As long as there are wars, there will be films that tell their stories. These motion pictures’ approaches to the gruesome theme are sometimes humorous, sometimes dramatic. An overview by the SCHIRN MAG.

If you believe the French media and speed theorist Paul Virilio, developments in media technology are rooted in military and battle technologies. Hence, in his book “War and Cinema”, which appeared in Germany in 1986, he describes the camera as an amalgamation of eye, engine and weapon. Aim, fire, and the image is burned onto celluloid or, in the digital age, onto the memory card. Today’s drone technology, which provides reconnaissance images in theatres of war, yet also provides breath-taking camera settings in feature and documentary films, makes Virilio's assertions more than tangible.

All war movies are anti-war movies.

Film as an artistic medium stands on the good side of the power here and indeed, ever since its infancy, has always been used explicitly as a messenger of peace. As early as the First World War, films were being produced that denounced combat operations and stood up for pacifistic values. Charlie Chaplin’s “Shoulder Arms” from 1918, for example, lays bare the horror of war with excessive satire. Sadly, the history of the 20th century shows that humans are not able to learn from their mistakes. It’s no wonder, therefore, that now there are (and indeed must be) countless films that deliberately tackle the topic of war from the perspective of a desire for peace.

Classic war and anti-war films

The genre of war and/or anti-war films is virtually as old as cinema itself. In explicit images, the films tell of the combat operations, and of the horrific fates of individuals and brigades. As iconographies of madness, they denounce war, as illustrated by certain American classics. For example, In Lewis Milestone’s anti-war epic “All Quiet on the Western Front” (1930), based on the novel of the same name by Erich Maria Remarque, the initially nationalistic-euphoric figures surrounding Paul Bäumer in the trenches of the World War I are brought down by the atrocious reality.

In “Full Metal Jacket” (1987), Stanley Kubrick showed that even the preparations for combat operations in Vietnam amounted to an inhumane hellhole, in which bullied recruit Leonard Lawrence, alias Gomer Pyle, is sent mad and blows off his own head in the toilet. Moreover, the hellish ride on the atom bomb at the end of Kubrick’s satirical classic “Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb” (1964) about the Cold War gradually became one of the best known portrayals of the madness of war. In his masterpiece “Apocalypse Now” (1979), Francis Ford Coppola sends a squad on a direct path to the heart of darkness, to madness personified, namely Colonel Walter E. Kurtz, played by Marlon Brando, whose utterly distorted world view governs a band of madmen in the depths of the Vietnamese jungle.

The famous Ride of the Valkyries

“All war movies are anti-war movies,” explained Coppola in an interview with The Times. The fact that you nevertheless need rational recipients for films to be read this way is demonstrated impressively in Sam Mendes’ Film “Jarhead” (2005): Here, Coppola’s classic film becomes a propaganda tool when the platoon surrounding Anthony “Swoff” Swofford (Jake Gyllenhaal) works itself into a frenzy celebrating the famous helicopter attack from the Coppola movie that was accompanied by Richard Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries”.

Many of the abovementioned films tackle, to a greater or lesser extent, the trauma characters suffer after returning from the battlefield as part of the classic narrative structure of education – combat operation – return. The returning soldier is generally portrayed as an emotional cripple who is no longer able to function in society. You only need to think of “The Deer Hunter” (1978), in which Michael (Robert De Niro) even returns to Vietnam voluntarily. The beginning of this year saw the release of Ang Lee’s “Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk”, a film that varies this structure in an original way: Billy, who has returned from the Iraq War, and his comrades are celebrated in an absurd victory tour, almost a media band-aid for the trauma of a nation. The climax is an appearance by the eight soldiers in the halftime show of a football game. With sometimes satirical exaggeration and flashbacks to battle situations, the trauma felt by Billy, who experiences the media spectacle as if in a trance, becomes palpable. “It’s kind of weird being honored for the worst day of your life,” he says at one point.

Film in the service of peaceful coexistence

In “The Messenger” from 2009, Oren Mormann concentrates entirely on the “aftermath”, by keeping one eye on the enormous voids that wars leave in the realities of those involved in them: With little pathos, Mormann tells the story of war hero Will (Ben Foster), who spends the last three months of his military service with the “Casualty Notification Team”, and together with Tony (Woody Harrelson), must inform families of the deaths of their loved ones. Their reactions, which range from objective sobriety to outbreaks of tears and even attacks on the “death angels”, are a reflection of post-war suffering. This agitative drama was presented with the Peace Film Prize at the Berlin Film Festival. The prize was initiated in the UN Year of Peace in 1986 by the Berlin Peace Group and, ever since, has been presented at the film festival to works which place “the aesthetic medium of film in the service of peaceful coexistence and social engagement”.

One extraordinary example from an aesthetic perspective is “Waltz with Bashir” (2008), by the Israeli director Ari Folmann. This is actually an animated film in which Folmann’s alter ego of the same name attempts to reconstruct his participation in a deployment during the Lebanon War, which he has been suppressing. The director was himself deployed as a soldier during the first Lebanon War and his film is based on real events. Animated Folmann eventually finds out that he and his comrades indirectly supported a massacre by firing a flare shell. In this abstract, but nevertheless very intense animated world, the real horror literally bursts in when, towards the end of the film, excerpts of documentaries showing those murdered in the Sabra and Schatila massacre appear.

Documentary films for peace

By its very nature, the documentary film plays with different material than the fictional film, since no fiction is interposed, but rather the involvement of contemporary and eye witnesses articulates authenticity: Yes, this horror really did exist – it is part of our reality! One film that does this in a particular way is Joshua Oppenheimer’s documentary film “The Look of Silence” (2014), which likewise won the Peace Film Prize and tackles the genocide carried out by the military and private militia in 1965/66 in Indonesia, to which at least half a million supposed communists fell victim. In the film the optician Adi Rukun, whose brother was killed in the massacre, interviews perpetrators from that time who have never been brought to justice and, in some cases, hold high office. Despite obstacles, the film was screened and discussed several times in Indonesia and has made an active contribution to bringing to light a long hushed-up chapter in the country’s history. As early as 2012, Oppenheimer dealt exclusively with the perpetrators of the genocide in the likewise extremely haunting “The Act of Killing”, having them recreate their horrific acts in sometimes disturbing reenactments.

As long as there continues to be wars in the world, there will also be films that tell their stories. And even if film cannot change the world directly, like other works of art, it has the power to denounce, to open our eyes and to show what cannot be shown.

At the mercy of waiting

Artist Bani Abidi is dedicated to the dark absurdities of everyday life. In her video work "The Distance from Here" bureaucracy takes over and waiting...

“Please don’t make a film about Godard!”

A film about filmmaking sounds a bit meta. But Kristina Kilian’s video work takes us on a ghostly journey through Godard’s Germany after the fall of...

Black is not a Color

In a film series, Oliver Hardt combines the themes from Kara Walker’s work with the perspectives of Black people in Germany. In conversation with...

How do we Remember?

In which places does history become visible? And what do we remember at all? Maya Schweizer begins her search for clues in the sewers and slowly feels...

Film highlights from South and North America

How can we break with the power relations of the past and create a decolonial future? A look at the representation of Indigenous women in film.

Must See: The World of Gilbert & George

Eccentric, fascinating, repulsive, entertaining and full of symbols: “The World of Gilbert & George” is a collage about the artifice of everyday life...

Spring is coming, and so is Magnetic North

For the first time in Germany, principal works from Canada’s major collections are on view at the SCHIRN. At the same time, the exhibition examines...

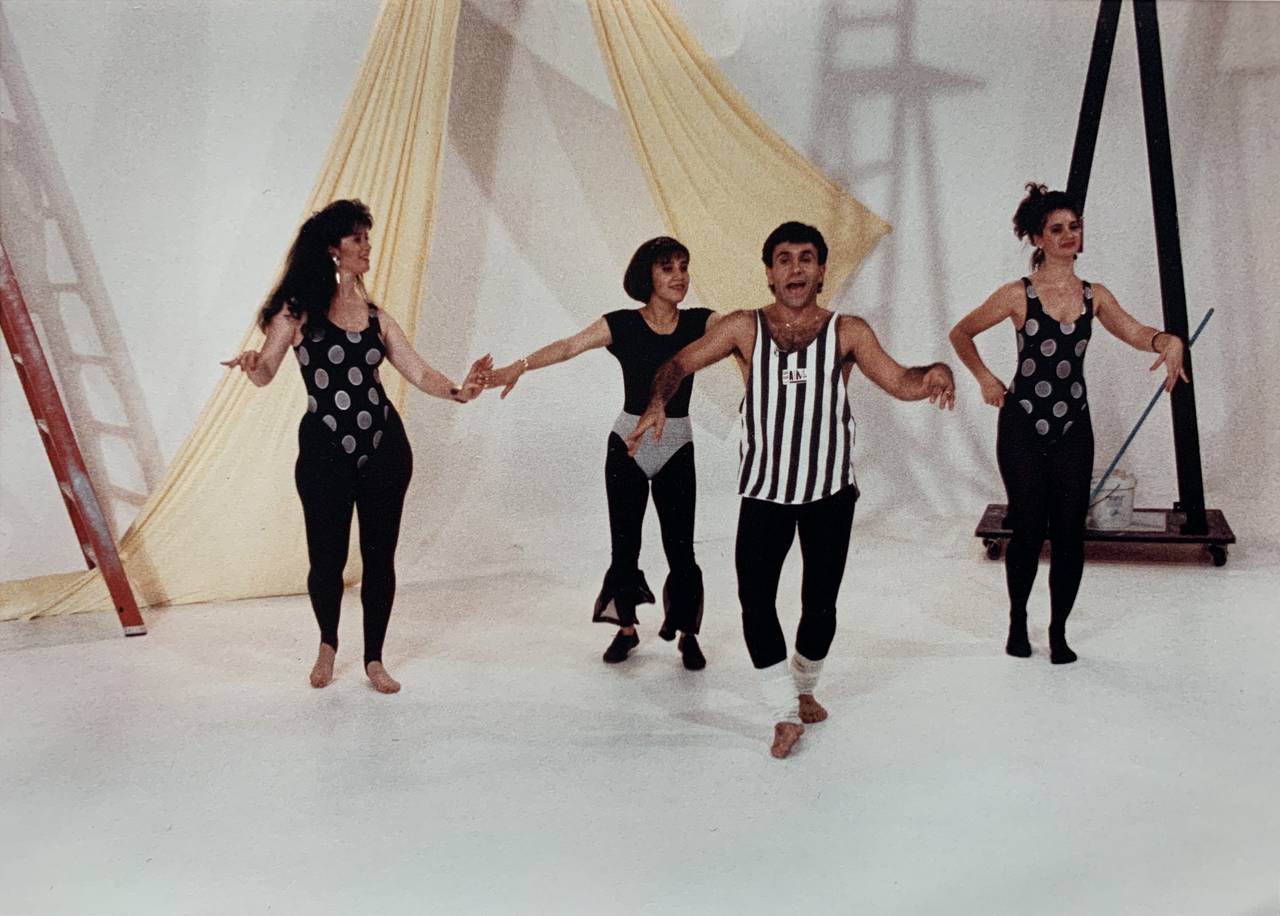

A Revolution in Iranian Dance

After the Iranian Revolution a nationwide dance ban was issued. It was subverted by smuggled video cassettes of dancer-in-exile Mohammad Khordadian,...

How to perform painting

This is perhaps the best way to describe the work of video artist Angel Vergara: Art history meets pop culture, the artist himself appears as a...

About the resistance of our bodies

Hypnotic dances and hybrid beings in cyberspace: Video artist Johanna Bruckner transforms the human body into digital matter.