Marie-Theres Deutsch was born in 1955 in Trier at the central western tip of Germany, into a family of five women and a father who was an architect. At the age of six, she knew: “I’m going to be an architect. Period.” In an interview with us, she reveals how things then worked out.

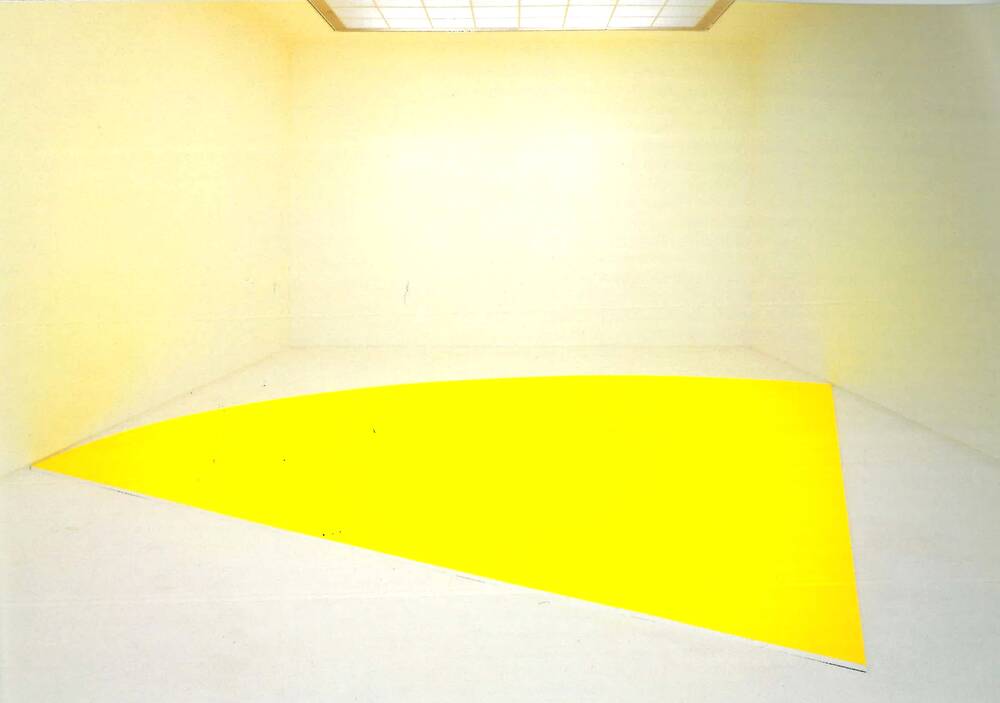

In 2024, Fondation Louis Vuitton featured a pop-up of a former Frankfurt building: the original Portikus, built in 1987 to plans by Marie-Theres Deutsch. The Frankfurt-based architect found out about this by pure chance through an artist friend, but it immediately brought memories flooding back. On the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the birth of US artist Ellsworth Kelly, his famous piece “Yellow Curve” went on display at the museum in Paris, which chose to show it within a reconstruction of the interior where he had exhibited the work in 1990 in Frankfurt, and this reconstruction was faithful to the original down to the very last millimeter.

Marie-Theres Deutsch was born in 1955 in Trier at the central western tip of Germany, into a family of five women and a father who was an architect. At the age of six, she knew: “I’m going to be an architect. Period.” And because in German the word “architect” was masculine, she of course used the descriptor for her own profession. After studying at a university of applied sciences, she progressed to the Städelschule in order to learn architecture from a very different perspective. Fast forward a little, and Deutsch had already designed the original Portikus, the Städelschule’s first exhibition space. This was followed by projects throughout the city and beyond, such as the Städelschule guest apartment, the revitalization of the Main riverside and of the building where she lived and worked. About 80 percent of her work involves modernizing existing structures. This requires a lot of craft skills, she says, and the designs are often defined by the costs. She attempts wherever possible to use existing resources. “A project in Westend converted an old coal cellar into a marvelous bistro. It required quite a lot of effort, but the location justifies that. Fundamentally, in our cities we should preserve what is economically viable and can still be used.”

Ms. Deutsch, we’re sitting here in your house, which is also your architecture practice and home to you and your husband, an artist couple, and the guest apartment for Schauspiel Frankfurt. It has a small footprint, merely eight meters wide and 143 sqm in size – a gap that was considered impossible to fill with a building.

Marie-Theres Deutsch: Yes, it had been turned into a pile of rubble in a 1944 bombing raid. Next door were four bars where the emergency exits all used the plot, so there were fire protection issues, too. Because the site was only eight meters wide, no investor was interested. I made virtue of a necessity and rerouted the emergency exits through the house. The bars have since closed down, but up to eight years ago you could still walk from our courtyard along our corridor out onto the street. That was entered as an encumbrance in the approved plans.

Meaning in an emergency barflies could have fled through your private home to the outside?

Marie-Theres Deutsch: Yep! There are panic buttons that in an emergency give you access from our courtyard to the corridor. Quite normal. Not a problem. I like long corridors (laughs).

The location is quite unique: medieval, a party zone, binge-drinking tourism. In 2013, you went on record saying that “three garage doors had already been kicked in”. Why Alt-Sachsenhausen of all places?

Marie-Theres Deutsch: I had never previously frequented the place. The Municipal Planning Dept. suggested to my husband and me that we should take a look around here. They were hunting for architects who were prepared to design buildings for an old setting. And to pre-empt the question, today I would approach the project exactly the same way. It’s only loud here on Friday and Saturday nights. We sleep at the back of the house and have well-insulated windows, so there’s no noise issue. A lot can be done with technology to constrain noise pollution.

What does catch the eye, however: It’s dirty outside and increasingly so. Nowadays, like in the district round the central railway station, in the morning there are empty laughing gas canisters all over the place. Sometimes I chat with the young people and get invited to try it out for myself. What I think is great is that everyone knows each other here. I moved here from Westhafen, my husband from Osthafen; each of us had a large apartment. We both lived anonymously in apartment blocks. Living in Alt-Sachsenhausen is like living in a village, with people from all over the world. And it’s not much more than a stone’s throw from the Römer.

You founded your own architecture practice at an early date and in 2025 are celebrating your 40th anniversary. So why architecture?

Marie-Theres Deutsch: I have often told the story, but it’s worth retelling. Imagine the following situation: Four daughters fight it out for their father’s attention. I built Lego houses and drew ground plans, and that guaranteed me my dad for myself sometimes even for an hour. He was an architect and thus I gradually became immersed in the subject. At the age of six, I knew: I’m going to be an architect! Period.

After university you started studying architecture at the Städelschule, too. Did that complement your first degree or was it completely different?

Marie-Theres Deutsch: It was clear to me from the outset that I would complete my first, technical degree very quickly. At the academies it was a precondition for being accepted. I found myself in a completely different world and stayed on in Frankfurt. There were wonderful people at the Städelschule, and initially the curriculum was very interdisciplinary. Günter Bock and Peter Cook headed the architecture class, Peter Kubelka “experimental film” and “cooking as art”, and Hermann Nitsch was guest professor. The entire situation simply captivated me.

In the 1970s, at the Frankfurt University of Applied Sciences you primarily learned the technical know-how, from which I was of course able to derive benefits. For a young person, however, it somewhat blurred your judgement as a lot centered around the question of “How can I use this specific material?” In architecture, though, the purpose is to find the roots of the place, to tease out what the history is and to “play” with that knowledge. What is immensely important is not just to copy the stylistic means of the past but to establish what is special about the place and to transform that into today’s world. So don’t ask me about Frankfurt’s New Old Town (laughs). That’s an example where you can see how great the difference can be between urban planning and architectural quality. I feel the modified historical urban footprint is persuasive, and the high visitor figures demonstrate that the place is an attraction. But the individual buildings are bad copies of their predecessors, and only two of the buildings have in my opinion achieved the requisite transformation.

At the art academy, I learned from teachers such as Günter Bock and Peter Cook to construe architecture as a response in the here and now. We’re intensively trained to do that. As a young architect, I benefited from both curricula: at the Städelschule I was able to learn how to escape the confines of the technical approach and to tackle the design process in a freer mode.

Tell us about one of your best-known projects that now no longer exists in the urban fabric, namely the original Portikus exhibition hall. It was erected in 1987 on the site where today’s Literaturhaus stands. A “flying” building that was originally granted building approval for only two years, but the permit was forever being extended. It eventually made it to 17. You were very young at the time, at the very beginning of your career. So how did it all happen?

Marie-Theres Deutsch: Kasper König’s attitude played a key role. He thought outside the mainstream box. We had heard from Thomas Bayrle that Kasper was interested in signing on in Frankfurt. But under the condition that he could exhibit at a place of his choice. So where could that be? Back then, the three of us drove over the bridge crossing the Main, where today’s Literaturhaus is located – Manfred Stumpf, Thomas Bayrle, and I. An artist was just shooting a film scene there. A huge halogen spotlight was shining on the then ruins, and one of us exclaimed: “That’s it!” That moment enabled us to experience the place in a new way.

Thomas told Kasper about our idea – and that it was tough. The ruins were a monument to the soldiers killed in World War II and stood abutting the inner-city ring road featuring parkland rather than the razed city ramparts. To this day, the law states that no building may be erected on that ground. Kasper immediately championed the idea. A marvelous place, really close to downtown and yet off-center. Homeless people frequently used the area. Kasper and Thomas met in Frankfurt for a meal, and by pure chance I wandered into the same restaurant that day. Thomas spotted me and called out, “There she is! Here, Kasper, your architect!” That was how we teamed up. Those two moments were decisive. The idea thus evolved that was in no way related to the later name of the place: Portikus. The line of riverside museums had just been completed, places with a high entrance threshold. Kasper wanted exactly the opposite: an uncomplicated, vibrant place that would exclude the establishment’s self-conceit.

A few years later, adopting precisely that mindset, I developed many small places along the riverside downtown. To this day, the idea is successful, as the Main riverside is highly popular with all its small bars. It’s not just locals who love those easily accessible relaxed spaces directly on the waterside.

How was your undertaking viewed outside the art bubble?

Marie-Theres Deutsch: My plans for the Portikus were controversial even among those at the Städelschule. My former teachers accused me of showing a lack of respect. “…She simply slaps the art box down directly next to the ruined wall …,” as some put it. “…But it’s a monument to the soldiers who were killed!”, they said. I was slammed for being “cheeky”. The Municipal Dept. of Building insisted that “she’s much too young and inexperienced, it can’t work out. We’ll do it ourselves!” I got really mad. What followed was a really intense working weekend with colleagues and fellow students in the knowledge that “we’ve got a weekend only and will plan the design on a scale of 1:50 including all the details ….” No sooner said than done. Early Monday saw me standing with the filled tube of plans at the entrance to the Municipal Building Dept. waiting to intercept the guys. I was condescendingly taken along to the meeting. There I presented our carefully planned proposal. I was fortunate enough to combine commitment with audacity, and my technical knowledge from my days at the University of Applied Sciences once again proved a strength.

Hilmar Hoffmann as City Deputy Mayor in charge of Culture and Hans-Erhard Haverkampf as City Building Executive supported the project. It was clear that the City of Frankfurt really wanted to attract Kasper König, and the construction manager at the municipal FAG corporation, which handled site management, liked me. I acted very masculine and of course smoked the cigars I was offered. It was quite a struggle: How will I get due recognition as a young female architect? Will I be able to defend my corner? It really was like that. But it worked out.

A few years ago, Deutsches Architekturmuseum held an exhibition entitled “Ms. Architect”, which for the first time attempted to take stock of the work of female architects in a field originally dominated by men. In a film shown there, you talked about your experiences.

Marie-Theres Deutsch: Yes, I talked about how difficult it was back then. My daughter was born while I was still studying at the Städelschule. My teacher Peter Cook said: “There are no children allowed at our academy!” I wasn’t impressed. My father died young, and I thus grew up in a house with five other women in the arch-Catholic, bigoted conservative world of Trier. Back then, we soon learned what we as young women had to do: combine a little brashness with swiftness and provocativeness – in order not to get crushed by things.

A question that probably no one would ask a man: Was that the reason why it was so clear to you that, as a mother and architect, you would freelance?

Marie-Theres Deutsch: Well, back in the 1980s many women with whom I was acquainted said, “I’ll manage alone!” Who needs a husband who simply wants to have his say all the time?

We mothers helped each other out, always alternating. The home and the office were often only separated by a door. On average, there were ten staff members in the office, and one of them always cooked for the team in the apartment. Or played with my daughter. After a few years, that frequently became too much for me. So I kept the home and the office far more separate, with the result that my child was often alone at home for too long.

In everyday work, the first step is to identify requirements and then to start on the design. Competitions are part of that. Are there buildings you really would have loved to build but which never got realized?

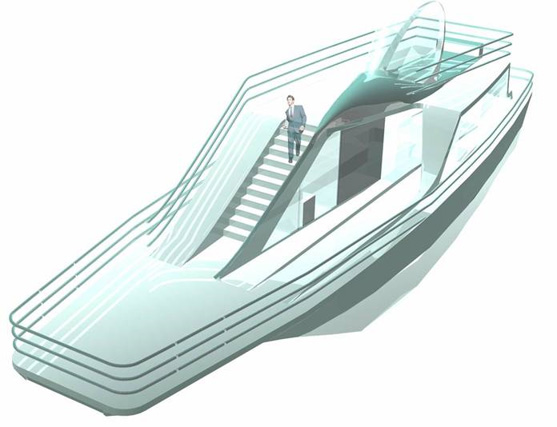

Marie-Theres Deutsch: Definitely! We were invited to take part in a competition to design a mobile opera pavilion for 70 musicians in front of Alte Oper. We won the competition in the second round and were commissioned to handle the implementation planning together with the engineering office Bollinger+Grohmann – it was a brilliant design. ARCH+ magazine published the project, and there was a great response. One week before construction was scheduled to begin, the project was suddenly terminated. I received a call from a secretary in the Municipal Building Dept. who informed us we should down all tools with immediate effect. That was rough. We’d worked on it intensively for two whole years and fell into a deep, dark hole. To this day, I don’t know the reason why the project was discontinued.

The idea for a water-taxi line also did not get realized. To coincide with the FIFA World Cup 2006, the plan was for six water taxis with designs corresponding to the skyline to ply their trade between Westhafen and Osthafen. Friedrich von Metzler, who sadly died a few days ago, really helped me back then to find sponsors for the taxis among riverside residents. Each sponsor would have been responsible for one water taxi and would have had to finance its operations for the first three years. The Nauheimer family was brought on board as operator of the taxi line, and the FPS law office supported us, drawing up the contracts on a pro bono basis.

The very well advertised multimedia SkyArena light show during the World Cup successively promoted the sponsors who had already signed up with immense promises. I had myself financed the Mainlust water taxi, and more than two years of presentations given for free along with meetings and planning adjustments took me to the brink of financial disaster. Petra Roth, at the time Lord Mayor of Frankfurt, promised to support us with everything other than financing. After being informed of that, I announced the end of the project in the Frankfurter Allgemeine. In conversation, people to this day still ask me about the project. The idea remains as good as ever, even if a different financial concept needs to be developed.

Is Frankfurt a city that does not tap its potential, specifically with regard to creativity?

Marie-Theres Deutsch: It is my conviction today that Frankfurt is a city of business and banks. We had a brief culture bubble with Kasper König, when galleries received grants to attract the gallery and art world into the city. It was a brief heyday lasting perhaps 15 years. Patrons such as Sylvia and Friedrich von Metzler really need mentioning in this context as they supported the unconventional ideas, too. You need outstanding individuals to drive cultural ideas if you are to ensure that exciting projects such as, right now, the Frankfurt Prototype (editors’ note: which went on display in October 2024 for three months at the Senckenberg Museum) do not disappear back into the ether after only a few months. Back then, as regards the Portikus, people kept on saying to me: “That tin can isn’t architecture!” The city executive in charge of the Municipal Planning Dept. at the time simply ignored me because I was a young woman. The art box was too audacious for Frankfurt’s high society back then.

And looking back, such a project obviously gets treated with nostalgia.

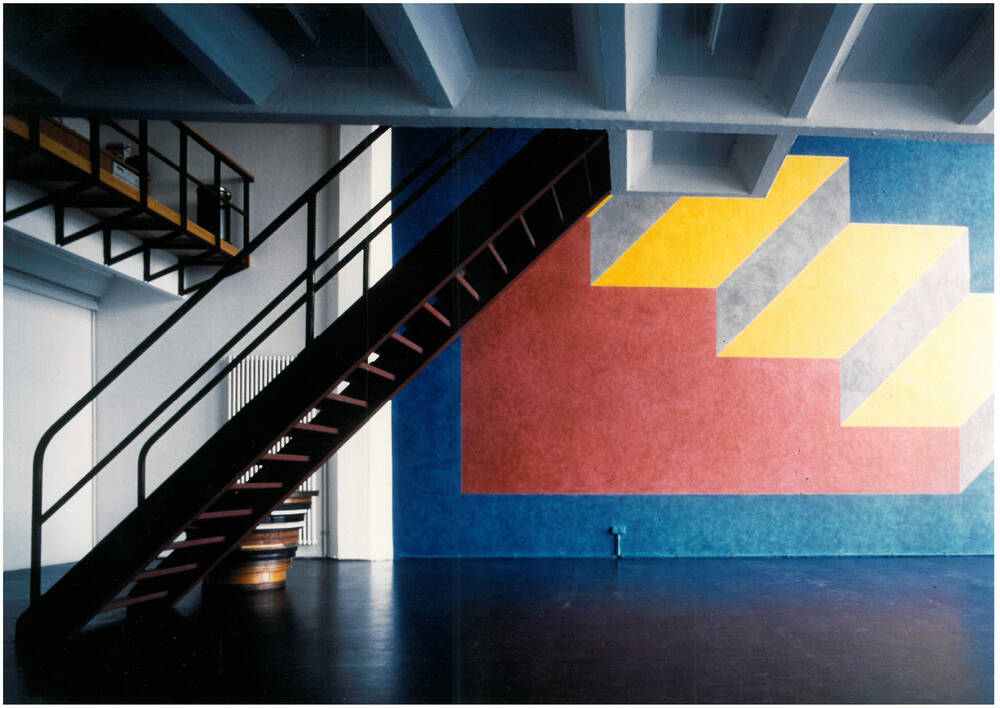

Marie-Theres Deutsch: That has to do with Kasper himself. The myth continues to grow. The glorious exhibitions with avant-garde artists hardly anyone had heard of. And the architecture played a part, too. The building was the antithesis to the riverside museums, as Dieter Bartetzko wrote back in 1987 shortly after it opened. To this day, it remains inconceivable that artists can perforate, convert, extend, or make incisions in a museum building. We performed this service for art in the form of the Portikus. I was able to assist a series of artists, in part making massive interventions in my own building.

What plans do you still want to realize? What are you currently working on?

Marie-Theres Deutsch: There is a project close to my heart and a project to make money. As an architect, you want to pursue both approaches if at all possible. On behalf of an investor, I am currently planning a larger housing project out in Frankfurt’s chic suburbs. In Alt-Sachsenhausen, I have been involved in a project for several years now that was delayed owing to the pandemic and the subsequent phase of high interest rates. At present, I wait with bated breath to see how the municipal authorities respond. There were times when you took a lawyer with you when visiting a municipal department; that did not improve the mood. Gradually, things appear to be changing, and of late I’ve enjoyed friendly and constructive meetings with the local authorities.