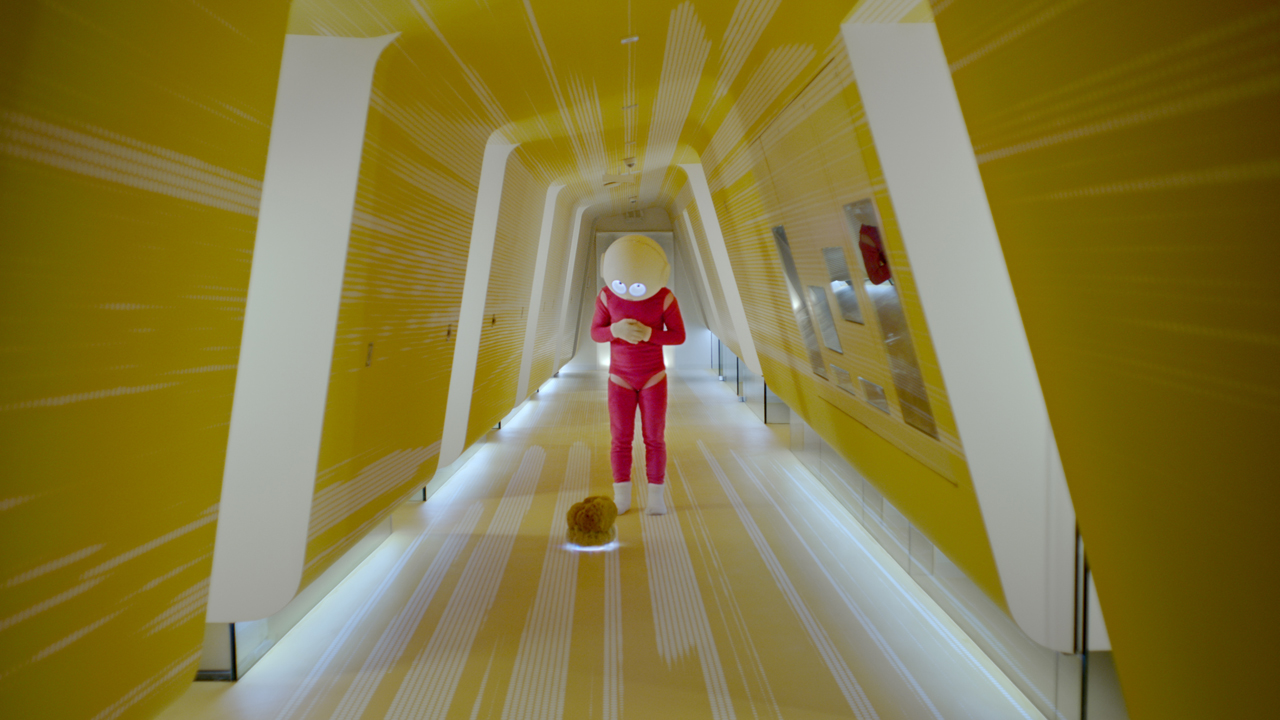

Artist Bani Abidi is dedicated to the dark absurdities of everyday life. In her video work "The Distance from Here" bureaucracy takes over and waiting...

“Please don’t make a film about Godard!”

A film about filmmaking sounds a bit meta. But Kristina Kilian’s video work takes us on a ghostly journey through Godard’s Germany after the fall of...

Black is not a Color

In a film series, Oliver Hardt combines the themes from Kara Walker’s work with the perspectives of Black people in Germany. In conversation with...

How do we Remember?

In which places does history become visible? And what do we remember at all? Maya Schweizer begins her search for clues in the sewers and slowly feels...

Film highlights from South and North America

How can we break with the power relations of the past and create a decolonial future? A look at the representation of Indigenous women in film.

Must See: The World of Gilbert & George

Eccentric, fascinating, repulsive, entertaining and full of symbols: “The World of Gilbert & George” is a collage about the artifice of everyday life...

Spring is coming, and so is Magnetic North

For the first time in Germany, principal works from Canada’s major collections are on view at the SCHIRN. At the same time, the exhibition examines...

A Revolution in Iranian Dance

After the Iranian Revolution a nationwide dance ban was issued. It was subverted by smuggled video cassettes of dancer-in-exile Mohammad Khordadian,...

How to perform painting

This is perhaps the best way to describe the work of video artist Angel Vergara: Art history meets pop culture, the artist himself appears as a...

About the resistance of our bodies

Hypnotic dances and hybrid beings in cyberspace: Video artist Johanna Bruckner transforms the human body into digital matter.

More than a Honeypot

Young, beautiful and dangerous: the prototype of the Bond Girl still shapes the cliché of spies. Author Chloé Aeberhardt on the reality of espionage...

How to create the unexpected

About life in exile, anarchic art, and the “black milk” of the earth: The art historian Media Farzin met her old friends Ramin and Rokni Haerizadeh...

Why so cryptic?

What lies behind the title of the exhibition by Ramin Haerizadeh, Rokni Haerizadeh and Hesam Rahmanian. And why humor is sometimes the best criticism....

Schirn Preview: Ramin Haerizadeh, Rokni Haerizadeh and Hesam Rahmanian

Exuberant, funny, eccentric and full of allusions: The Schirn presents the Iranian artist collective's first solo exhibition in Germany.

The Future of Video Art

Six international video artists present their new works. An exchange about new trends and forms of expression in film.