NEW APPROACH TO MIRÓ

You are familiar with Joan Miró as one of the greatest 20th century artists, with his imaginative visual worlds and powerful colors. But do you also know his large formats? Are you aware of his fascination with walls, both inside and outside? Of his experiments with unusual materials? The SCHIRN exhibition PAINTING WALLS, PAINTING WORLDS gives you an opportunity to discover a side to Miró that previously was scarcely known – about 50 in some cases monumental works from important museums and private collections all over the world.

I want to assassinate painting.

Joan Miró

A murderer and his motive

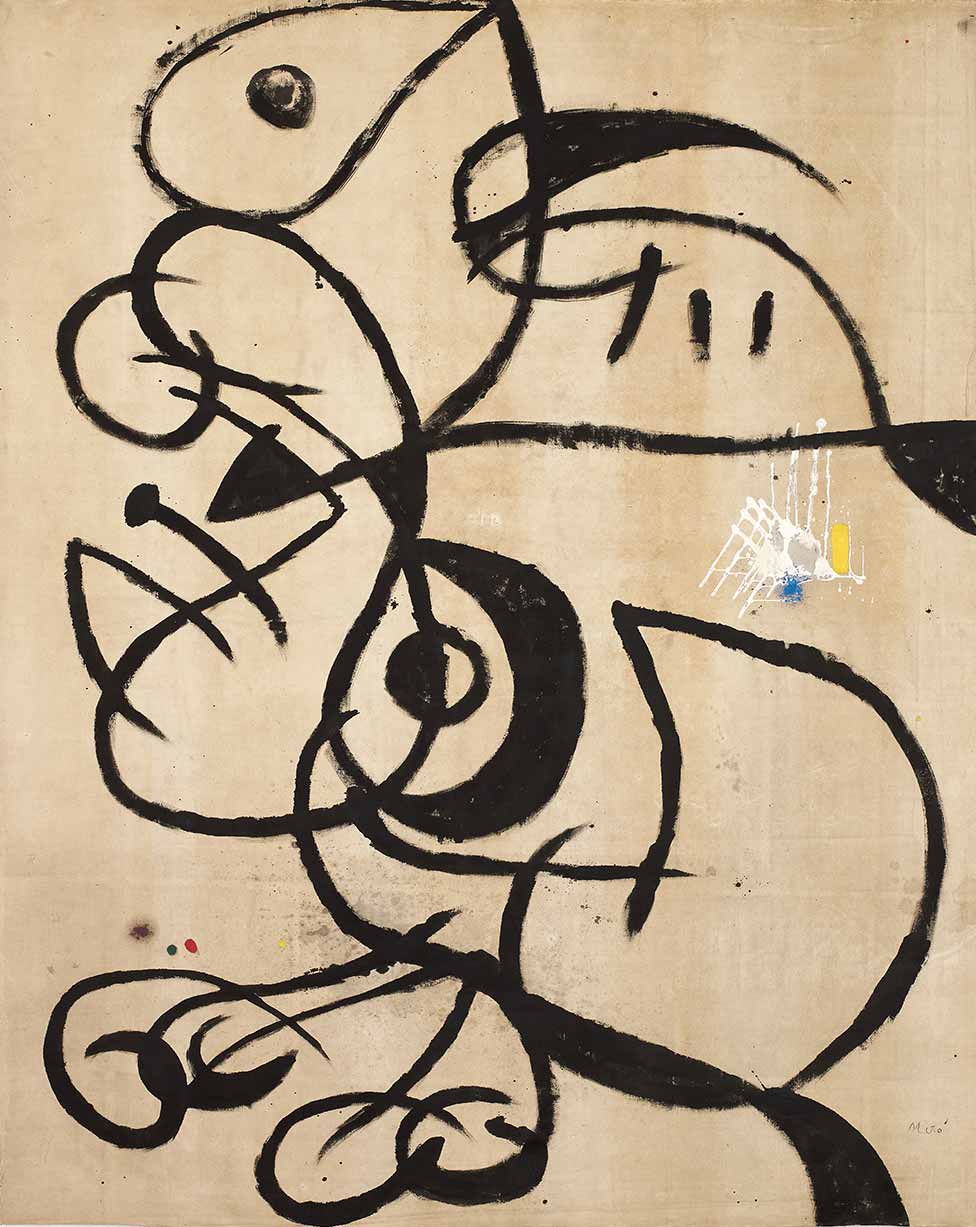

At an early date Joan Miró developed the wish to put an end to conventional painting. In 1927 the always perfectly clad young man announced in public: “I want to assassinate painting.” The public was incensed, until it became clear what his motivation was.

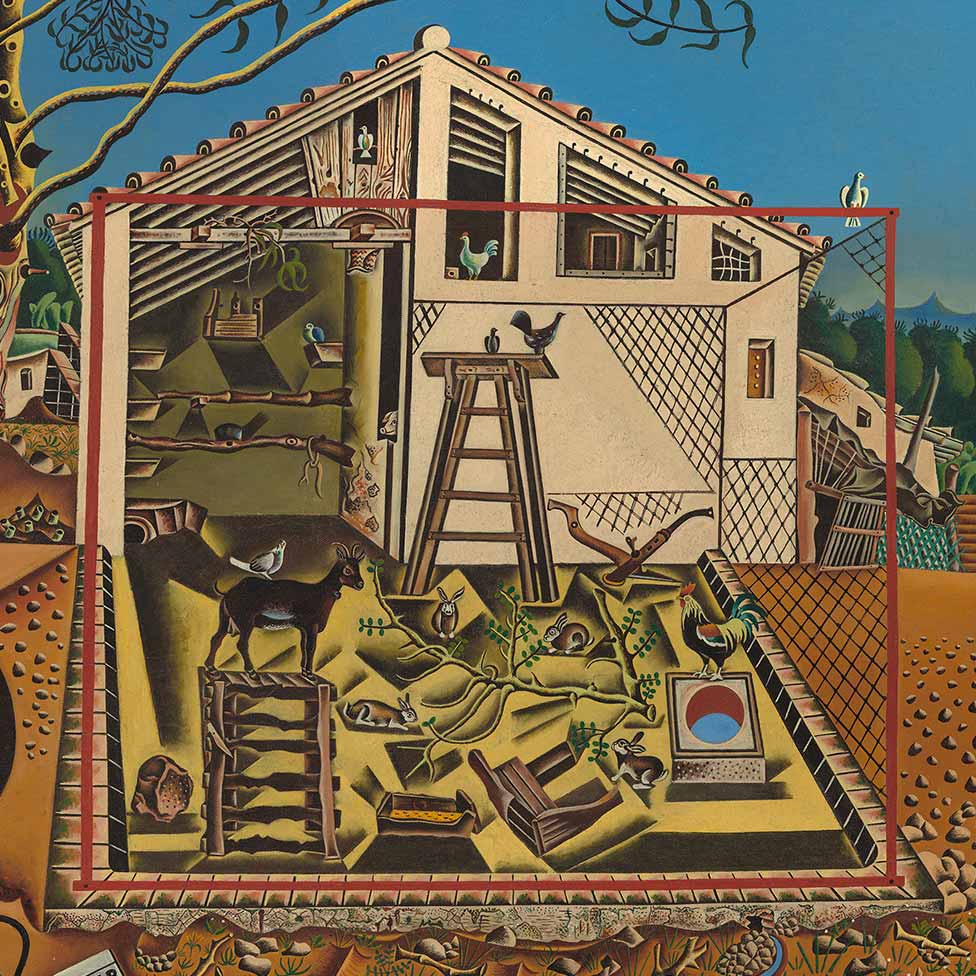

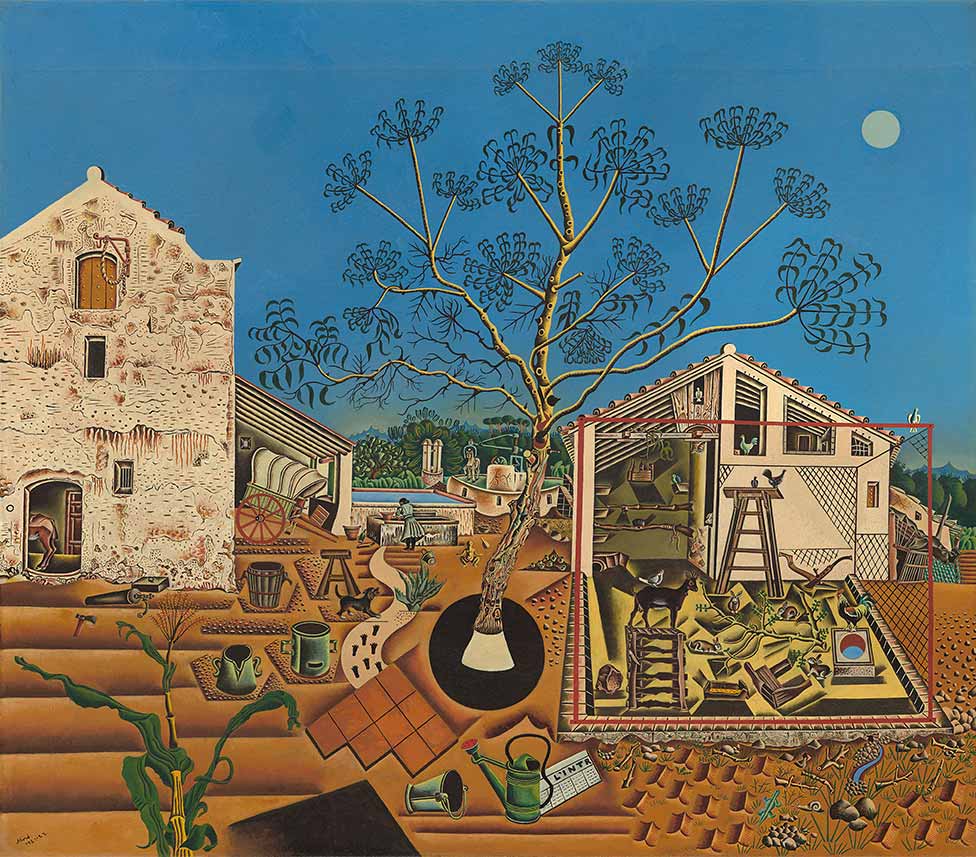

The entire world in a single image

Unlike his Surrealist companions, Miró found it easy to forgo life in the pulsating metropolis of Paris.

The magic of the primordial

A poetic vision

Head over heels into the world of symbols

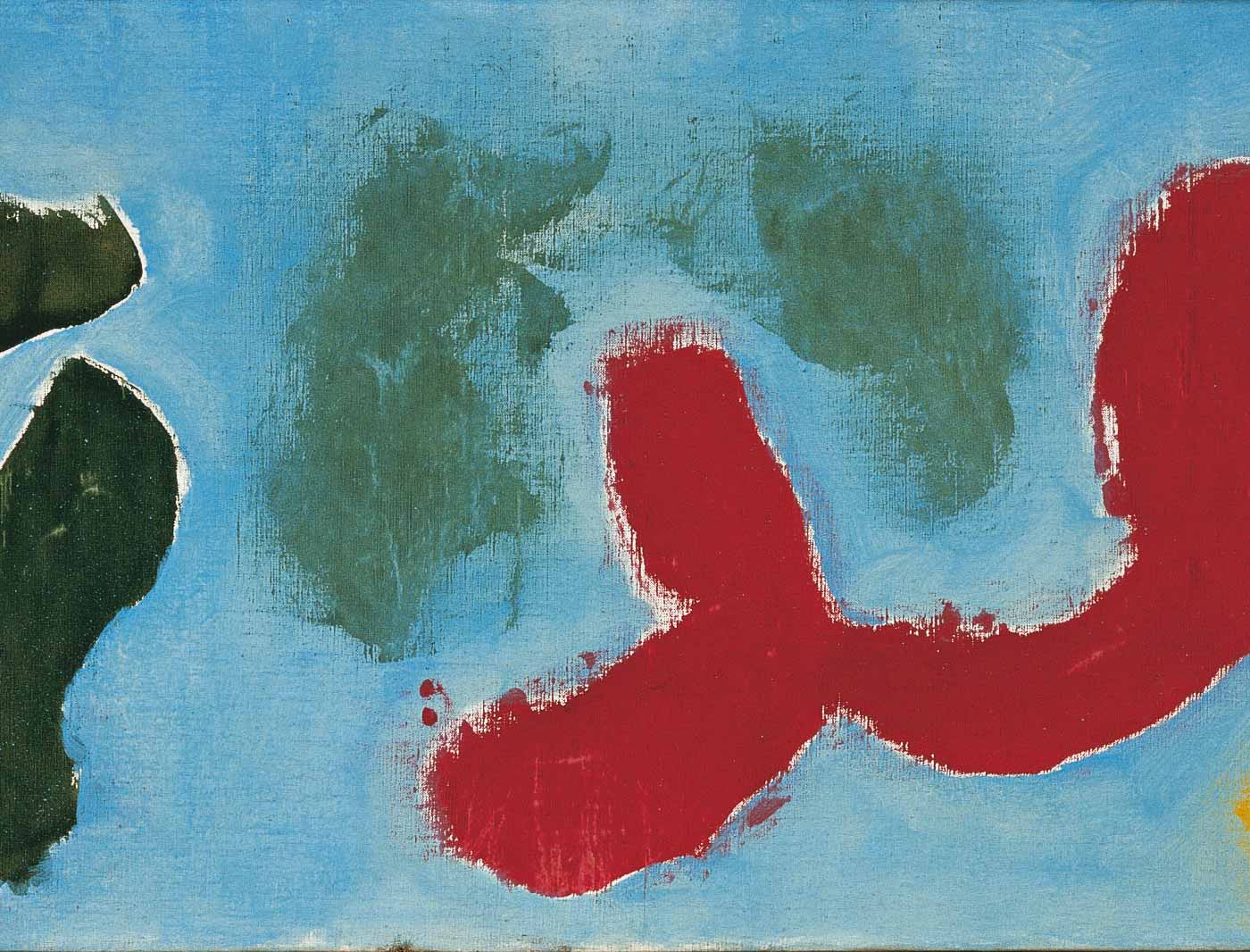

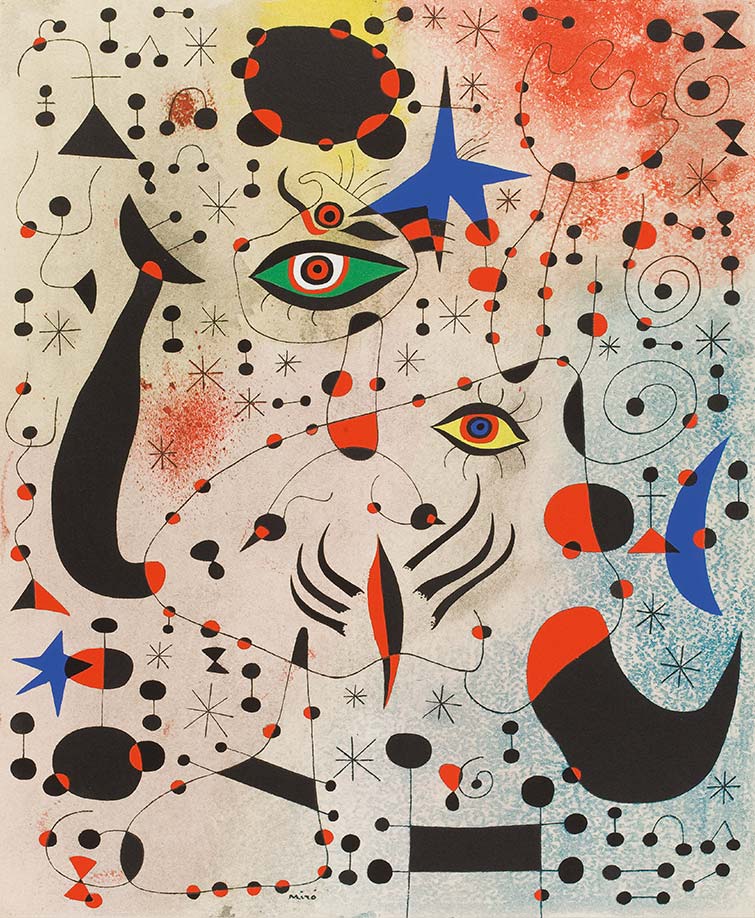

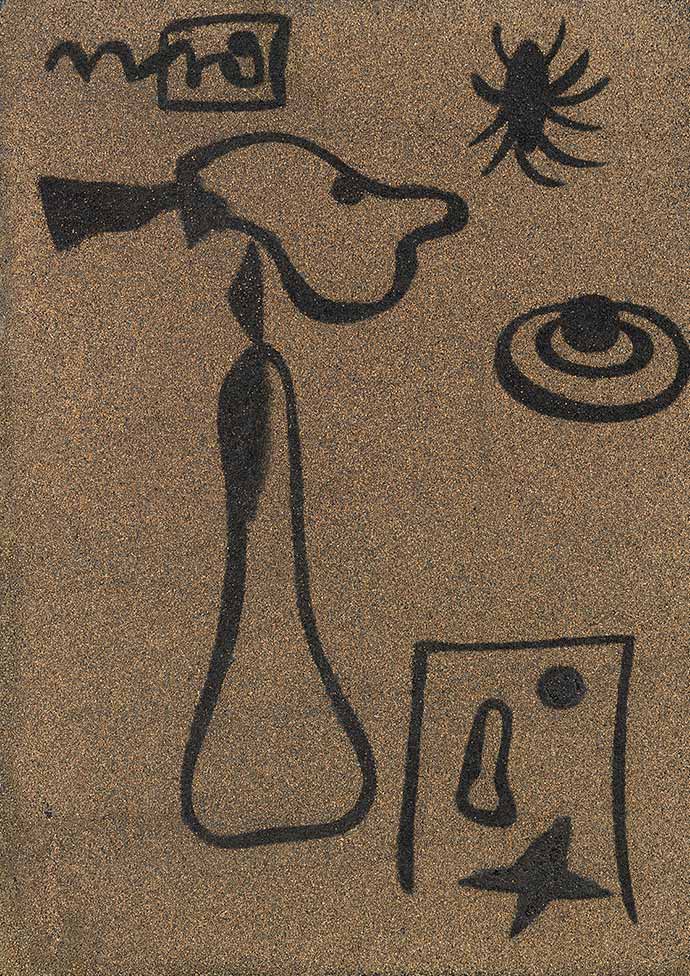

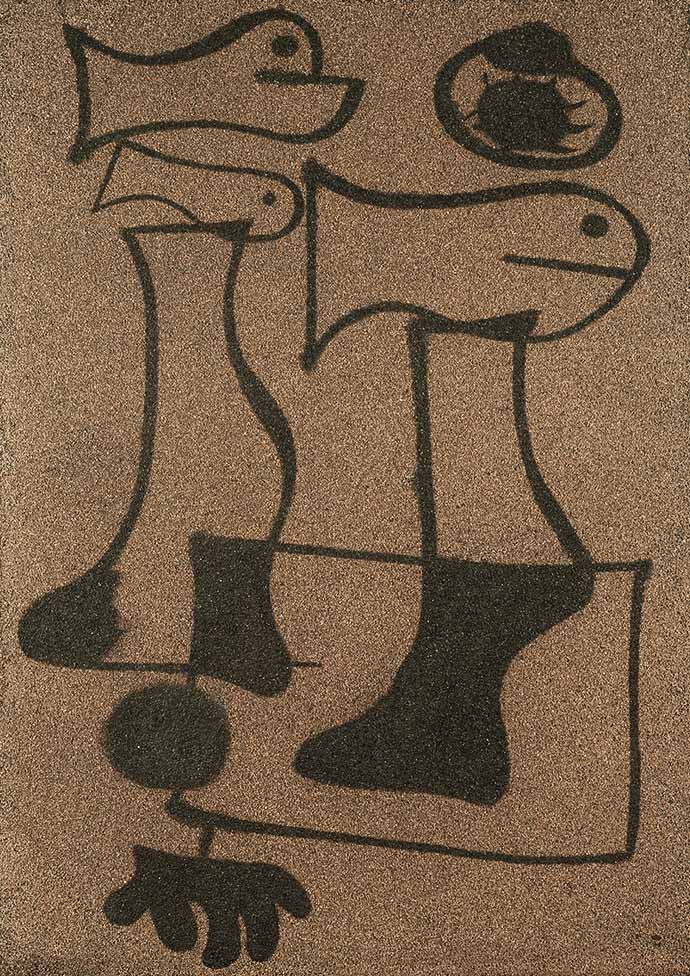

As early as the 1920s, Miró continued to advance his own language of images and symbols. Elements already hintend in “The Farm” were developed quite radically a few years later.

From 1926 onwards Miró regularly changed homes, moving between Paris, Mont-roig and Barcelona. Cultural, domestic and political upheavals as well as aspirations for regional autonomy shaped the face of Spanish society during this epoch. With the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936 Miró first withdrew to Mont-roig, where he started working on Masonite woodchip panels, and then he went back to Paris.

New old worlds of images

A balmy summer’s night

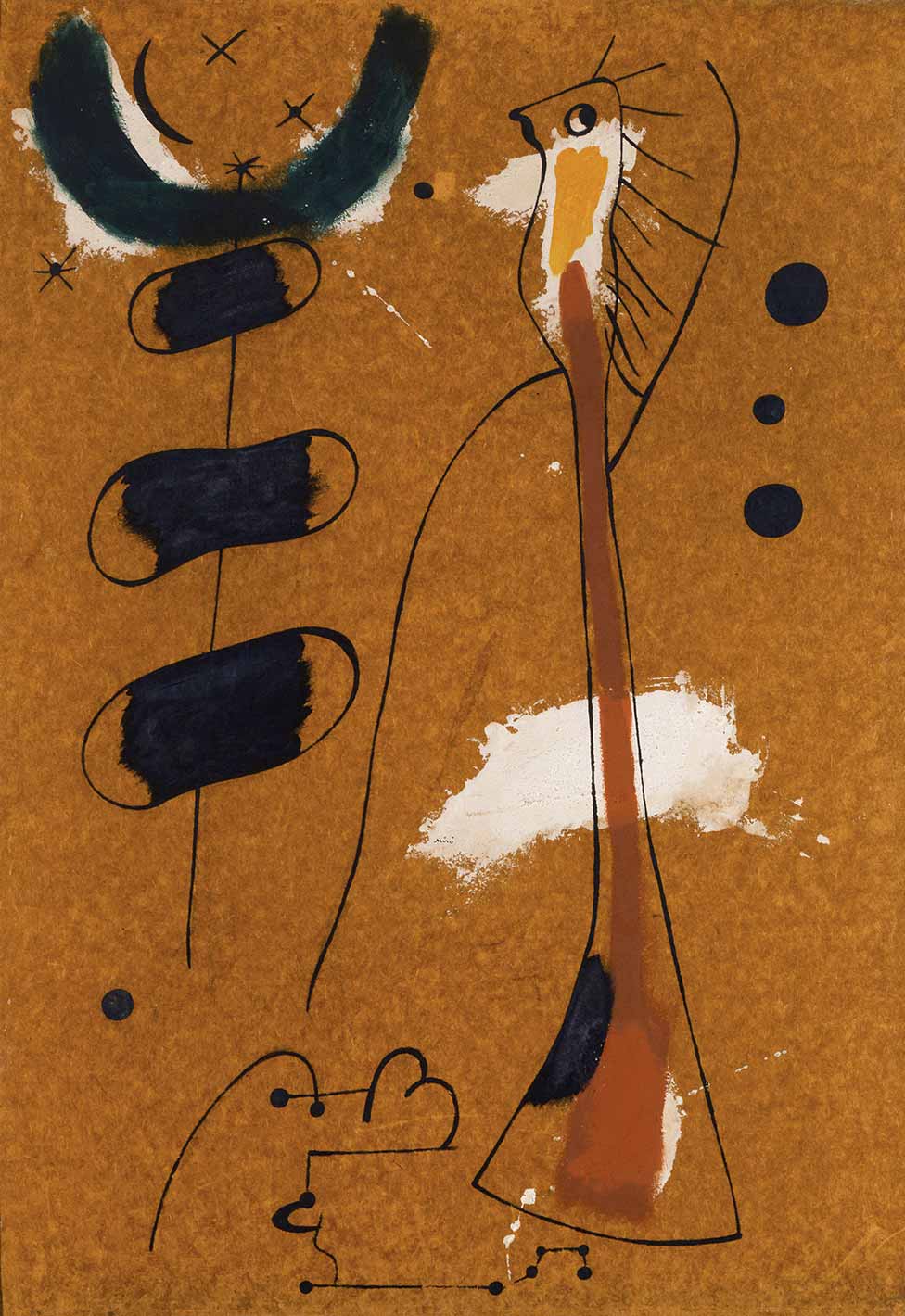

Timeless symbols of rural life

With a few lines, Miró sketches a Catalan farmer in his peasant garb.

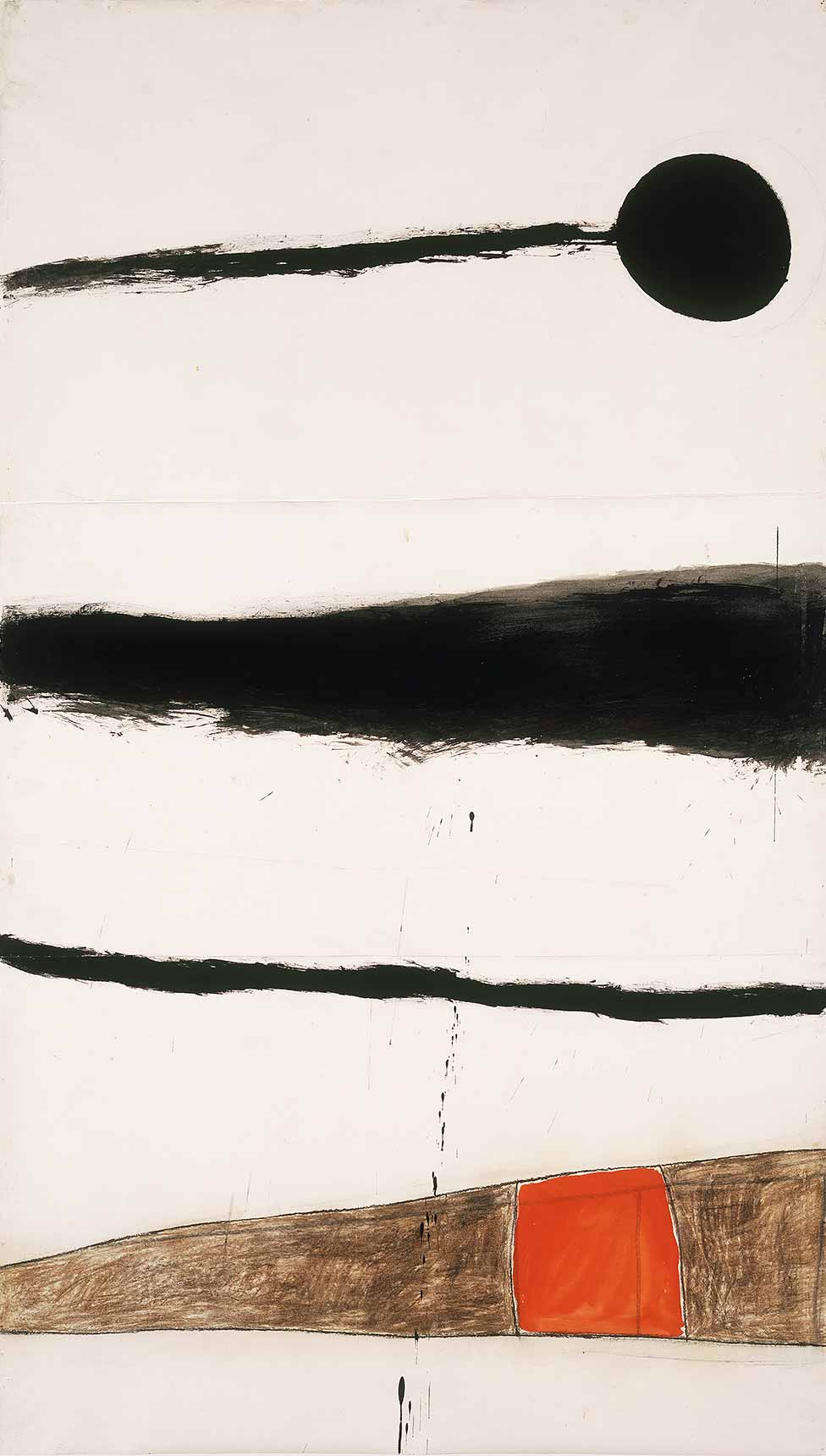

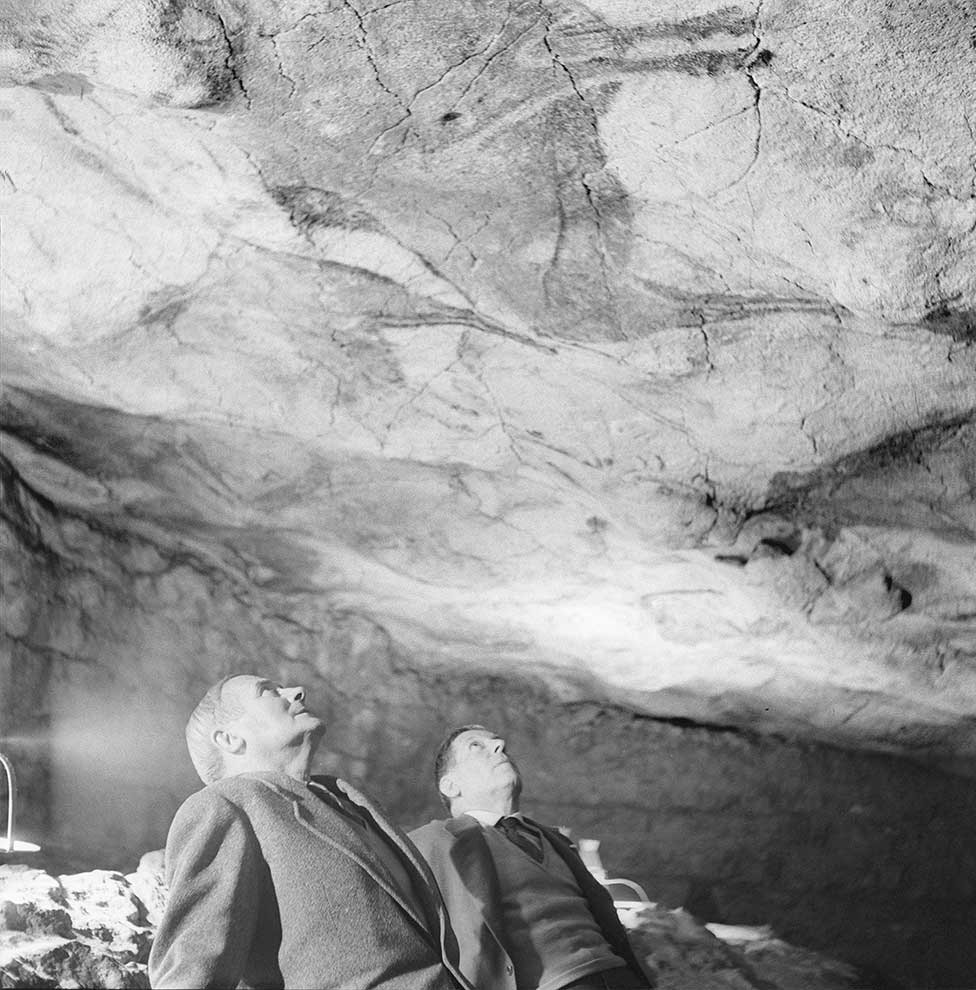

Thematically speaking, Miró remains faithful to his rural roots. Recurrent symbols for plants, human and animal figures or constellations of stars are universal and timeless. They form the core of a symbolic language that highlights primordial human experiences, the simplicity of which is already to be senses in cave paintings.

A painter shows his colors

The painting “Spanish Flag” (1925) expresses Miró’s patriotism.

Twixt Heaven and Earth

The world of the imagination

I withdrew into myself and the more skeptical I became of my surroundings, the closer I came to all those places where spirits dwell: trees, mountains, friendship.

Joan Miró

The Meaning of Colors

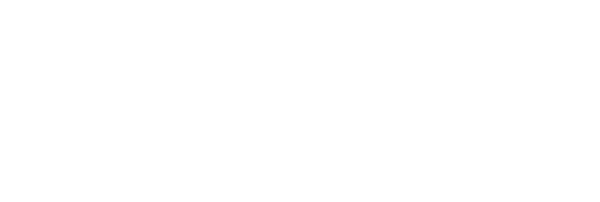

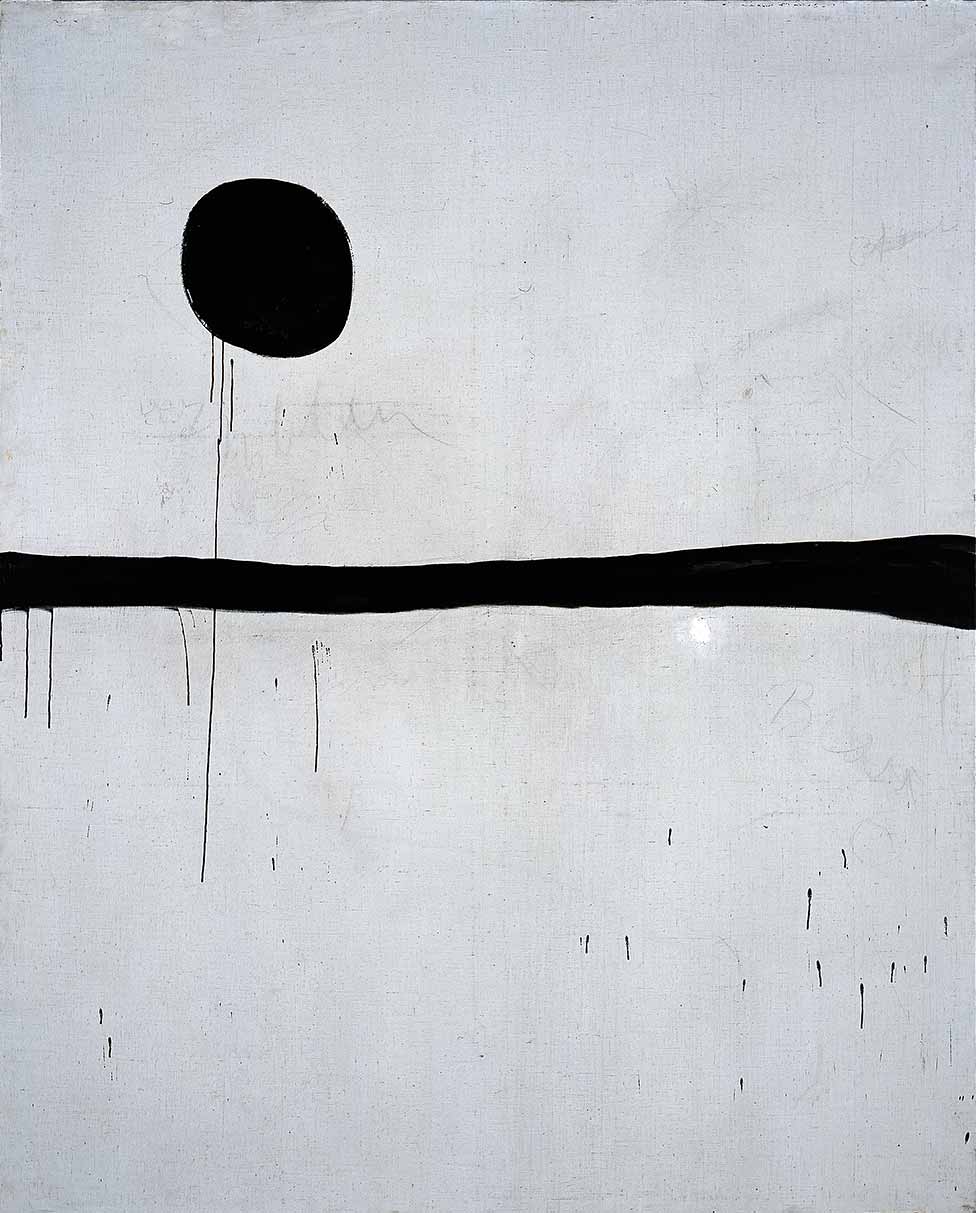

Radical reduction

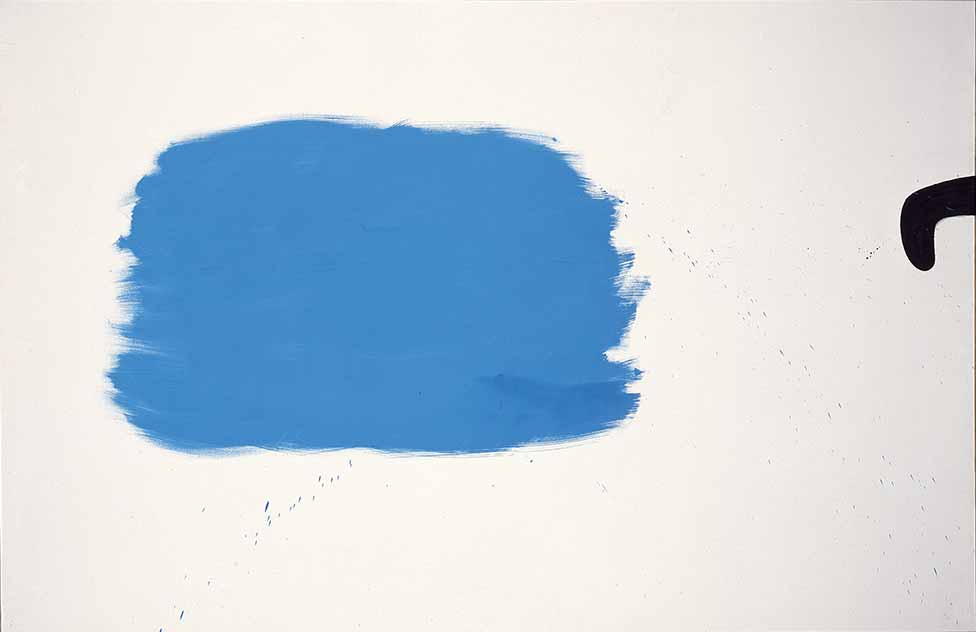

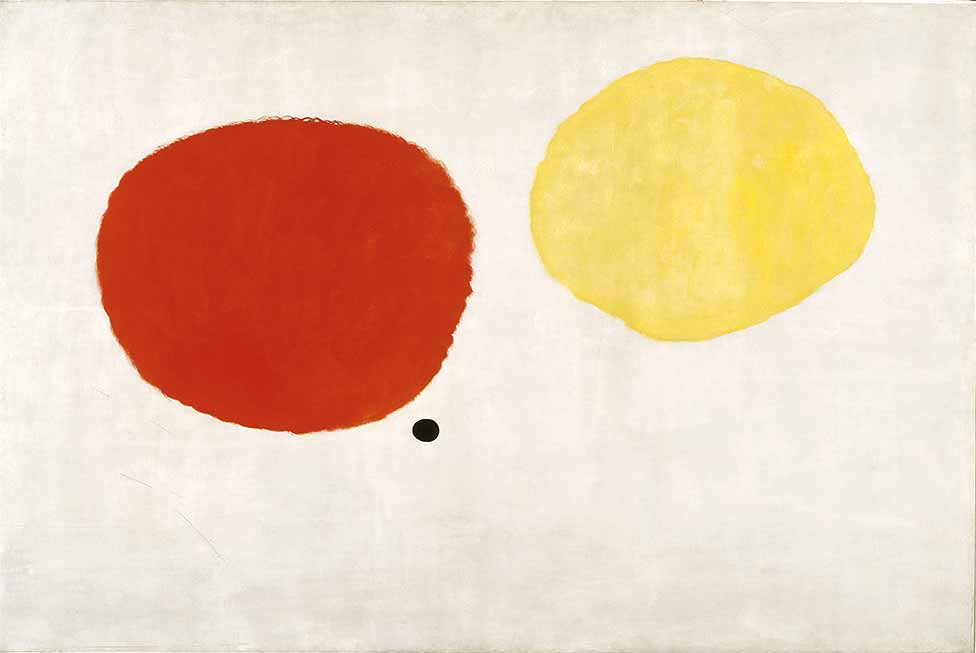

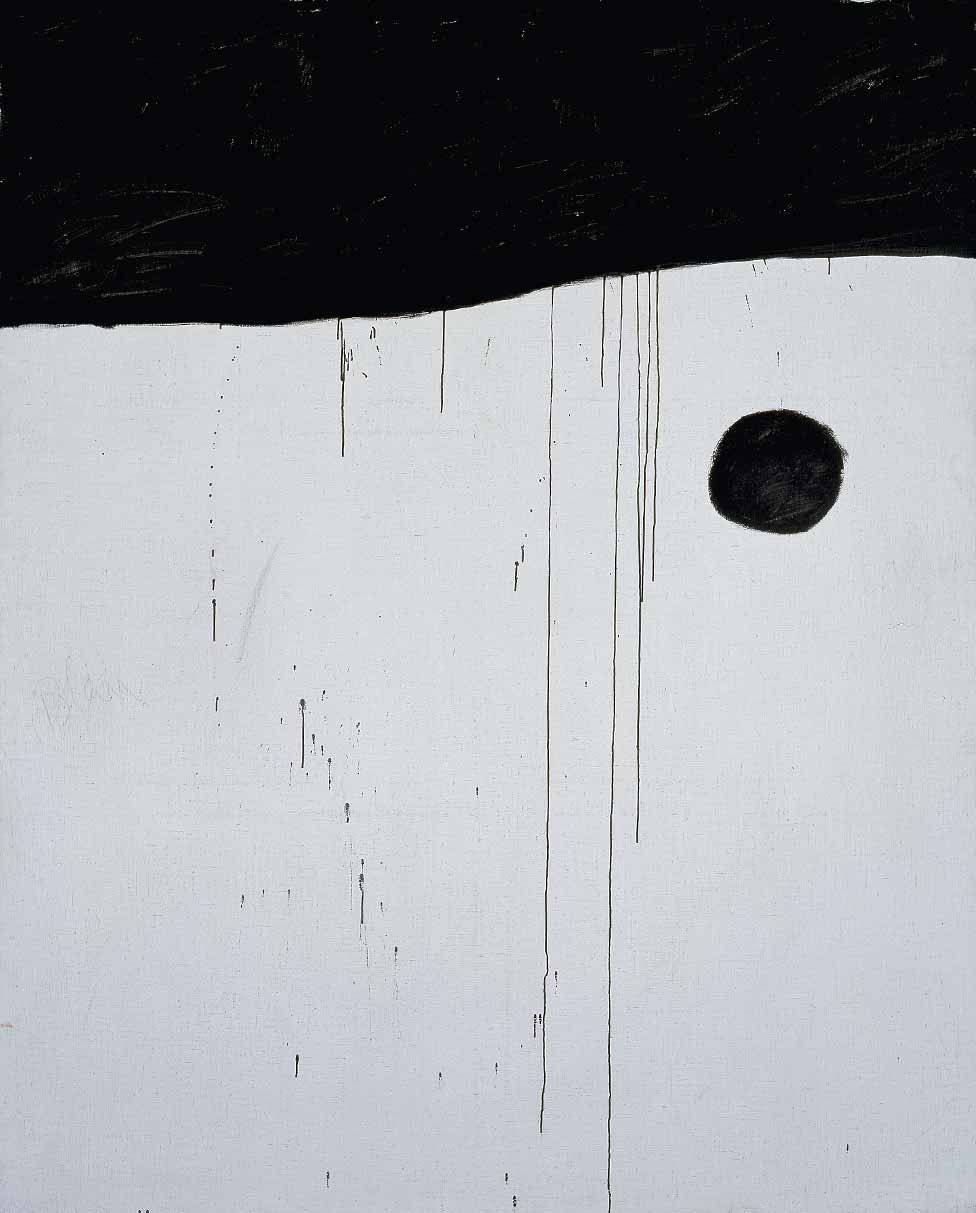

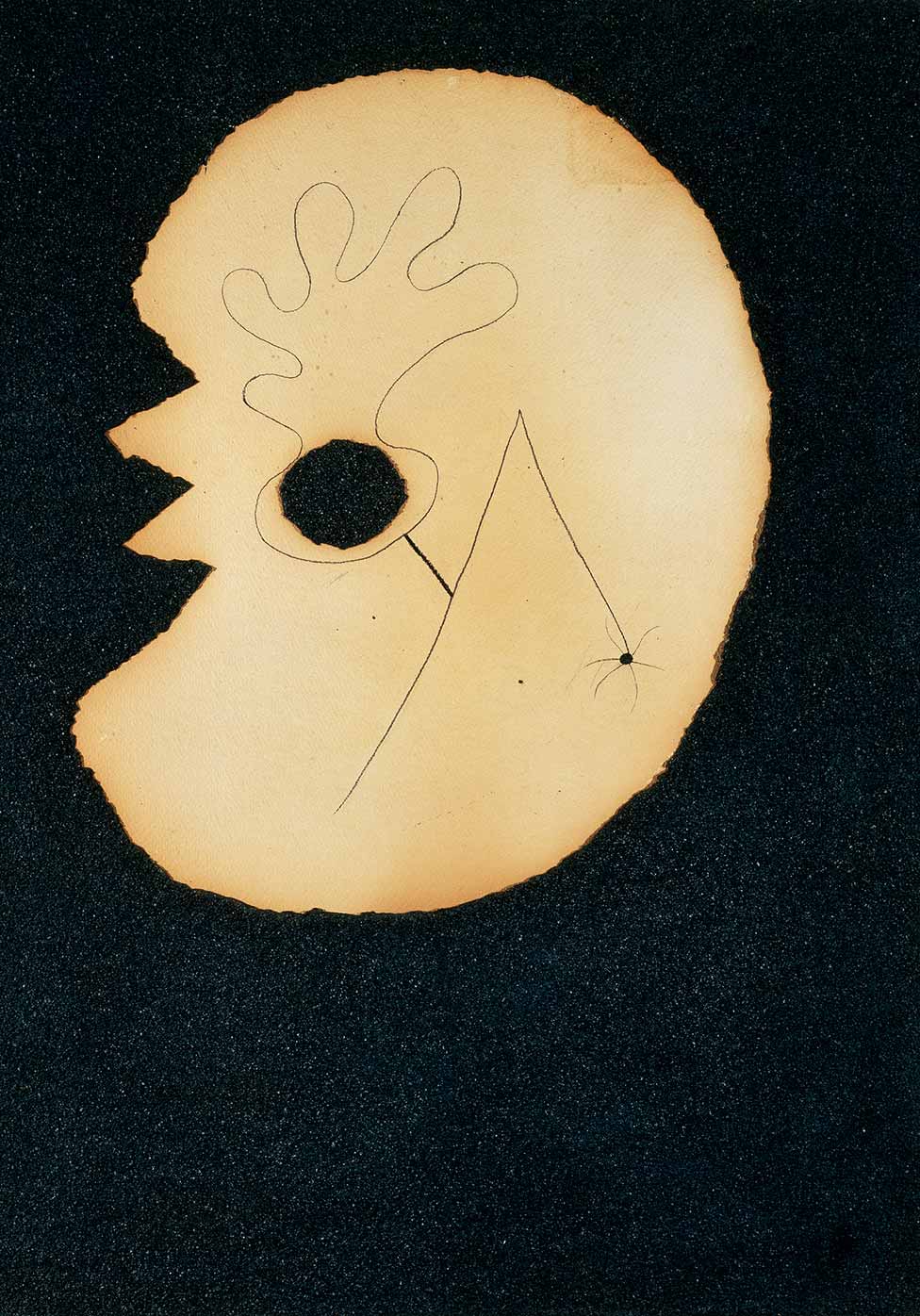

A white grounding. Two large patches of color, one yellow, one red. A small black patch. And nothing else?

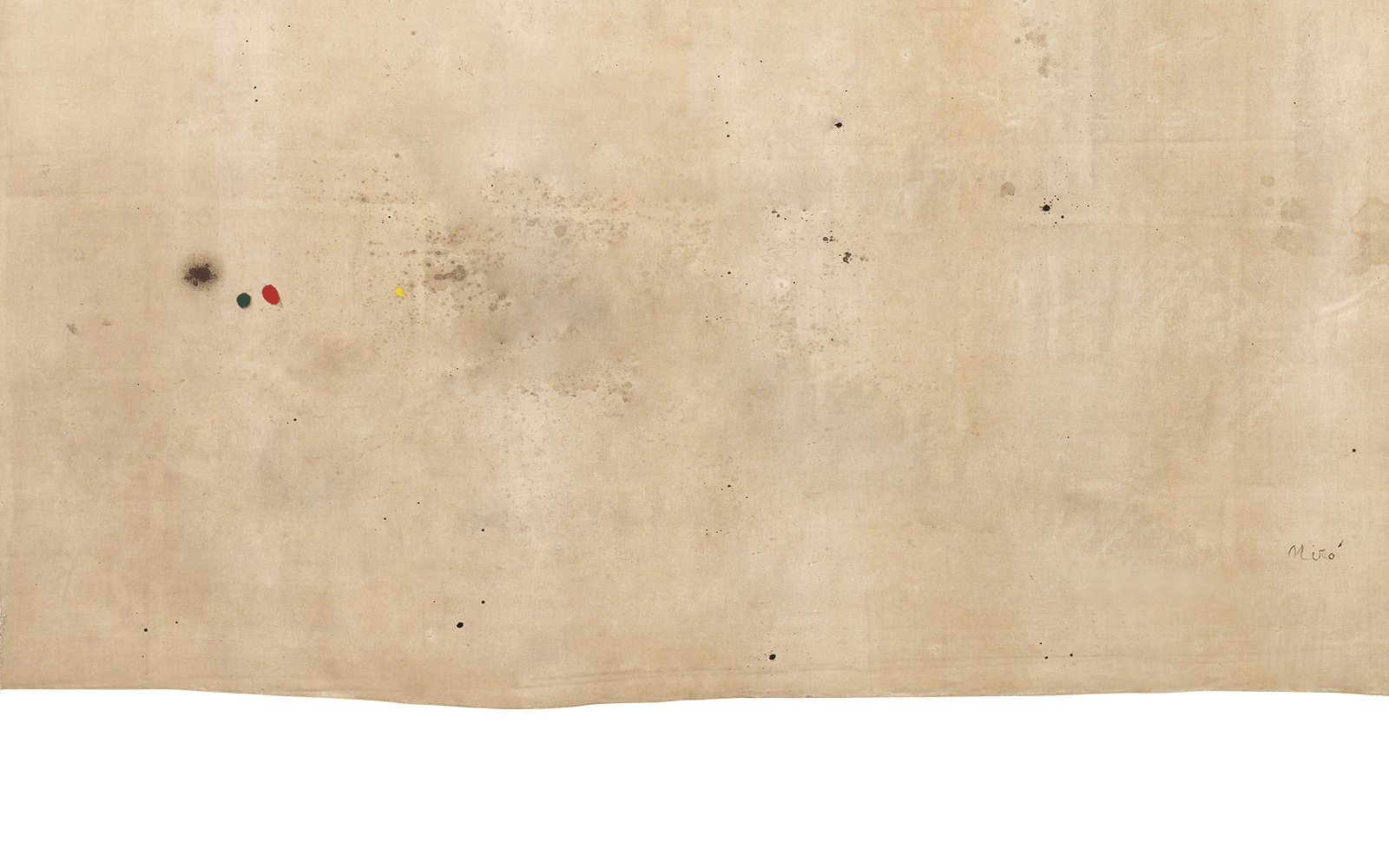

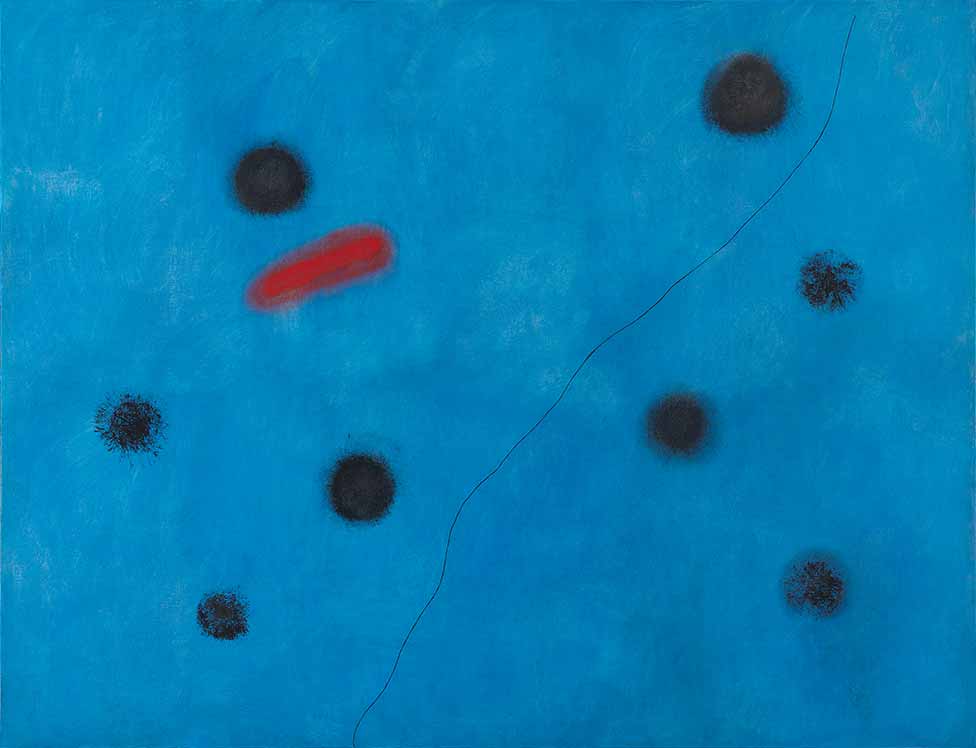

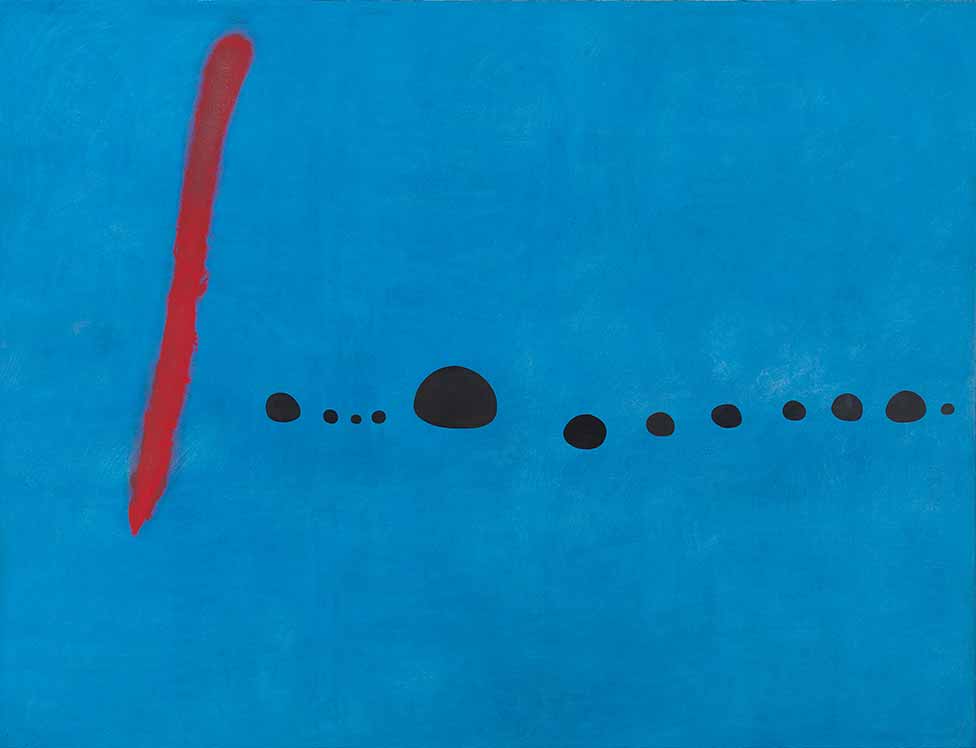

Limitless Blue

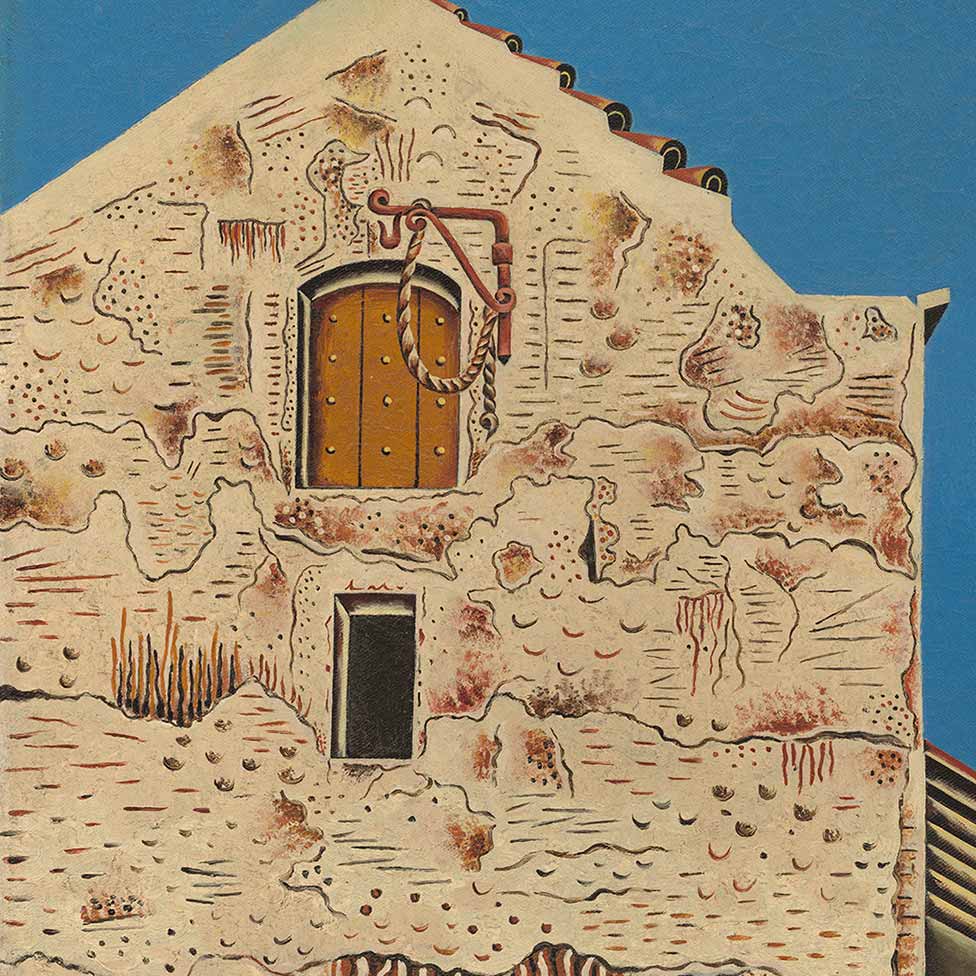

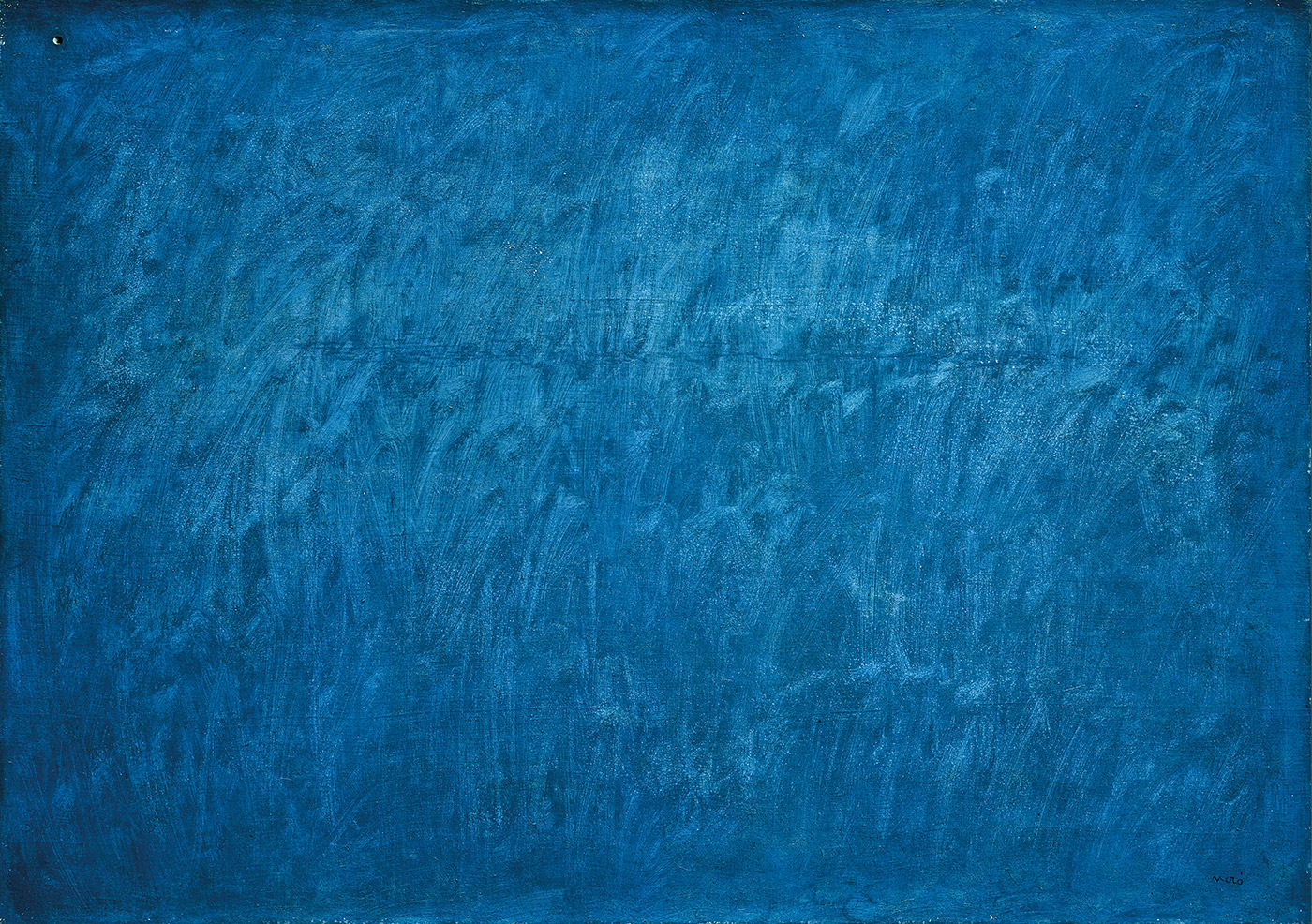

An old Mallorquin proverb seems to have been translated into art in the painting simply entitled “Blue”: “It was and it was not.” But is there anything here? Miró has simply dyed the entire surface blue! Not evenly, but with clearly discernible brushstrokes.

One invariably thinks of the sky when seeing a large blue surface. On closer inspection, however, it turns out to have a small error: In the upper left corner there is a small dot, an intentional irritation! In the form of this patch Miró is thinking beyond the confines of traditional painting by alluding to the destruction of the grounding as a creative element in the pictorial space. A hole would expand the flat medium of the painting into the third dimension. This small detail seems, as it were, to pre-empt the works of Lucio Fontana who in the mid-20th century revolutionized the concept of space in painting by actually carefully destroying the medium of the canvas. The reduction of colors is later echoed in the works of an Yves Klein or a Mark Rothko.

If one looks more closely, one can make out a horizontal change in the picture’s surface in the upper third of it. It is almost as if the canvas had had a tear here that someone tried to repair with plaster, as one would do with the wall of a house. Here too, Miró’s works reference walls as a source of inspiration.

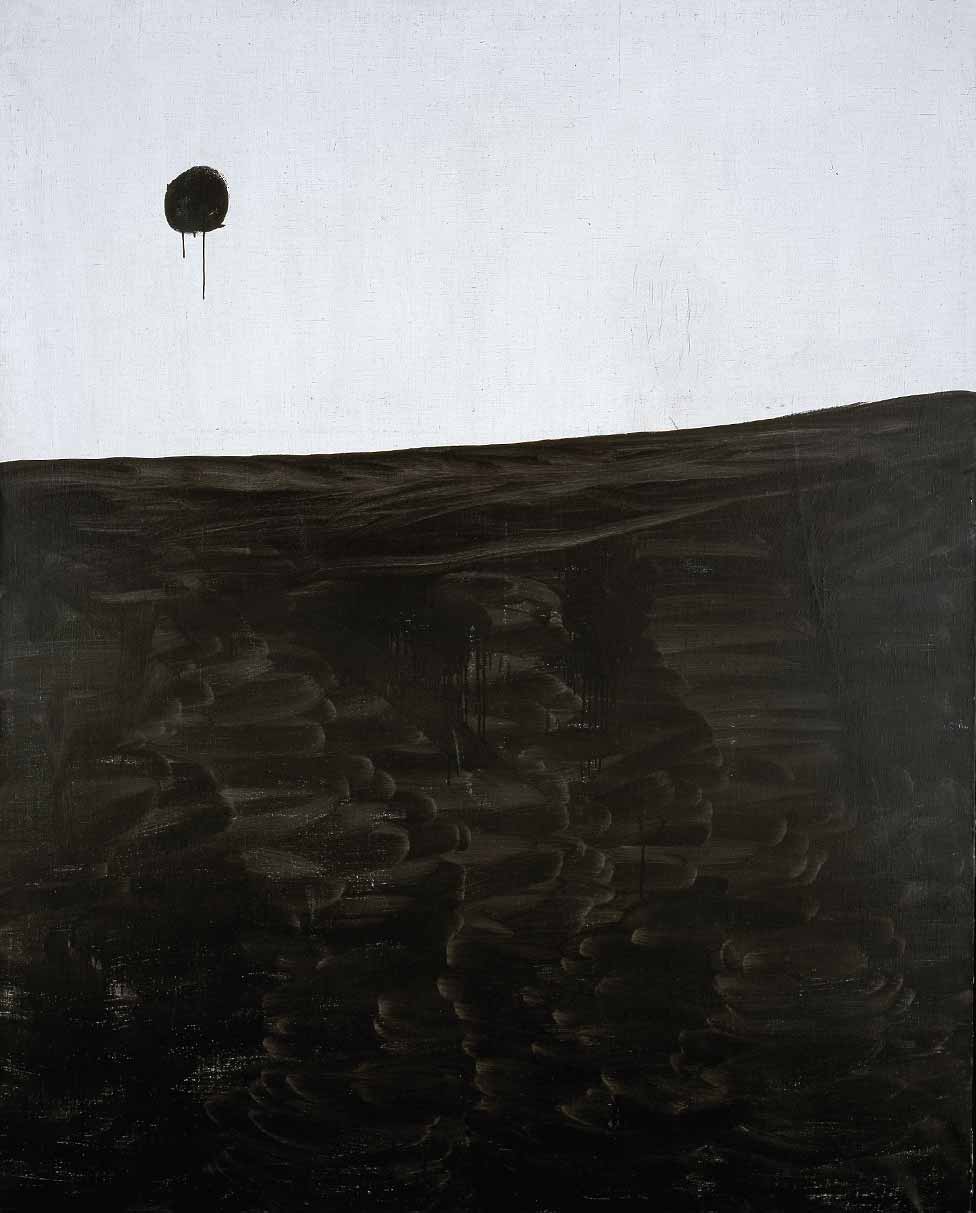

Monumental formats

Blue picture grounds [embody] pure painting that arises from the feeling of solitude and despair that incessantly persecutes me.

Joan Miró

Miró makes use of that blue that accompanied him from childhood to create monumental textured backgrounds. On it he placed individual dots and linear elements in red and black.

Wall or space?

Miró often painted large pictorial formats as triptychs or tripartite images. The artist thus placed them in a Christian tradition and emphasized their monumental nature. The large surface they cover on the wall suggest that for the viewer the real space recedes, thus opening up a new imaginary one.

All about the mural

Painting has since the cave age been in a state of decadence.

Joan Miró

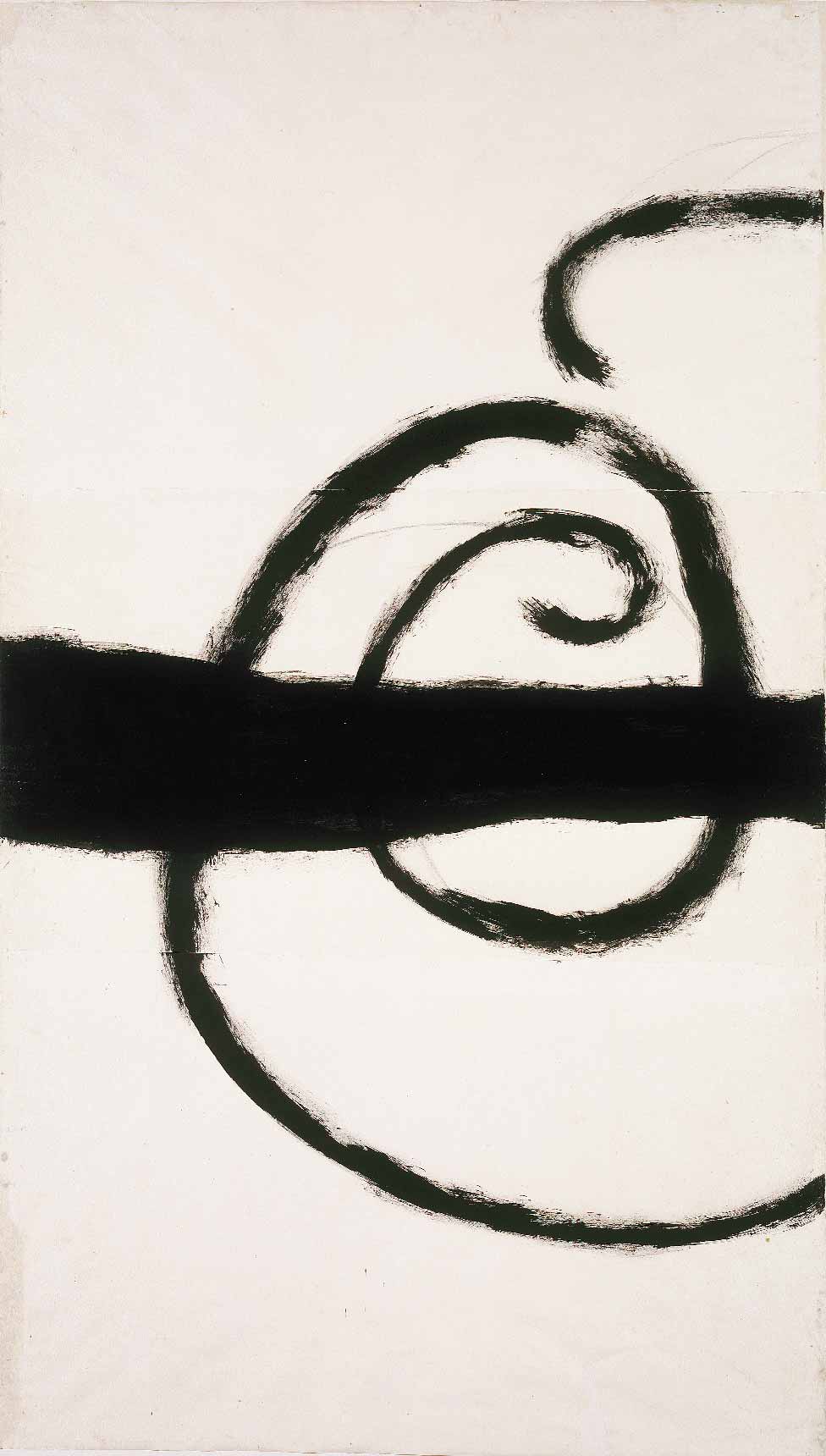

The wall as model

The wall is one of the oldest-ever media for images. Long before people developed the first written letters they covered cave walls with paintings, drawings and lines.

It’s the material that counts […]. It’s the material that defines everything.

Joan Miró

Experiments in ceramics

In the years 1955–59 Miró dedicated himself exclusively to ceramics, as part of which he created remarkable wall paintings with tiles. The “Wall of the Moon” and the almost 15-meter-long “Wall of the Sun” for the UNESCO HQ in Paris were the first of a series of large-format wall pieces for public spaces.

“The boy will go far”

Joan Miró never ever rested on his laurels. This shows a quote from the world famous, then 85-year-old artist in which he with a smile ironically calls himself a boy. In all phases of his life Miró created masterpieces because he took to new means on expression the way a duck takes to water. Embark on a voyage of discovery through the SCHIRN exhibition, where the large-format pieces and wall paintings will offer you a new angle on Miró’s art – over and above his famous, brightly colored dream-like paintings, which are admired the world over.

Personal hint

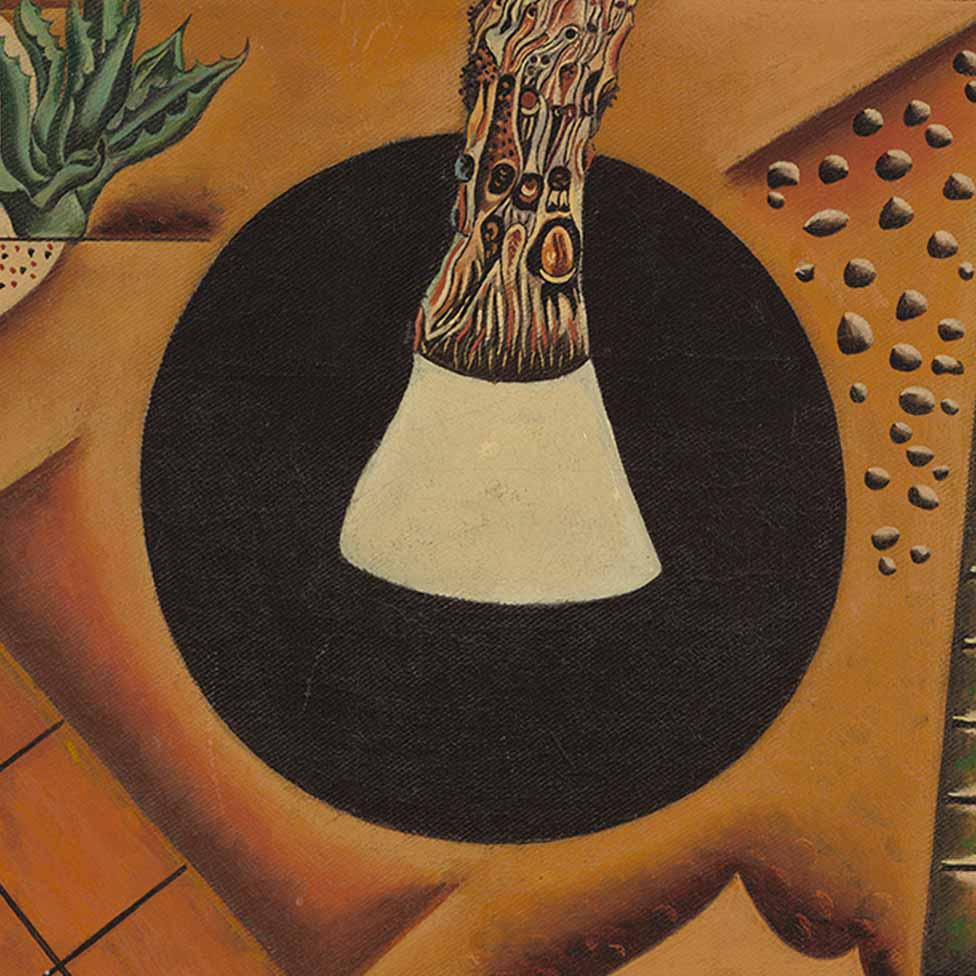

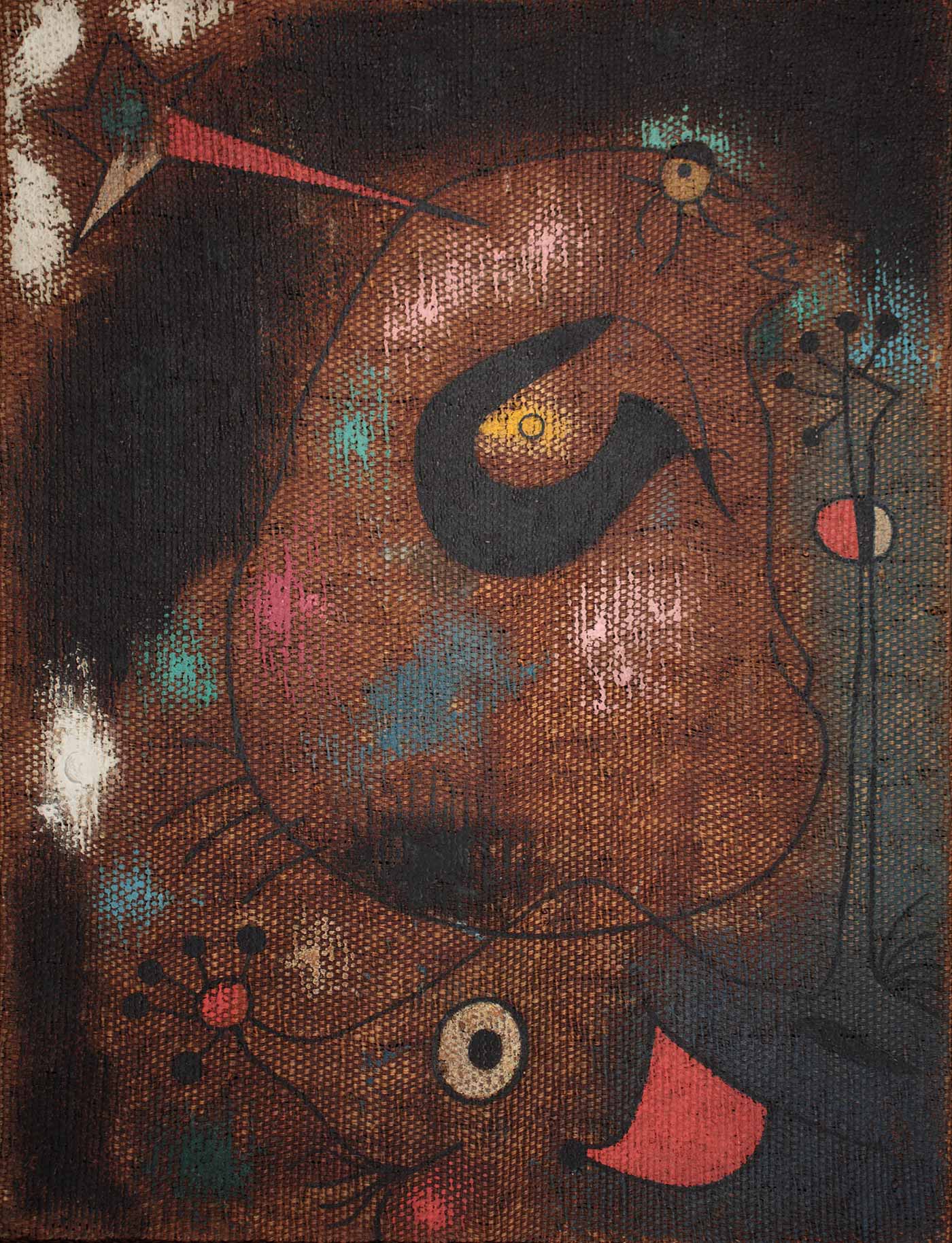

Which one can only glean from the original:

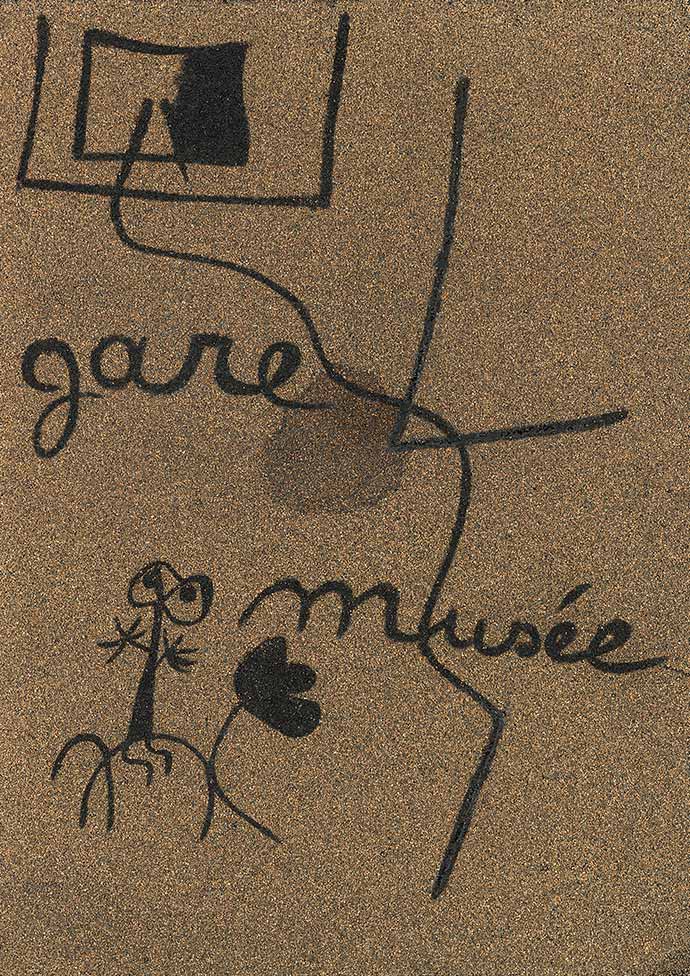

THE FASCINATION OF MATERIAL

Many of the details of Miró’s treatment of surfaces cannot be reproduced by digital means on-screen. Making it very worthwhile to view the materials as they appear in the originals – in the SCHIRN exhibition. This is especially true of the “Head of Georges Auric”, made in 1929.

The work was produced in a phase in the late 1920s and early 1930s when Miró was experimenting with unusual materials in order to overcome conventional painting. With his ceramic tile pictures he later sought to liberate art from the constraints of easels. Miró created a three-dimensional form of the traditional two-dimensional painting.