A conjurer of enigmatic paintings: The SCHIRN presents masterpieces by the surrealist René Magritte.

The painter René Magritte (1898–1967) was a conjurer of enigmatic paintings. In a concentrated solo exhibition devoted to the great Belgian Surrealist, the SCHIRN explores his relationship to the philosophical currents of his time. Magritte did not see himself as an artist, but rather as a thinking human being who conveyed his thoughts through his painting.

Throughout his life he sought to imbue painting with meaning equal to that of language. Driven by his curiosity and his affinities with some of the leading philosophers of his age, such as Michael Foucault, he created a remarkable body of work and developed an altered view of the world that is reflected in a unique combination of masterfully precise painting and conceptual processes. The exhibition sheds light on Magritte’s philosophical investigations in five chapters. His word pictures reflect his fundamental views on the relationship between language and visual imagery. Other essential pictorial formulas are concerned with legends and myths associated with the invention and definition of painting.

Stupidity of painters

Didier Ottinger, exhibition curator, comments: “There was a hierarchy stultified by centuries of philosophy that ranked composers and poets above painters, and words far above images. From Plato to Hegel, philosophy dismissed all figurative representation as confusion of the senses, considering poetry to be the most accomplished vector of the Spirit. René Magritte never put up with the expression “stupidity of painters” to which the Parisian Surrealists subscribed, relentlessly asserting the intellectual dignity of his art with his paintbrush, first against poets and later against philosophers. Magritte developed a kind of painting that postulated a relationship of equivalence between vision and thought, between the visual image and the word as the expression of thinking and knowing.”

René Magritte is one of the most important painters of the twentieth century. In contrast to the methods based on dream and automatism postulated by the Parisian Surrealists associated with André Breton, Magritte’s unparalleled visual language was grounded in the specifically Belgian manifestation of Surrealism, which called for the application of a dialectic method and scientific thinking. The expression “the stupidity of painters” that was commonly heard near the end of the nineteenth century, reflects the philosophical opinion that poetry ranked above painting and words above images.

Painting as a kind of equation

Magritte was unwilling to accept that premise. He defended the intellectual dignity of his art as long as he lived and sought to elevate his painting initially to the level of poetry and eventually to that of philosophy. Pursuing a quasi-scientific approach, the artist imbued his visual language with the objectivity of a vocabulary. His motifs–pipe, apple, melon, candle, curtain, flame, shadow, fragment, and hat, etc–recur in various different combinations and contexts in his paintings.

Magritte painted pictures whose meanings were intended to be universal. He viewed his painting as a kind of equation in which he ascribed to each work the solution to a “problem” in accordance with a dialectic principle. In La Condition humaine (The Human Condition) (1935), which is featured in the exhibition, Magritte focused on the problem of the window establishing links between inside and outside, the seen and the hidden, nature and culture, picture and landscape. The dialectical pairs that structure the world of his imagination appear in painting after painting: natural and artificial, interior and exterior, impulsive and rational.

The confrontation between text and image

Magritte’s first word pictures were produced about the time of his move from Brussels to France in 1927. The SCHIRN is presenting one version of his most famous painting from this group of works, La Trahison des images (Ceci n’est pas une pipe) (The Treachery of Images [This is not a Pipe]) (1927). The painting shows a pipe rendered in his typical precise style and beneath it the words: “This is not a pipe.” Magritte articulated his doubts about the amenability of reality to depiction in this contradictory confrontation between text and image and thus questioned the validity of perception in general.

In his witty and amusing theoretical treatise entitled Les Mots et les Images (Words and Images) (1929) consisting of 18 pairs of words and images published in the journal La Révolution Surrealiste, the painter questioned the complex relationships between the object, its name, and its visual representation. Magritte’s word paintings are his answer to the defamation of painting and an expression of his ambition to establish the equivalence of images and words as means of expressing thought processes and knowledge.

Justifying paintings on a scientific basis

Magritte’s interest in philosophical theories grew intensified beginning in the 1950s. He read the works of Martin Heidegger and Maurice Merleau-Ponty and sought personal contact with contemporary philosophers. His favorite discussion partners were the Heidegger expert Alphonse De Waelhens and Chaim Perelman, the famous philosopher of law. Magritte tested his ideas about painting in a dialogue with these thinkers and took advantage of every opportunity to question them. His interest in philosophy provided him with arguments for the complex character of his paintings and helped him justify his painting on a scientific basis.

He repeatedly turned his attention to ancient myths regarding the invention and essence of painting, such as Plato’s Allegory of the Cave and the painting competition between Zeuxis und Parrhasius as described by Pliny the Elder. The perfectly painted curtain, the motif with which Parrhasius eventually wins the contest in the fable, is one of the most frequently recurring motifs in Magritte’s paintings, such as Les Mémoires d’un saint (The Memoires of a Saint) (1960) or Le Beau Monde (The Beautiful World) (1962). They bear witness to the degree of reflection with which the artist ironized his own illusionistic brilliance and his ability to create realistic trompe-l’oeil images.

The recognition he deserved

Other persistently recurring constants are Magritte’s painted collages, including in particular those of fragmented bodies, as in Les Marches de l’été (The Marches of Summer) (1938). Here as well he harnesses his knowledge of ancient legends in service of his painterly contemplation of the themes of beauty, reality, and the creative process. Although Magritte’s relationships with philosophers were always friendly, they often talked at cross-purposes in terms of content. Neither De Waelhens nor Perelman granted him the noble philosophical status he demanded–for that he had to wait until his encounter with the great post-Structuralist Michel Foucault. It was he who finally granted Magritte the recognition he deserved at an advanced age and dedicated the famous essay entitled Ceci n’est pas une pipe to him posthumously in 1973.

NEW DIGITORIAL

The free digitorial provides you with background information about the key exhibition aspects

For desktop, tablet and mobile

Emerging from Anonymity

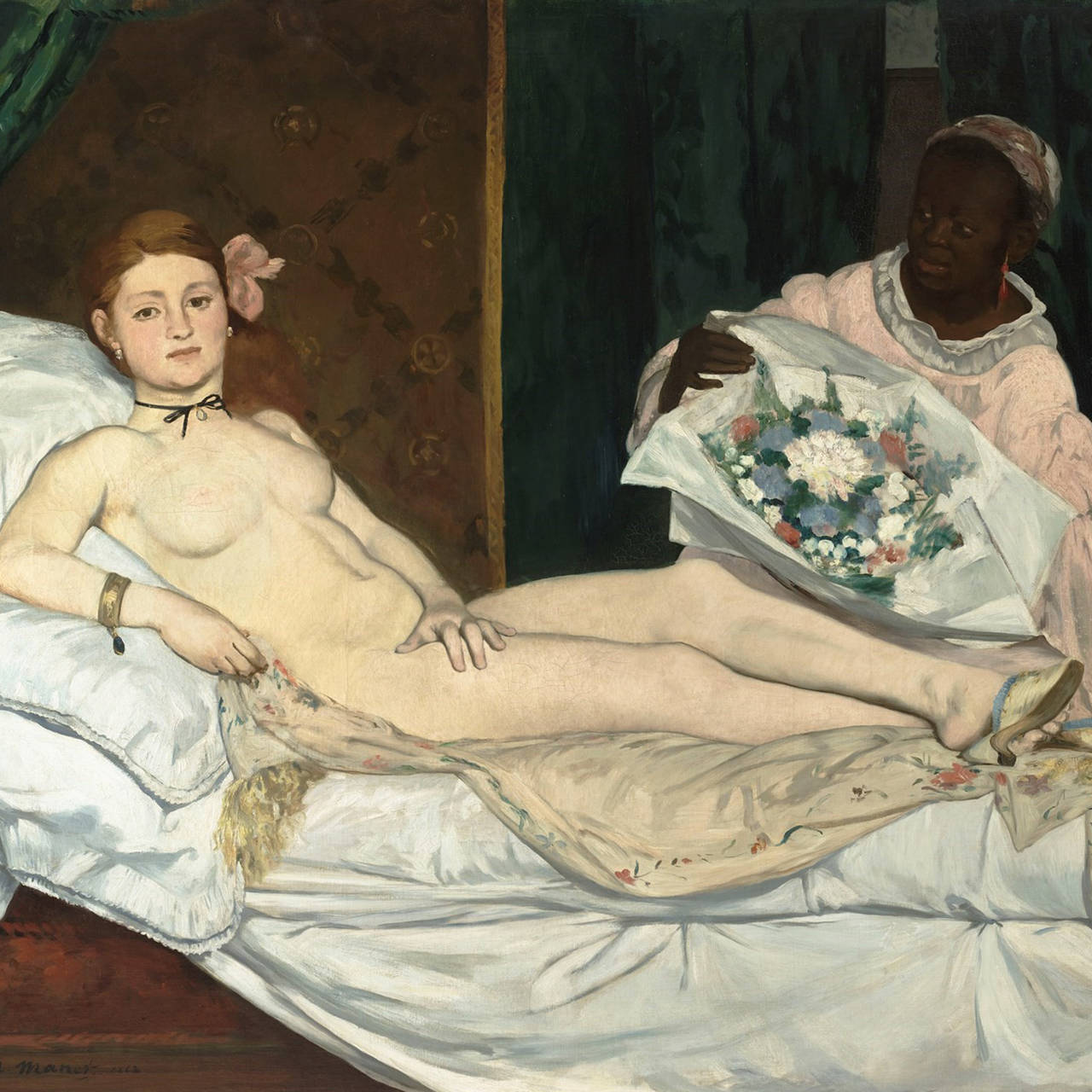

In 2019, an exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay put Black models in the spotlight of art (history). Dagara Dakin explains why it was so important to...

We, the trees

They are an indispensable part of the ecosystem and yet endangered the world over. The exhibition at Fondation Cartier in Paris is dedicated...

Out for a drink with Marcel Duchamp

Checkmate with Paris air and sparkling champagne. Our last summer drink with an artist who has turned everything upside down. Santé!

Surreal relationships: Three modernist artist couples

From the better half to the other self: how artist couples question traditional models of relationships.

The enemy of my enemy

From August 23 onwards, a unique project by artist Neïl Beloufa will transform the SCHIRN into a stage. Palais de Tokyo is currently hosting Beloufa's...

INTERVIEW. MICHEL HOUELLEBECQ

An umbrella, charm and a bowler hat

Inspired by the actions of the Parisian Surrealists, around the end of the 1920s a Surrealist group also developed in Brussels, centered around René...

Awaiting you at SCHIRN 2017

The SCHIRN 2017 exhibition year will be very varied with shows ranging from classical Modernist pieces to absolutely contemporary works.

Waiting for Magritte

A rare occurrence: Magritte is coming to Frankfurt on a large scale. Curator Martina Weinhart visited him in advance at the Centre Pompidou in Paris.

Around the world in comics

To mark the “Pioneers of the Comic Strip” exhibition, the SCHIRN MAG is travelling to ten comic stores on three continents.