The artist Alfred Ullrich has spent a sufficient number of decades in the art world and engaging with it to know that attributions can always change. While his own family history may have been bubbling under the surface of his abstract color etchings for some time it was not until later that Ullrich openly highlighted his biography. In interview he relates how this came about.

Artist? Sinto artist? Viennese or German artist? As Alfred Ullrich once told me, identities are a tricky business. He has spent a sufficient number of decades in the art world and engaging with it, in printer’s workshops, galleries, artist groups and exhibition rooms to know that attributions can always change, as can what is currently the rage. “It’s difficult for me to see myself as an artist,” says the man who is now in his mid-seventies. Ullrich grew up in Vienna as the son of a Sinti woman, who survived the Third Reich. He had a beautiful childhood in a covered wagon and in the hay but always on the fringes of Austrian society. And though his own family history may have been bubbling under the surface of his abstract color etchings for some time it was not until later that Alfred Ullrich openly highlighted his biography.

Mr. Ullrich, you were a grocer, typesetter, postal worker, worked in bronze casting and as a stagehand for theaters in Munich …

Alfred Ullrich: And a lot more besides!

…and then in your late twenties you became an artist, or let’s say you discovered printmaking. How did that come about?

Alfred Ullrich: That was around 1976 – after a few years of wandering around Europe aimlessly, and when the German authorities no longer had me registered for military service – how old would I have been? Maybe 28. I had been in Bavaria for some time. I am actually Viennese, you know. When I needed an ID card as a young man, I was practically drafted for military service at the same time. The nature of my family circumstances actually helped me: Although my mother had only been married to my German father for two years, I was able to apply for German citizenship. No way did I want to do military service with superiors who had been actively involved in the Third Reich – I couldn’t bear the thought . And as a 14-year-old I couldn’t think of anything other than applying for German citizenship. Which meant that from then onwards in the city I had grown up in I had to regularly go to the police as a “foreigner”. It was a weird situation. Thus it was that at some point I moved to Munich as a German citizen, and worked among other things in a printer’s workshop. For the Czech Josef Werner, who himself produced a lot of prints for other people. I learned a lot back then and really enjoyed working with color etchings. Nevertheless, at some stage things felt too constricting for me in the family business …later I found a house in Dachau and was able to set up my own copper plate etching workshop. Then gradually I not only did a lot of work for other artists, but also began my own works. Back then it was still possible to put your portfolio under your arm and do the rounds of the Munich galleries – and sometimes they exhibited the one or other of your works.

You were born 1948 in Bavaria, then grew up in Vienna - the son of a Sinti mother, a single parent. Many members of your family were murdered during the Third Reich, including your older brother, yet your own biography was not reflected in your work until later. Were you worried about incorporating too much of your identity into your work?

Alfred Ullrich: Yes, I only really became aware of my biography when I moved into this house in the Dachau district. This old Roman street, I would walk past the former concentration camp every day. At the time I thought: So, actually I know everything through my surviving relatives, I don’t need to look at it. Only later did I find out that three of my uncles had been imprisoned in this camp.

Then again, I had to settle in. It was interesting for me to see what artists get up to, what this cultivated, middle-class life is like and what standing art has in it. I didn’t find that out until then. After all, my life had been completely different.

Yet there was this political awareness. In the mid-1980s the so-called “Group D” was founded in Dachau, which campaigned for a memorial and meeting place at the former concentration camp . Now and then I myself traveled with “Group D”; for example, we were invited to exhibit in France by a onetime Resistance fighter. And we were invited to Vermont or to the Auschwitz Youth Meeting Center. Back then the past was more or less suppressed – in the 1960s, there were even plans to demolish the entire site. There is said to have been a politician who claimed he would oppose such a meeting place “to the last drop of blood” [the Chair of the CSU group on the City Council, Manfred Probst, editor’s note.] It’s interesting how politicians responded at the time – now it’s called Max-Mannheimer-Haus and is a study center that is used for educational purposes and as a meeting place, a memorial site and youth hostel.

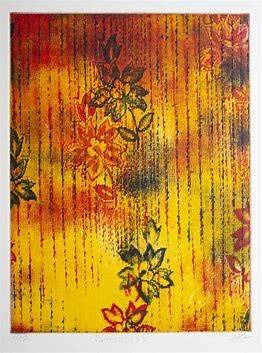

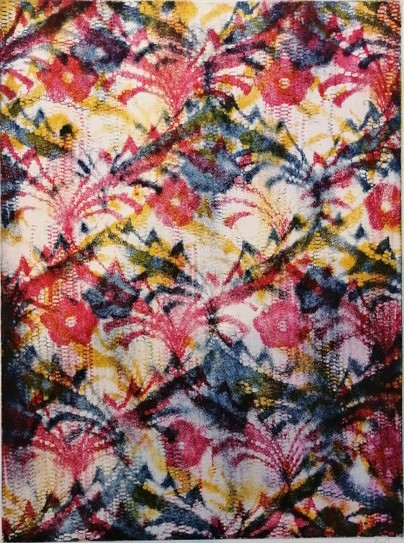

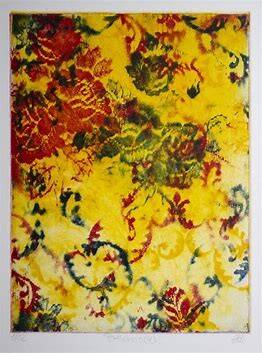

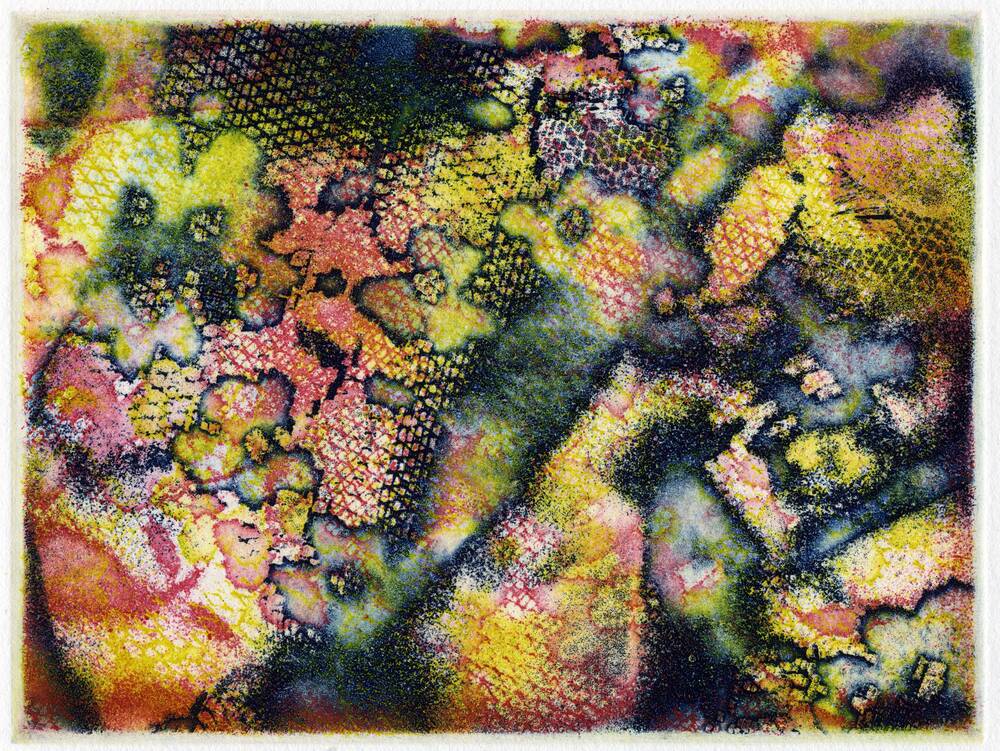

Let’s stay on the topic of printing for a while: You have produced very different works – highly-colorful abstract pieces which remind you of your mother’s bright clothing, but also prints of Ottakringer beer cans, soot from a flame on painting cardboard … How do you develop your work? Is it a kind of reflection, an active mulling over things while working, or do you have a conceptual approach?

Alfred Ullrich: Actually I learned a lot of things without reading any “recipe books”, simply by trying things out for myself, working on my own, and then I often discovered that this or that method had already been used by artists decades ago. Somehow, certain things just suggest themselves when you’re working with etching.

I was self-taught and therefore didn’t have a classical training as an illustrator and usually started spontaneously. That spontaneous beginning, this etching inspired me to continue. However, this also means I might have been planning to produce the atmosphere of a morning, but my experimentation turned it into more of an evening mood (laughs). Now I have a lot of my own techniques that I can work with. That’s good, because I am still far too restless to spend hours, day or months on end sitting and drawing, for example.

Later you realized video pieces and actions. Only then does that topic, your suppressed childhood become more virulent both in society but also for you as an artist.

Alfred Ullrich: Right, with the help of friends who are much better acquainted with the technology than I am because I realized that I couldn’t do justice to the topic with abstract etchings alone. These actions or videos like “Landfahrerplatz, kein Gewerbe” (Traveling Folk Site, No Trading) allowed me to question something through performance because I recognized that without provocation nothing changes in society.

Interestingly enough, it was also through initiatives like that of “Group D” that the more open-minded people came “out from under cover” – and visited and even endorsed these exhibitions. A certain change has taken place. And it was also something of a relief for me to “acknowledge” my identity as it were. After all, I often realized, for example when swapping ideas with fellow artists, that I have a completely different view of things. With the artist actions I was able to become more candid but without attacking anyone personally. That was always an important aspect for me. It was more that I wanted to push politicians into taking a stance.

And how did the art world respond back then? After all, you introduced topics and facts that were not only suppressed by society as a whole, but that were also largely considered taboo.

Alfred Ullrich: By then I had already been known as for my prints for a good 20 years. My solo exhibitions were always attended by a lot of really interesting people. They also came to these exhibitions and really engaged with my art. For example, in the Neue Galerie Dachau I once installed a sofa, a little table, some small dishes with nuts, but then the television showed a video that my sister had made with my mother where she talks about her time in the concentration camp. It was very moving because she often had to stop, couldn’t go on speaking.

I just remembered something my mother often used to say: “The Gadji, watch out, watch out, the Gadji – that’s what she called the Germans - they steal!” Interestingly enough, this is exactly how the majority of society still views the Sinti and Roma. Today, I think I know what she meant. The concentration camps and the raids confirmed who the real thieves and robbers are.

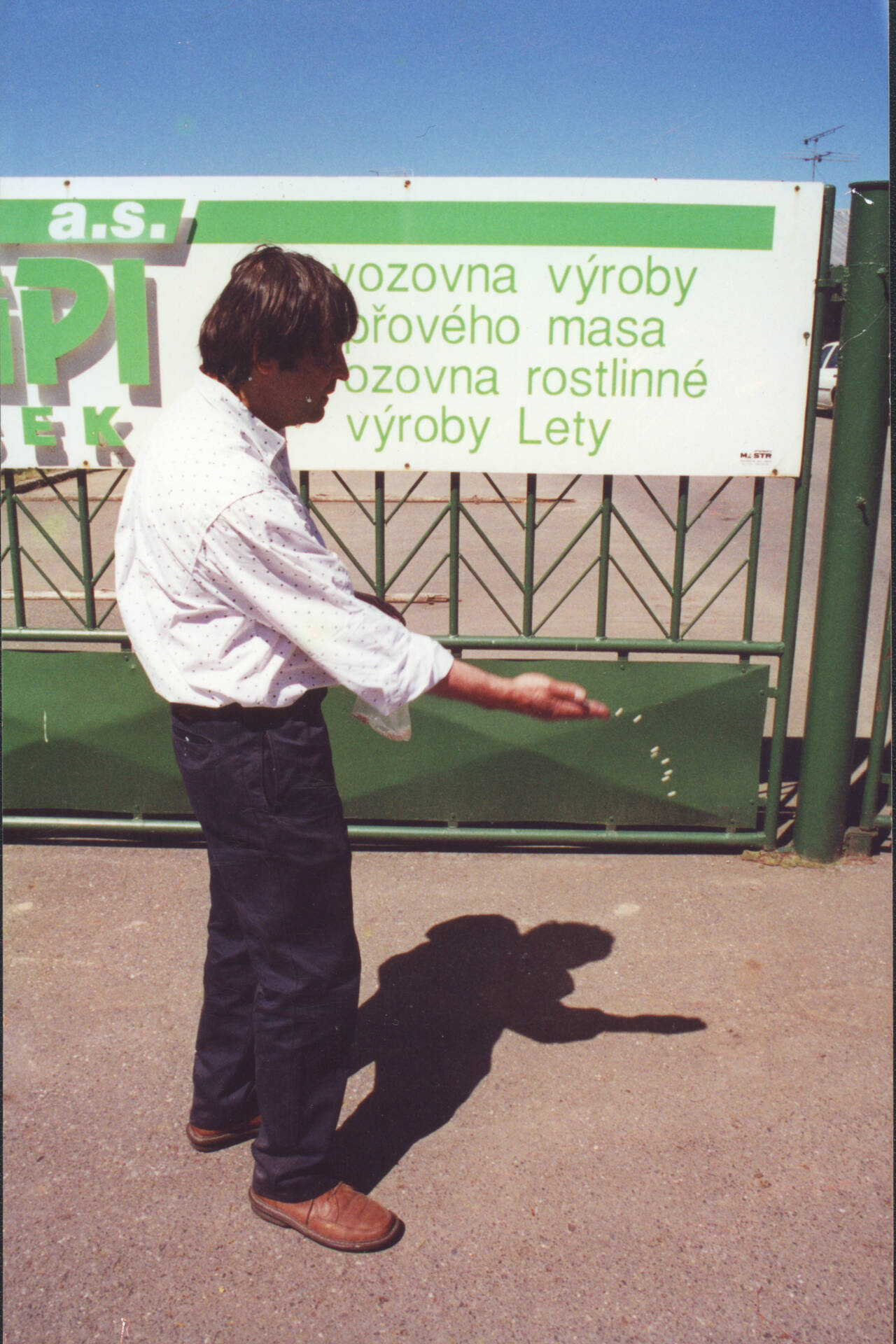

In 2000, you realized the “Perlen vor die Säue” (Pearls before Swine) action in Lety, in the Czech Republic. From the 1970s until 2018, a pig farm was located on the site of the former concentration camp where mainly Roma were imprisoned. Your sister gave you the beads from her necklace which you then threw in front of the entrance gate in a performative action. Didn’t they later show a documentation of the action in Venice?

Alfred Ullrich: Yes, I think that was 2011. Later the site was acquired by the Czech state, and in 2022 the pig farm was finally torn down. [Jana Horváthová, Director of the Museum for Roma Culture, stated that the fact that a memorial was erected here, the demolition, marked a “turning point”. The current Minister of Culture Martin Baxa apologized for the numerous politicians who for decades had ignored this aspect of the country’s history, editor’s note.] I am now being shown again in a group exhibition at the Biennale. On arriving in Vencie by train, that was mid-April, a group of thieves robbed me. My money was stolen, my cards. When I reported it to the carabinieri I had to fill out a form and one of the questions on it was: “Can you remember: Were they Arabs or were they gypsies?” They actually still ask that today. Then I felt quite different about this exhibition – because this year’s world art show presents itself as being very concerned. A consternation that is almost difficult to take, given that simultaneously the state that provides space for this cultural event issues such forms in 2024. I don’t imagine anything like that would be tolerated in Germany.

Naturally, that makes me wonder what importance art can have at all. This biennale has been held for 100 years and then to have a slogan like this year’s motto – is it all just for show? And if so, for whom? Way too many tourists visit Venice as it is …and there’s a certain irony in something like that happening to me of all people.

You are currently working on etchings about the naval battle of Lepanto, and the latter also has a certain connection with Venice and antiziganism.

Alfred Ullrich: I am producing it for the exhibition in January in Berlin. As it was a naval battle and everything plays out at sea I didn’t want to get too specific. I cite the history of this place: The Spanish king had declared the Gitanos, the Roma living there at the time, to be outlaws – and they were then deployed in the galleys against the Turks. Conversely, the Turkish rulers also used the Roma as “oar slaves”. That was what motivated me to create these works, the realization that this discrimination has persisted for centuries in many different variations. And it continues to this day. I didn’t finish the works on time, but the exhibition will later move from Venice to Berlin and I will show them there.

You have already been in the art business for almost 45 years. How do you rate your role there today?

Alfred Ullrich: I suppose on the one hand I am integrated, if you like, but then again, I often still have the view of an outsider looking in. Although I am intrinsic to the system. I guess that gives me an advantage being able to do that but simultaneously looking at things from the outside. That said, I would like my artworks to function for themselves without presenting anything activist or ideological. That’s important to me.

It’s difficult for me to see myself as an artist. You see, prints were something that I could put between myself and society. That meant I could avoid talking about the issues that really concern me. These old curtains that my mother used to sell as a hawker, and I often accompanied her, and which are the basis for many works: These curtains often hang as a veil between perception – between what happened and how the descendants of the perpetrators like to portray it today. These are the curtains that hang between and which I feel prevent an authentic conversation, a real reflection.